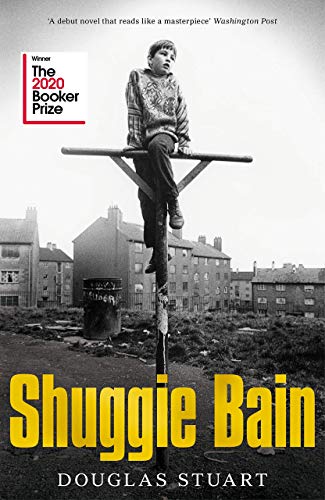

Douglas Stuart, Shuggie Bain (Picador 2020)

This is a Book Group book.

Before the meeting

Shuggie Bain is the story of a boy who grows up in poverty in Glasgow, the youngest of three children. His mother, Agnes, is an alcoholic who is brutally treated by her husband, Shuggie’s father, and then abandoned by him. Once a stunning beauty, she struggles to maintain appearances as she descends into increasingly desperate poverty, alienated from other women and sexually exploited, often violently, by men. From an early age, Shuggie takes on the burden of looking after her, protecting her and trying to make things better. The downward trend is reversed at times when Agnes joins AA, finds part-time employment and has a relationship with a decent man, but there is never any doubt about how her story will end, or that she will take Shuggie down with her. Through it all, Shuggie is singled out by adults and other children as different, not a proper boy – it’s a story of growing up gay.

The Wikipedia entry on Douglas Stuart gives an account of his childhood that could easily be a plot summary of the book. It’s surely no coincidence that ‘Shuggie’ rhymes with ‘Dougie’ (though maybe not in Australian pronunciation, if ‘Shug’ is short for ‘sugar’ as in The Color Purple), and the opening line of the acknowledgements refers to the author’s mother ‘and her struggle’. So the book presents itself as a fictionalised version of the author’s own childhood. As such it’s a valiant work of imagination, wrangling terrible experience into words. I admire it, I read it compulsively, I must have been moved by the horror because when I reached the book’s one moment of genuine tenderness I felt an extraordinary sense of a weight lifting from my mind, even though I knew it was only temporary. But …

… if I hadn’t been reading it for the book group, I would have stopped at page 37, where Agnes is beaten and raped by Big Shug. Really, do I need any more images of that sort lodged in my brain? I did read on, encouraged by the fact that the book won the Booker Prize in 2020, and I’m glad I did, but I found the insistence on the misery of Agnes and every other character in the book disturbing. I can explain what I mean by way of a tiny moment fairly early on. Agnes has regained consciousness after a night of drunkenness, destruction and violence:

Agnes wrapped her lips around the cold metal tap and gulped the fluoride-heavy water, panting and gasping like a thirsty dog.

(page 72)

She has been beaten up, raped, and shunned. She has done appalling things in her drunken state. Now, the tone of this sentence implies, she has reached such a state of degradation that she drinks directly from a tap, and not only that, but the water has been fluoridated! Where I come from, you don’t have to be subhuman to drink fluoridated water from a cold tap. It feels as if the narrator, if not the book itself, has lost perspective, and I lose faith. It could be that this sentence is a momentary false note. After all, as Randall Jarrell said, a novel is a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it. But my uneasy sense that perhaps this was a work of Misery Porn persisted for the rest of the book, even while I engaged intensely with the characters.

Between reading the book and the Book Group meeting: I took the book, and my unease about it, seriously enough to do some counterpoint reading – that is, to read writing that deals with similar material from different points of view. Interestingly enough, the other reading led me to a better appreciation of Shuggie Bain.

1. Jimmy Barnes’s memoir Working Class Boy (link to my blog post here). The early chapters tell of a childhood in a family and community in Glasgow, where alcohol-fuelled violence is as prevalent as in Shuggie’s. Young Jimmy could easily have been one of the boys who terrorised young Shuggie.

They are different kinds of book, of course. Jimmy Barnes can expect his readers to know him as a rock star, and to read the memoir as his back story. As he tells it, the young Jimmy was able to escape from the violence at home, and he went pretty wild on drugs and alcohol himself. Writing as a grandfather, he repents the errors of his youth and writes with generosity and forgiveness of his parents.

The narrator of Shuggy Bain doesn’t have that kind of safe distance from the events he describes. The novel has a visceral immediacy. The account of Agnes’s degradation is told from a point of view not far removed from Shuggie’s own, so the reader is aligned with the helpless child bystander. If the narrator has any distance at all, I imagine it’s that of an adult Shuggie who has escaped Glasgow, and looks back in horror at what he witnessed and endured.

2. Wendy McCarthy on the ABC’s Conversations podcast describes her own response when she saw her father lying drunk in the gutter.

This boy said to me, ‘You know your father’s a drunk,’ and I said, ‘Yep,’ and just kept walking. I learnt something then: I’m not going to carry his shame.

(The link is here. The quote is at 14 minutes and 20 seconds.)

Wendy McCarthy was already at high school when that happened, and had had time to build her inner resources. Shuggie Bain is a novel about a child who didn’t have that chance, and who was caught in the vortex of his mother’s shame.

3. Kit Kelen’s Book of Mother (blog post to come). On the face of it, this poetry collection has nothing in common with Shuggie Bain. Mostly, it plunges the reader into the experience of living with the poet’s mother’s dementia. The son/poet-narrator is an adult, but the poetry captures a kind of mental vertigo that has a lot in common with the way Shuggie is drawn into his mother’s struggles. Comparing the books, I realised Shuggie isn’t just a dreadfully abused child, but he’s also a person of extraordinary heroism. When everyone else abandons Agnes or – in the case of Shuggie’s siblings – escapes her destructive gravitational pull, Shuggie stays, loving her and trying to make things better for her, until the bitter end.

