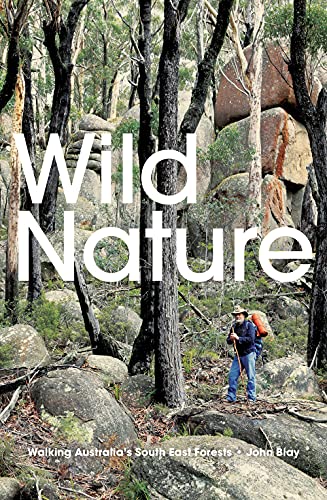

John Blay, Wild Nature (NewSouth 2020)

When I read Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees, in which sclerophyll forests might as well not exist, I yearned to read a book about the Australian bush. She who is known in this blog as the Emerging Artist had been urging me to read John Blay’s Wild Nature for more than a year. So, though I didn’t expect it to be an Australian extension of Wohlleben’s book, it pretty much leapt from the bookshelf into my waiting arms.

The book is made up of three major strands.

First, there’s the narrative through-line: the author’s account of an intrepid walk through Australia’s south-east forests, often following animal tracks and sometimes, memorably, forcing a way through thick vegetation by throwing his body against it. A woman named Jacqueline accompanies him on much of his journey. We never learn her second name and are left to deduce that she is his partner. The narrative is based closely on journals he kept on his walks.

Second, he gives a history of the ‘Forest Wars’, the bitter conflict between those who wanted to exploit the forests for timber and woodchips, and those who wanted to preserve it – with the Forestry Department, which once played a custodian role, at times coming down heavily – and, though Blay doesn’t ever say so, corruptly – against the ‘greenies’. This strand is the fruit of extensive work by Blay recording oral history from participants in both sides of the wars. Although his sympathies are clearly with the conservationists, he has warm, respectful relationships with people who have the industry’s interests at heart.

Third, he incorporates the fruits of research, including his broad botanical and ecological knowledge, and colonial and pre-settlement history. What Wohlleben calls the hidden life of trees is mentioned briefly, and at one stage Blay follows the path of early nineteenth-century shipwreck survivors, an episode explored in historian Mark McKenna’s From the Edge.

It’s a strange book. Too often, reading it is like going on a long bush walk with an enthusiastic guide who names every tree and bush you pass, except of course the reader can’t see them, so all we get is a list of botanical and geological names. I smiled ruefully when I read Blay’s comment on the shipwreck survivors’ account:

Without the on-ground knowledge of where they were from time to time, it would have made so little sense to those who seldom ventured into the outdoors that the long journey might as well have taken place on the moon.

(Page 263)

The slog is made worse by moments, all too frequent, that seem to have come straight from a journal and escaped the revising eye. This little passage is a good example:

All the tracks are treacherous bogs. Bandicoots have made trails in the wet earth. Across the heath, crimson bottlebrush and fairy fans glow brightest. Grevillea, bracelet honey-myrtle and banksia alike take the form of ground cover. A black snake suns itself on a sandstone pavement. The place is always full of surprises even as the landscape itself is surprising, it also has the potential to astonish.

(Page 111)

This list isn’t so bad – at least bottlebrush and grevillea are reasonably well known. But how did the triple tautology of that final sentence get past the copy editor?

So John Blay isn’t one of the great nature writers. But his enthusiasm for the south-east forest is infectious, and here are thrilling moments, of which two stand out for me.

In the first, he and Jacqueline come upon a grove of waratahs. Here is just part of the encounter:

In photographs the flowers seldom look as beautiful as they do in nature. They look too blue, too muted, grubby. Where is that red inner glow? How could they change like that? Photograph after photograph, they come back imperfect, in shades of dull murk, and each one makes me more determined to capture the flowers in their full crimson magnificence. In this heavily canopied forest the light changes subtly, as does the glow of the flowers. Their flashes can surround you like wildfires on a mountain. Any shards of sunlight cut through too brightly and wash out the subtleties. At times there is a halo miasma around the trees caused by the intensity of insect life attracted to the sweetness of the flowers; some insects are so tiny as to be visible only when the clouds of them are lit. One moth hovers, others strike at eccentric speeds, the native bees, wasps. All love the warmer morning air. As the heat increases, so do the insect numbers, until the dews dry and it gets hotter and just about all retire for a siesta.

(Page 167)

The other moment I want to mention takes the experience of reading the book onto a whole other level. On a spread toward the end there are two full-page maps of the area facing each other. One shows the forests of south-east Australia; the other the area burnt out by the bushfires of the 2019-20. The two areas are virtually the same. It’s like being hit over the head with a club: all of that wilderness we have been slogging through, the passionate object of John Blay’s attention, the bringer of aesthetic joy to Jacqueline, the terrain of the bitterly fought forest wars, all of it, has been ravaged by fire. As he tells us in the text, the heat from the fires has almost certainly damaged the complex underground web of fungus so necessary for the forest’s health. The scale of the disaster is close to unimaginable.

For all its faults, this book helps us to imagine it, helps to make the climate emergency viscerally real

I have just read Blay’s book on exploring for the old Bundian Way – from Twofold Bay to the high country of Mt Kosciuszko. And Mark McKenna’s Looking for Blackfella’s Point (2002 – updated 2012?) a history of the south coast/Yuin people. Both complement each other – and now about 100 pages in on Wild Nature. Not reading anywhere near as critically as you are JS – just delighting in being in that bushland and walking – having just spent some time down there on a road trip – with more planned from the high country south from Canberra towards year’s end…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you’re enjoying it, Jim. I discovered only in the last couple of pages that Wild Nature is the third book of a trilogy of sorts, of which the one on the Bundian Way is the first. My problem may be that I came in late, but the information is saved for the last couple of pages

LikeLike