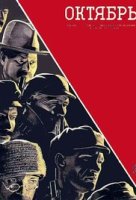

China Miéville, October: The story of the Russian Revolution (Verso 2017)

Before the meeting: The Book Group was recently immersed in post-revolutionary China with Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing. Someone remembered that this year is the centenary of the October Revolution and that China Miéville (whose The City and the City we read a while back) has written a book about it. In a nice piece of symmetry, given that according to the Western calendar the October Revolution happened in November, October is our book for September.

The book is tough going in some ways. The story of Russia from February to October 1917 is bewilderingly complex. A ‘Glossary of Personal Names’ at the back gives brief notes on 55 people who played significant roles. Maps of Petrograd and European Russia offer minimal help with the logistics. The multiplicity of political parties, and factions and committees within those parties, and the ever-shifting relationships between them, have a dizzying effect. Not to mention the fluid allegiances and political positions of the lead players.

But once you realise you don’t have to be on top of every detail, it’s an exhilarating ride. Miéville describes his intention in an introduction:

Though carefully researched – no event or spoken word described here is not recorded in the histories – this book does not attempt to be exhaustive, scholarly or specialist. It is, rather, a short introduction for those curious about an astonishing story, eager to be caught up in the revolution’s rhythms, Because here it is precisely as a story that I have tried to tell it.

He goes on:

The year 1917 was an epic, a concatenation of adventures, hopes, betrayals, unlikely coincidences, war and intrigue; of bravery and cowardice and foolishness, farce, derring-do, tragedy; of epochal ambition and change, of glaring lights, steel, shadows; of tracks and trains.

It would be hard to find a better description of the book than that.

It tells the story in 10 chapters: ‘The Prehistory of 1917’, then a chapter for each month from February to October, and finally ‘Epilogue: After October’. Inevitably, given that structure, there’s a lot of One Damned Thing After Another. Miéville’s chapter titles help to keep one’s bearings. For example, the central theme in Chapter 3, ‘March: “In So Far As”‘, is the playing out of the decision in March that the Soviet (the organisation representing workers, soldiers and peasants set up after the February Revolution) would not take power itself or be part of the Provisional Government, but would support the Provisional Government ‘in so far as’ (postol’ku-postol’ku) its actions met with the Soviet’s approval. The title of Chapter 4, ‘April: The Prodigal’, signals that we are to keep an eye on Lenin, as this who returns from exile in that month.

Miéville has a good eye for the colourful, telling or absurd moment. My favourite occurs in the most intense moments of October, when a group of officials who support the Provisional Government demand that a member of the Red Guard to let them pass or kill them, making them anti-Bolshevik martyrs. He tells them to go home or he’ll spank them.

And though his language is mostly, appropriately, functional, every now and then there’s something to delight. Alexander Kerensky addresses the troops in March, and is met with testeria. It took a moment, but I realised that a less gender-conscious writer might have said ‘hysteria’, and I had a new word in my vocabulary.

The book sent me back to Eisenstein’s 1928 film October (on YouTube here). What to a 2017 reader and film-viewer is history, was living memory to the film’s original audience. The book explicates some episodes. The episode of the Red Guard threatening to spank the officials is a good example: in the absence of dialogue (at least in the version I saw), repeated shots of the handsome young soldier calmly shaking his head ‘No’ would have reminded the 1928 audience of the famous line – for us, it does so only if you’re read it elsewhere. On the other hand, because many of the places that feature in the revolution were virtually unchanged in 1928 the film illustrates the book brilliantly. The role of women, which I suspected Miéville had retrieved for modern sensibilities, features prominently in the movie.

The book sent me back to Eisenstein’s 1928 film October (on YouTube here). What to a 2017 reader and film-viewer is history, was living memory to the film’s original audience. The book explicates some episodes. The episode of the Red Guard threatening to spank the officials is a good example: in the absence of dialogue (at least in the version I saw), repeated shots of the handsome young soldier calmly shaking his head ‘No’ would have reminded the 1928 audience of the famous line – for us, it does so only if you’re read it elsewhere. On the other hand, because many of the places that feature in the revolution were virtually unchanged in 1928 the film illustrates the book brilliantly. The role of women, which I suspected Miéville had retrieved for modern sensibilities, features prominently in the movie.

