Ivy Ireland, Tide (Flying Island Books 2024)

Tide may seem like a quietly generic title for a book, especially one that has a number of poems about the sea, but a laconic note on sources suggests a dark subtext:

The title of this book, Tide, and the title of the poem, ‘A Shallow Boat’, are both taken from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem ‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1832) with the necessary reverence.

I decided to read the Tennyson poem. I’m pretty sure I hadn’t read it before, but many of its lines (‘the mirror cracked from side to side’, ‘The curse is come upon me’) were familiar, probably from young Dorothy Hewett’s romanticism as recorded in her autobiography, Wild Card. Certainly Ivy Ireland’s compressed, science-related poems, with close observations of the real world, are not at all like Tennyson’s flowery, relentlessly rhyming lines. The word ‘tide’ occurs only once:

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

The note on sources, then, leads one to expect something death-related: the tide is metaphorical, bearing us inexorably away. The book only partly meets that expectation. There’s a lot of life here, and not much death.

The book is divided into four sections of unequal length named for tidal phases: ‘Ebb’, ‘Low’, ‘Flood’, and ‘High’. If I had to pick favourites, I’d say I enjoyed the poems in ‘Low’ most: in ‘Lake Poet’, in the context of the climate emergency (not explicitly named, but definitely there in my mind) the lake is less a thing of sublime beauty than a place that will hold the poet to account, as opposed to the city, where ‘nobody has to answer for anything; in ‘Cane Toad’, the poet and her young daughter encounter some teenagers on Valentine’s Day:

She asks me,

of all people,

if they are going to marry,

those beatified ones,

out decking each other in posies

in the quiet toilet paper aisle.

‘Killing Plovers’ is a yarn about family life that takes on a fable-like quality about humans’ relations to other animals; ‘The Birth of the Universe’ is a wonderful poem about a) the Big Bang and b) giving birth.

The section ‘Flood’ comprises six prose poems, including ‘I Am John Is Dead’, long enough to be called a short story, about a young woman’s encounter with a New Age guru in the outback, which accurately describes itself as ‘like a Jim Jarmusch film’.

Page 47* is the title page for the book’s final section, ‘High’. The section includes just one poem, ‘A Shallow Boat’, in which the narrator with one other person goes sailing off the Queensland coast. Since the note on sources mentions this poem, I looked at the Tennyson poem again, and found:

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Outside the isle a shallow boat

Beneath a willow lay afloat,

Below the carven stern she wrote,

The Lady of Shalott.

This is the boat on which the Lady of Shalott floated to her doom.

Happily, the speaker of Ivy Ireland’s sailing excursion survives, having had a very nice time, even if it is sometimes scary and perhaps humiliating as she feels her incompetence.

Here’s the first of the poem’s 12 parts, from page 48:

A Shallow Boat

1.

Out on the water,

wind shocks with volume.

Waves whip-crack me to sleep,

hustle me awake at all hours.

The boat screams in joyous bells

beyond twelve knots.

I lack words to remark on

the changeability of air and temper,

the tang on my tongue

as words are taken from my mouth

as sharp as the smack of cormorants

hitting water

in free-fall.

All I really want to say about this is that I love it. I have no desire to go sailing. I breathe a guilty sigh of relief when I realise that the Emerging Artist gets seasick very easily, so is unlikely to be urging me to do it. But I love it as evoked in this poem.

The poem is almost a sonnet. The first six lines describe the wind, the waves, the sounds of the boat. Then there’s a turn, and in the next five lines the poet tries and fails to articulate a response. Then there’s a three-line equivalent to a sonnet’s final couplet – rather than a witty encapsulation of what has gone before, here it’s the cormorants, ostensibly a metaphor for the poet’s speechlessness but actually just there, smacking the water.

Every verb, every adjective, every noun is carrying its share of the meaning-load, and the sound design is wonderful. The echoing Ws bind the lines together, with a little respite for Ts (‘temper’, ‘tang’, ‘tongue’, ‘taken’, and then ‘cormorants’) in lines 8 to 11. Back to W and then the Fs in the last line introduce a new, final sound.

