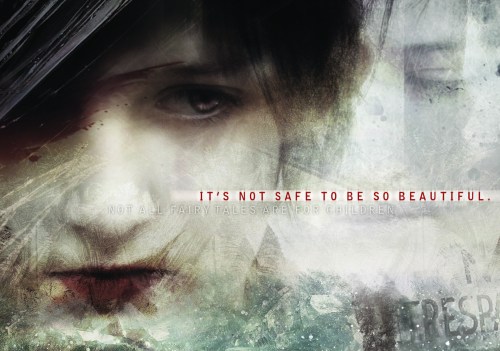

Re-enchantment, an interactive website exploring the history and meanings of seven of the best known fairy tales that has been a very long time coming, was launched yesterday and is now live on the ABC, at http://re-enchantment.abc.net.au/re-enchantment.html. I’ve had a quick look at the finished product, and though I have seen various beta versions, I was blown away. It’s gorgeous to look at, and the content is intriguing. Even the mechanics – working out which sparkly or moving images to click on and seeing where they take you – are great, allowing staid old folk like me a chance to share the thrill we’ve witnessed over young gamers’ shoulders. Some bits are slow to load on my computer, but that’s a minor irritation.

I’ve just programmed my TV to record the interstitial shorts being shown on the ABC over the next couple of weeks. In case you want to keep an eye out for them as well, and bearing in mind that the ABC may vary its schedule in response to teh next natural or political disaster, they’re:

Episode 1: Ever After (ABC1 Sunday 6 March, 4.30 pm)

Fairy tales, sometimes called wonder tales, have existed for thousands of years before they appeared as children’s stories. Why have they continued to appeal to adults across continents and across cultures?

Episode 2: If the Shoe Fits (ABC1 Sunday 6 March, 10.30 pm)

Cinderella is one of most popular fairy tales. Why has it survived for over a thousand years?

Episode 3: Wicked Stepmothers (ABC1 Friday 11 March, 10.55 pm)

Fairy tales are full of evil stepmothers and wicked witches. Why have these negative portrayals of women survived?

Episode 4: Princess Culture (ABC1 Sunday 13 March, 2.55 pm)

Are fairy tales responsible for our fantasies about princes and princesses?

Episode 5: Into the Woods (ABC1 Sunday 13 March, 10.30 pm)

Why is it that so many fairy tales take us into the forest?

Episode 6: Dark Emotions (ABC1 Friday 18 March, 10.55 pm)

Is it the dark side of fairy tales that makes them so valuable psychologically?

Episode 7: Beastly Husbands (ABC1 Sunday 20 March, 4.55 pm)

Animal bridegroom stories where a woman marries an animal husband exist in most cultures. Why have these stories been so popular?

Episode 8: The Forbidden Room (ABC1 Sunday 20 March, 10.30 pm)

The mystery beyond the door is a very familiar motif to modern audiences. What is the meaning of the forbidden room?

Episode 9: Fairy Tale Sex (ABC1 Friday 25 March, 10.55 pm)

Romance, princes and princesses are all associated with fairy stories, but what do they say about sex?

Episode 10: Re-imaginings (ABC1 Sunday 27 March, 10.30 pm)

Fairy stories aren’t relics of the past. They are constantly being re-interpreted in new ways by visual artists and writers.