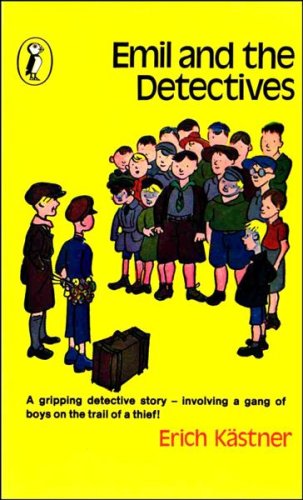

Erich Kästner and Walter Trier (illustrator), Emil and the Detectives (1929; translation by Eileen Hall 1959; Puffin 1984)

My virtual To-Be-Read pile includes innumerable children’s literature classics. Emil and the Detectives is one of them. I have somehow come to own a copy of it, and it seemed like the perfect read after the rigours of Edward Said’s On Late Style. I knew almost nothing about it. And of course, not being a children’s literature scholar, I still don’t know what its historical claim to fame is, but I did enjoy it, and had a complex enough response that I felt compelled to do a little background reading

First published in Germany in 1929, it evidently broke new ground by telling a tale set in recognisable current reality, mainly in Berlin, with a mainly realistic story. Emil, who lives with his mother in the tiny village of Neustadt, sets out by train to visit his grandmother and aunt and family in Berlin. His mother gives him the enormous sum of seven pounds (in Eileen Hall’s 1959 translation the money is British), one pound for spending money, the rest to help Grandma out. The money is stolen, and Emil has to catch the thief and retrieve the money. He is helped by an ever expanding gang of Berlin boys, and one girl. It’s not really a spoiler to tell you that they are successful.

The book was a delight to this 71 year old, and the note on my yellowing copy’s opening page is almost certainly accurate:

It is a book everyone reads with pleasure. Forward readers of eight could tackle it, while those in their early teens still enjoy it without wanting to disguise the fact.

The squabbling among the boys, their awe in the presence of the only girl, the presence of a kindly journalist named Mr Kästner, the acknowledgement to the smallest boy whose undramatic contribution to the project was nonetheless heroic, the attention paid throughout to tiny practical details, the evocation of the city of Berlin – nostalgic now but no doubt fresh and new then: so much to love.

The thing that sent me to Wikipedia was this: I became uneasy in the climactic scenes leading up to the villain’s capture. Some of this is described from his point of view:

Mr Grundeis found himself completely surrounded. He looked about in amazement, Boys swarmed round him, all laughing and talking among themselves, jostling each other, yet somehow always keeping up with him, Some of them stared at him so hard that he hardly knew where to look.

Then – whizz – a ball flew past his head. He did not like that, and tried to move more quickly; so did the boys, and he remained surrounded. Then he tried to take them by surprise by turning abruptly to go down a side street, but he could not get through the mass of children which seemed to stream across his path whichever way he turned.

And it goes on. Mr Grundeis threatens to call the police, but the boys call his bluff. And so on, until there’s a violent confrontation in a bank, and the boys convince the tellers and police (who do eventually turn up) that the man is indeed a thief. I can’t be the only one to be made uneasy by this scene of a cheerful mob of adolescent boys harassing a solitary man, especially in late 1920s Berlin. It’s possible that Mr Grundeis has some of the cultural markers for ‘Jew’. He is certainly described in more detail than any other character. He wears a bowler hat, and has ‘a long face, with a small black moustache and a lot of wrinkles around his mouth’. In addition, ‘His ears were thin and stuck out from his head.’

So I was uneasy. I did go to Wikipedia, where I learned that this is the only pre-1945 book by Kästner that wasn’t censored by the Nazis, so I’m reasonably assured that this isn’t deliberate anti-semitism. But I’m putting it out there as a question to people who know more about the history of this book than I do. Does this lovely book about youthful solidarity and power contain a coded version of the antisemitism that Hitler and the Nazis built on? Is it possible for the same story to make one think of the recent school students’ demonstrations for the environment, and in the same moment to remember that boy in Cabaret singing so sweetly, ‘The future belongs to me’? Or am I being hyper-vigilant in this age of assertive identity politics.