The Tennysonian hints of doom may be realised in later parts of the poem, as in these chillingly succinct lines from part viii:

There's a point

where climate emergency,

once witnessed,

ticks over from

possible to inevitable;

anything else is inconceivable.

But that’s context rather than substance. The joy in this poem, as in the whole book, is in celebrating engagement with the natural world, vulnerable, dangerous, fragile, awesome, beautiful, breathtaking (sometimes literally). From section ix:

Orange shifts over the horizon, and here we are:

alive, while countless others are not.

Who am I to deserve daybreak. This happening here,

sea eagle fishing beside the boat,

sea turtle snorting to the surface. What's it for,

to be so honoured.

I wrote this blog post on land of the Gadigal and Wangal clans of the Eora Nation. I’m posting it on a day that has shifted from bright blue sky to heavy downpour within hours. From my window I can see wet gum leaves reflecting the afternoon sunlight as they have been witnessed by First nations peoples here for tens of thousands of years.

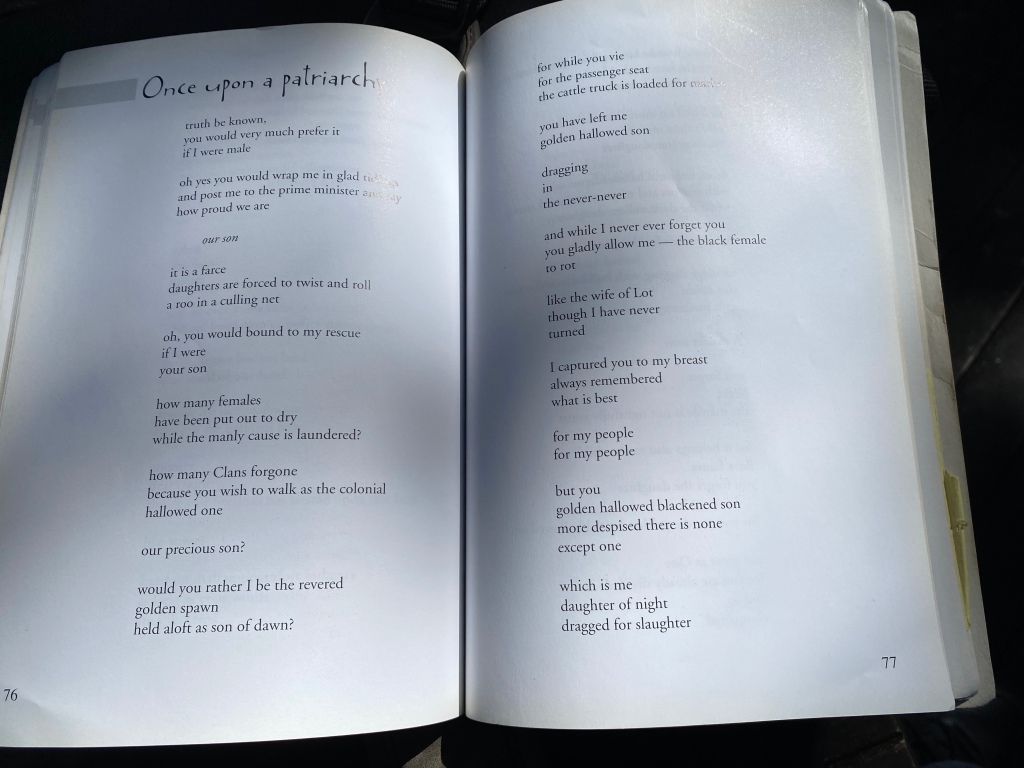

* My blogging practice for some time has been to focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age. A focus on just one page seems to me to be almost necessary with books of poetry, where the parts are so often greater than the whole. As Tide has fewer than 77 pages, so I’m focusing instead on my birth year, ’47.