I originally posted the following to the original version of this blog on 22 April 2004. I’m resurrecting it nearly 20 years later because my book group is currently reading another Sebastian Barry novel.

Sebastian Barry, A Long Long Way (Viking 2005)

I missed the last meeting of my book group, where they discussed, among other things, Barack Obama’s Audacity of Hope and Stephen Carroll’s The Time We Have Taken. I was saved from the embarrassment of admitting that I hadn’t read either of them by an invitation I couldn’t refuse: to see Zack Snyder’s Watchmen with my sons on the giant iMax screen. But I arrived at last night’s meeting with a clear conscience. I had struggled with the first third or so of A Long Long Way.

There’s a huge field out there of First World War novels, and I know some people can’t get enough of them, but the déjà vu was a bit much for me: from Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That, which I read an awfully long time ago, to Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, they all tell the same monstrous story. The fact that the cover design of my library copy of A Long Long Way uses the same photograph as one of Pat Barker’s books only added to the turn-off. And then there was Sebastian Barry’s prose: not at all a transparent vehicle for the story, but calling attention to itself by its Irish musicality, asking to be read slowly, even aloud. Here’s a random paragraph from the early pages:

Willie Dunne’s father, in the privacy of his policeman’s quarters in Dublin Castle, was of the opinion that Redmond’s speech was the speech of a scoundrel. Willie’s father was in the Masons though he was a Catholic, and on top of that he was a member of the South Wicklow Lodge. It was King and Country he said a man should go and fight for, never thinking that his son Willie would go as soon as he did.

All that repetition and inversion and balance and general quirkiness is beautiful, but when you start reading a novel that’s written in such prose, on a subject you feel may have been done to death, you’re not necessarily enthusiastic.

Resistance proved futile. The subject, I confess, is huge enough to generate a potentially infinite number of novels, each with its own urgency and richness, its own take on things, its own ability to compel. The First World War may yet turn out to be the war to end wars if we can only learn its lessons. There’s a powerful story, well told here, in the situation of the Irish who fought for the King of England in Flanders while their compatriots were battling the forces of the same king in the streets of Dublin. Worse – and I trust completely that Sebastian Barry didn’t make this up – there were Irish recruits among the army units that fired on the Easter Uprising rebels in 1916. The novel tells the story of Willie Dunne, one of those recruits.

There was no controversy at the group. The book had touched us all. Someone said that books such as this were very important to counter the nationalistic garbage that comes at us in Australia as Anzac day approaches, obscuring the reality of modern wars. One guy arrived late, having read the wrong book, Birdsong by the wrong Sebastian, surname Faulks. Apart from giving rise to much merriment, this threw a different light on my déjà vu response: we would mention some detail from ‘our’ book, and he would exclaim, ‘That’s in this one too!’

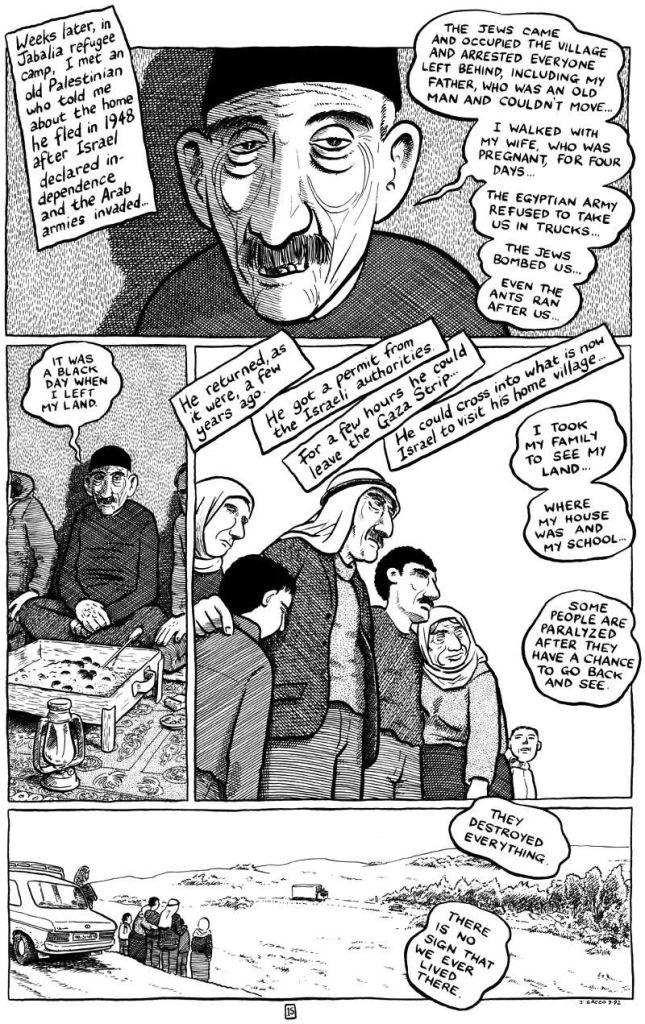

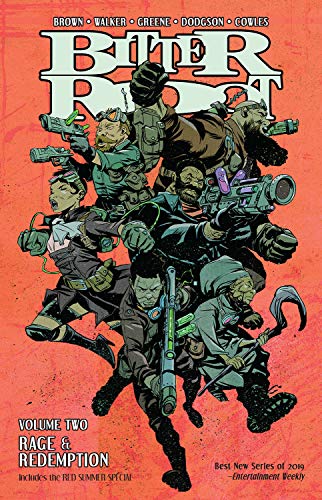

As an added extra, someone had recently rediscovered a cache of his childhood reading, and gave each of us a comic from the early 1960s. Here’s mine:

Different war, different propaganda.

Posted: Wed – April 22, 2009 at 08:01 AM