After the meeting: We met in person, all but three who were respectively on the road with a theatrical production, visiting New York for major family event, and home with non-Covid sick children. As usual we ate well and eclectically. Among other things we discussed the role of table tennis for one of us in the process of retiring from regular work; the joy for another at having no income to declare as he too is in the process of hanging up his tools; and our shared relief at having a government that isn’t just about slogans, announcements and cruelty.

The Chooser kicked off conversation about the book by saying that if he’s known what it was about he wouldn’t have picked it, but he’d trusted his wife’s recommendation. I think we were unanimously glad he had, as the book provoked animated, and at times intensely personal conversation.

Many, if not most, had had to overcome initial reluctance that ranged from my own borderline prissiness to not wanting to dredge up memories of a major alcohol-related disruption in his own life.

A number of the chaps said they’d had to take breaks from reading it – one said a dull work on (I think) the energy grid was a perfect palate cleanser. One of the night’s three absentees texted that it was like Hanya Yanigahara’s A Little Life ‘but without the gratuitous violence etc.’ Another absentee sent us a long text part way through the evening, and encapsulated the general sentiment in his summing up: ‘In the end it was really good but hard going. I’m glad it’s over but glad I finished.’

A number of things were identified as having won us over. We agreed that it’s beautifully written – one man said he kept stopping to reread sentences for the sheer pleasure. It feels real – you believe that the author has experienced something close to Shuggie’s life. The narrative has a strong forward drive: as readers we share Shuggie’s hope that Agnes will snap out of the downward spiral, or at least we want it desperately even though we know it’s futile – and we keep turning the pages. The moments of lightness, tenderness and spirited resistance (there are more than the one I remembered) are beacons in the gloom. And we feel strongly for all the characters: Shuggie’s older brother Leekie won more than one heart, and (for me at least) Eugene, the one man who genuinely loves Agnes, tore my heart out when he became the unintentional agent of her destruction.

It’s a terrific book. Next meeting’s Chooser has been urged to choose something cheerful.

I decided long ago that this one is not for me but it was still interesting to read your thoughts, and to entertain, however briefly, the possibility that you could change my mind.

I’ve taught children living this kind of life, and honestly, I struggled with my conflicted feelings about their parents. The faces of those children scroll across my eyes even as I type this. I don’t want to go there again, especially not when there are so many other books I could read. .

LikeLike

That experience of seeing the look on a child’s face is very like one described by someone last night, Lisa. It speaks to the power of the book and at the same time a reason people choose not to read it

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s hard to get the book club selection process right isn’t it? Some in my group are quietly grumbling at the light & easy books of which we’ve just had a run. Our next chooser has been prompted to go for something more challenging, so we’ll see where we end up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes. Our process used to be much more difficult when each book was decided on by consensus, and the consensus was often shaky. Now the rotating choosership means we’re all much more tolerant

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting about consensus being shaky Jonathan. I feel it has worked well for us. I would strongly resist rotating choosership because I fear I’d end up having to read some popular genre novels I just don’t want to give the time of day to. (I might, possibly, enjoy some, but they are low priority for how I really want to spend my time. One member, for example, loves classics but also greatly wants us to do Liane Moriarty. Am I a snob for not wanting to read her for reading group?)

Anyhow, I really enjoyed your write up of this. My reading group did it last year and it ended up being our top book of the year, closely followed by Nardi Simpson’s Song of the crocodile, which was closely followed by Girl, woman, other. It was a stellar year. I found my heart sinking many times as I read it, but I never resented it or felt like giving up because Shuggie was such a great character and I loved the writing. Leek and Eugene were characters who kept me going too. Some in the group did read it slowly because they had to put it down at times, but, surprisingly, no-one was sorry they’d read it. One did choose not to read it though – she’s been a mental health nurse and felt it would be triggering.

BTW I liked your discussion about Shuggie and Dougie. There might be something in that, ie it may be why he chose the name. However, in terms of the name, I thought the book tells us that its a short version of Hugh?

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you’re a snob, Sue, I’m one too. But the Chooser system means reading for the group can be a bit like catching a wave: it might fizzle, or dump you, or take you on a glorious ride, but whichever it is, it comes as a kind of gift. I love it.

Yes, Shuggie is a diminutive of Hugh, and maybe also refers to sugar, as in . Speaking of triggering, the book did that for one of our group, but on balance I think he was glad he read it.

LikeLike

I’m glad you like the chooser system Jonathan. The important thing is what works for a group isn’t it? I knew of one group that not only had the chooser system but the chooser then bought the book for the others. I think that didn’t work so well because some choosers chose cheap books rather than ones they necessarily thought a good bookgroup read. My friend started to become very disgruntled. It was, interstingly, a couples group, and went for decades until too many died. My friend is in her mid-80s. I love stories about bookgroups.

Our trigger-fearing member came to the meeting and I think felt that maybe she could have read it, but I think it’s probably good she didn’t.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the idea of making the Chooser buy books for everyone. Actually, that’s for values of ‘love’ that mean ‘hate’. But it wold probably led to lots of short books, always a blessing. I hope it wasn’t the burden of having to buy books that led to so many of them dying. And a Couples group! But who do they gossip abut the group to?

LikeLike

Haha Jonathan, who indeed. I guess instead of gossiping they debriefed with each other. “Did you hear what x said?” Etc.

And no I think age got them in the end! As I guess it might us! Hard as that is to believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person