The main difference between the two is probably in the tone, especially in the endings. The movie ends with a sense of a triumphant beginning, the book with a lament for how terribly wrong it all went in the following years, and a muted hope that a just, unexploitative society might yet be possible, that the lessons of the Russian Revolution are yet to be learned.

The meeting: There were six of us, and though not everyone loved the book, it generated a terrific conversation.

One group member said that this is not a book to listen to as an audiobook: the stream of Russian names, the absence of the chapter-heading signposts, the impossibility of flicking back and forth in the text make it almost impossible to follow the story. A couple felt that the writing was pedestrian. We all engaged with the content: not so much ‘this is what a revolution looks like’ as ‘ this is how that one happened’. We lamented the fragmentation of society that makes mass actions like those in this book seem almost surreal, and the way technology has speeded up communication so that paradoxically there is less time for thought, for response, for organising.

Is violence necessary for major social change? Was Stalin inevitable? These questions were not answered, either by the book or by us.

On Eisenstein’s ‘October’; you know the saying about “when legend becomes fact, print the legend”. That was certainly true for Eisenstein. It turns out that he caused more damage to the Winter Palace during the filming of ‘October’ than was ever actually incurred during the actual October Revolution. In particular, the Winter Palace was only defended by a unit of military cadets. When the ‘Aurora’ sailed up the river, the ship put up a star shell to signal its arrival and for the assault on the palace to begin; the cadets took that as a sign that they had come under some sort of bombardment, and felt able to surrender with maximum honour and minimal loss of face.

But Eisenstein’s account looks far more exciting and paints his paymasters in a far more heroic light; so he filmed the legend, and it has stuck.

You concluded your review with the question, “Is violence necessary for major social change? Was Stalin inevitable? ” I’ve got the book in my TBR pile, and from what I’ve seen, I don’t think Miéville tries to answer that question either. A recent review I saw bracketed ‘October’ with Tariq Ali’s ‘The Dilemmas of Lenin’ which covers some of the same ground. I also have a copy of that in the TBR pile, and now I suppose I shall have to read both of them. Real Soon Now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t know that about the film causing more damage to the Winter Palace than the actual revolution, but it’s not surprising. I was surprised, though, when I watched the film recently, how little actual violence is shown in the storming of the Winter Palace. The emphasis is very much on the juxtaposition of the poorly clad revolutionaries and the sumptuousness of the palace. I was also surprised at how much of the stumbling and bickering is in the film.

Miéville does raise the question of what a successful revolution might look like in his epilogue, though not explicitly the question about violence. At least one person in our group read him as assuming (or at lest hoping) it was possible.

I guess I should add Tariq Ali’s book to my teetering TBR pile now … thanks for mentioning it

LikeLike

Your description of the hectic pace etc of this revolutionary period reminds me somewhat of Hilary MANTEL’s A Place of Greater Safety – about the early stages of the French Revolution through to The Terror.

LikeLike

That book was mentioned at the group, Jim. None of us had read it, but it was floated as a probable example of ‘good writing’ about revolution

LikeLike

I always enjoy reading your reading group reports Jonathan. I liked your comment about realising you don’t have to be on top of every detail. That’s a lesson I often have to re-learn. Oh, and I do love the word “testeria”. Nearly as good as “herstory”. I’ll have to add it to my lexicon.

My group met this week and we did The museum of modern love. We had a good discussion too.

LikeLike

Thanks Sue. I’ve since looked up testeria in a number of online places, and it seems that it’s been coined in a number of places, with a range of meanings.

My partner has enthused about The Museum of Modern Love.She read it back to back with a biography of Marina Abramovich, and said that enriched her reading of both books.

LikeLike

I’d like to read a biography of her, but I don’t think I’ll find the time. The documentary on this exhibition, which also tells much of her life as well, though, worked very well with the book. It’s available free on iView (but only until tomorrow!)

LikeLike

Pingback: The Book Group and Svetlana Alexievich’s Chernobyl Prayer | Me fail? I fly!