Romaine Moreton, Post Me to the Prime Minister (jukurrpa books, 2004)

Romaine Moreton is Goenpul Yagera of Minjerribah (aka Stradbroke Island) and Bundjulung of northern New South Wales. She is a poet, spoken word performer, philosopher and filmmaker. A brief showreel from the transmedia work One Billion Beats (2016), which she co-wrote and co-directed with Alanna Valentine, gives a powerful glimpse of her stage and screen presence, as well as her incisive writing (link here). Also on Vimeo is a profound lecture she gave about that work (link here), which discusses the colonial gaze and dissects colonial cinematic representations of Indigenous people.

Post Me to the Prime Minister, a collection of poems published in 2004, 12 years before that formidable work, also deals with issues faced by First Nations people. As I was reading it, I kept wishing I could see Romaine Moreton perform them. I’ve just been told that she opened for Sweet Honey in the Rock at the Sydney Opera House on one of their visits to Australia, which makes complete sense. The short film she made with Erica Glynn, A Walk with Words: The Poetry of Romaine Moreton (2024), ends with her performing the book’s final poem, ‘I will surprise you by my will’ (you can rent or purchase the whole film at this link). The poem is in the film’s trailer:

we are here and we are many,

and we shall surprise you by our will,

we wll rise from this place where you expect

to keep us down,

and we shall surprise you by our will.

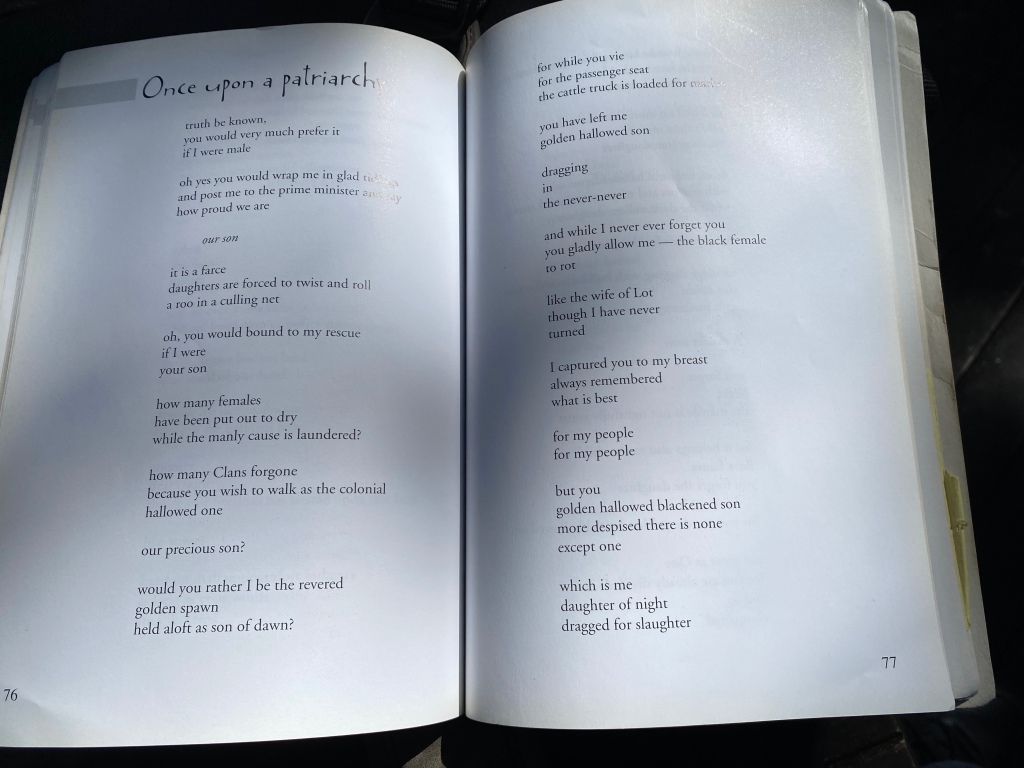

There are so many riches in this collection, but I’ll stick to my arbitrary practice of singling out page 77. It’s the second page of a long poem, ‘Once upon a patriarchy’. Here’s a pic of pages 76 and 77:

The book’s title comes from the poem’s opening lines:

truth be known,

you would very much prefer it

if I were male

oh yes you would wrap me in glad tidings

and post me to the prime minister and say

how proud we are

___ our son

Things have moved a long way since the moment in the 1972 movie Ningla A-Na when Indigenous women argued vehemently that sexism was a white women’s issue, that Indigenous women needed to support Indigenous men and not challenge their sexist behaviour. More than 30 years later, this poem’s speaker doesn’t have to be defensive about the ‘colonial gaze’; it’s not written with a non-Indigenous reader foremost in mind. The strength of First Nations communities no longer depends on papering over the cracks of lateral oppression.

It’s not easy to tell who ‘you’ is in this poem. At first it may be the speaker’s parents, or perhaps a part of the First Nations population that has a parent-like relationship to her. But it shifts, and by the start of page 77 it is a First Nations man, ‘our son‘, who is being addressed. He’s a man who wishes ‘to walk as the colonial / hallowed one’. I don’t think it’s too fanciful to see him as similar to the would-be assimilationist Tomahawk in Alexis Wright’s great novel Praiseworthy (2023), or perhaps as a member of Chelsea Watego’s ’emerging tribe’ of self-appointed leaders (see the essay ‘ambiguously Indigenous’ in Another Day in the Colony, also published in 2023).

for while you vie

for the passenger seat

the cattle truck is loaded for market

you have left me golden hallowed son

dragging

in

the never-never

This is beautifully complicated. There’s sibling rivalry – ‘golden hallowed son’ is a variant on ‘golden-haired boy’, the favoured sibling, favoured partly because he’s male. But it’s not just that. He has decided to be part of the action, be up front in the cattle truck, join in the extractive farming of the land. He’s not in the driver’s seat, not in charge of his own destiny, but has attached himself to the power. To reinforce the farm metaphor, the poem brings in the Australian colonial ‘classic’, Mrs Aeneas (Jeannie) Gunn’s We of the Never Never (1908). I haven’t read that book, but I’m pretty sure its account of Mangarayi and Yungman who were displaced by the Elsey cattle station, and worked on it, fits the tone of these lines – a place to be left dragging.

The next lines continue to reproach, and to remind the ‘son’ of the loyalty shown by Black women. (See the scene in Ningla A-Na mentioned above.)

and while I never ever forget you

you gladly allow me – the black female

to rot

like the wife of Lot

though I have never

turned

I captured you to my breast

always remembered

what is best

for my people

for my people

Whatever else is going on with the ‘son’ his maleness is key, as is the speaker’s femaleness. The reference to Lot’s wife (who looked back at the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19 and was turned into a pillar of salt as punishment) broadens the picture: women have always been punished. In this case, though, there’s not even the pretext of he having done something wrong.

If you weren’t noticing the music of the poem previously, you can’t help but hear it here. These lines, with the rhyming of ‘rot’ and ‘Lot’, introduce a new rhythm that builds, with the rhyme of ‘breast’ and rest’, to the lovely repetition of ‘for my people’. When performing some of her poems, Romaine Moreton moves from spoken word to song. These lines cry out for that treatment.

One of my favourite words in poetry is ‘but’. And here it comes:

but you

golden hallowed blackened son

more despised there is none

The ‘son’ is not just ‘golden hallowed’, but ‘golden hallowed blackened’: sitting in the passenger’s seat doesn’t make him immune from racism. ‘Blackened’ is an interesting word here: it signifies First Nations identity, but also colonial attitudes. He may think of himself as the golden son, but his Black identity will be imposed on him and he will be seen accordingly through a colonial lens: ‘none more despised’. That’s something that the man on the receiving end of racism would readily agree to. And then the killer lines:

except one

which is me

That’s not the end of the poem, it does move on interestingly, but it’s all I’m looking at here.