It’s too long since I read this book for me to remember, but the one you need to watch out for is Enid Blyton. She was notorious for the way all her bad characters were ‘swarthy’…

LikeLike

I remember that, Lisa. It was the only context that I knew for the word ‘swarthy’, and I’m relieved to report that I didn’t associate it with the dark-skinned people I knew – southern Europeans, Islanders, some East Asians. My Maltese brother-in-law recently referred to himself as ‘swarthy’, in the context of being singled out at airport security, so Enid Blyton lives!

LikeLike

Hmm! Published in 1929. A little too early for for the public anti-semitism soon to come during the 1930s I should think. The name Grundeis (Ground-Ice) and physical description (sounds more like Hitler than anyone remotely Jewish – that little moustache) – so I do not think – as you uneasily do here.

LikeLike

Yes, Jim. But I’m still left with a lingering unease. The Nazi stuff didn’t spring from nowhere. I don’t know if those hideous Nazi caricatures of Jews as rats were around, but the wrinkles around the mouth and sticking-out ears are a worry.

LikeLike

Cut and pasted from an email from my friend K, who knows her children’s literature:

Ah interesting concerns.

It’s been some time since I read Emil, and I am certainly NO expert on Erich K, but I do remember that the book was one of the very first ‘classics’ to feature adults (parents in particular) in any sort of prominent role. Wasn’t Emil’s mother a single parent too? So ahead of its time in a few ways. For so many years adults were conveniently offstage for most part, allowing young protagonists to get on with the action. In this one, that man Mr G is obviously pretty central to the action.

I have this idea that Kastner’s books were not only banned but actually burned by the Nazis, but I may be wrong about that …

I have to admit that the possibility of anti-semitism didn’t cross my mind. I have this other vague idea that villains are often dark haired with moustaches but there you go – probably just anti-semitism seeds growing in me! Basically wasn’t Mr G the one who stole the money? So he needs to be stopped! And how else are a group of ten-year-olds going to manage except by working as a ’team’ – AKA a gang. In light of all the current cultural and social awareness about gangs, I can see why you wonder what you do. I guess I didn’t see it as something to worry about myself, given the good-heartedness and adventure bent of the rest of the book. But I could be wrong!

Are you reading Charlotte’s Web now?

LikeLike

Thanks, K. Everything you say about the book gels with my reading, including you reference to our current awareness about gangs. What’s interesting, though, is that the passage I quote is from the only part of the book not told from Emil’s point of view. We are meant to feel Mr Grundeis’ discomfort as it grows to something like terror, so the adventure’s dark possibilities are there at an emotional level. But maybe I’m just sniffing for darkness.

LikeLike

Well it’s decades since I read this book but I remember loving it, particularly its exotic setting. Is the language also quite sophisticated? It was on my childhood bookshelf, which is unlikely to have included anything from a Nazi sympathiser, so I think your concerns are more modern than intrinsic to the book. Not that I’m dismissing the idea that racial (and gender) stereotypes sneak into all sorts of things.

LikeLike

I don’t think for a moment he was a Nazi sympathiser, Kathy. It’s the sneaky stereotype thing I was meaning. I’m pretty sure that my unease at that part of the book was an accurate response to the writing: suddenly the point of view changes from that of Emil to that of the thief, so we are meant to feel the awesome power of those children when they are organised and have a shared goal. The people, united, will never be defeated, kind of thing. But, mainly because it’s a children ‘s book (after all), the evidence against the man at that point is flimsy, and is subliminally based on his appearance (a bowler hat, a thin moustache and prominent ears!), my 21st century/post-Holocaust/Trump-era sensibility felt echoes of mob violence. Actually, the scene that did come to mind was the bit in the movie Shame where the Deborra-Lee Furness character is harassed by a gang of young boys.

LikeLiked by 1 person