This is my seventh post on books I took with me on my escape from Sydney’s winter, focusing as usual on page 76 (or page 47 when there is no 76): two very different bilingual books from Flying Island.

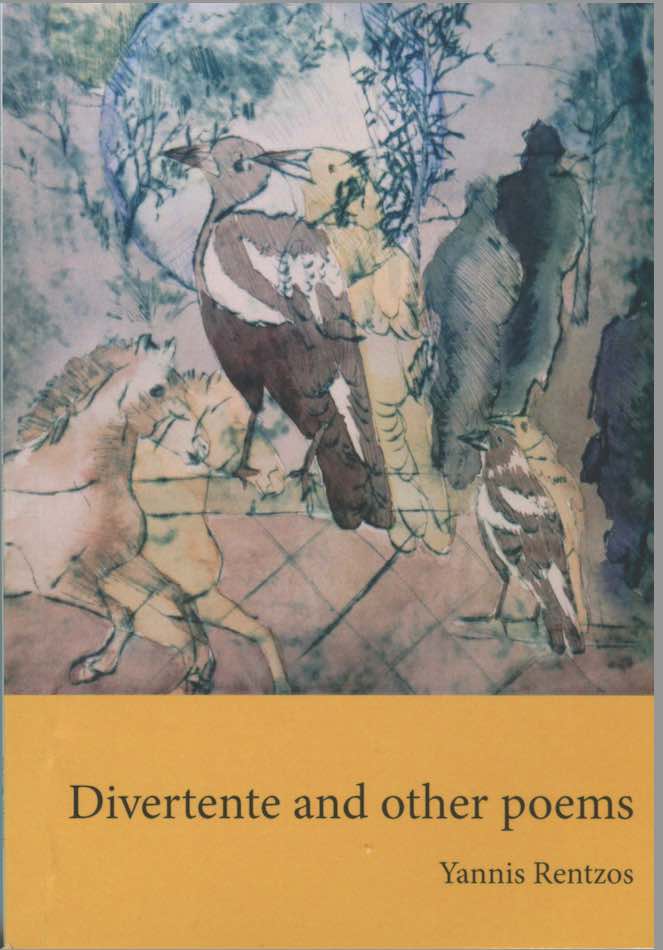

Yannis Rentzos, Divertente and other poems, translated by Anna Couani (Flying Island Books 2023)

Yannis Rentzos was born in Crete and has been living in Australia since 2006. His poems bear witness to his European roots as well as his antipodean present. The poetry is elliptical. I kept feeling that if I had been able to read the original Greek I would understand them better – not necessarily the evasive meaning, but perhaps something in the sound that is inevitably lost in translation.

For example, I particularly liked the poem ‘I know you are coming’, which seems to be about the death of a man, perhaps the poet’s father, whom he has ambivalent feelings about. Here are a couple of lines that suggest with wonderful economy that the man has spent time in prison, hint at violence, but remain opaque – in this way they are typical of much of the poetry:

In your first years on the outside a plate, a glass A suit hung unworn. The cops knew, they turned a blind eye

Were the plate and glass smashed, as suggested by mentions of violence in surrounding stanzas? Why was the suit unworn? Did the cops turn a blind eye to the broken stuff, or to the unworn suit? If the latter, does that mean the suit was stolen? So many unanswered questions. But the plate, the glass, the suit are there in the poem and in the man’s past, radiating meaning – it’s just that we readers don’t know what that meaning is.

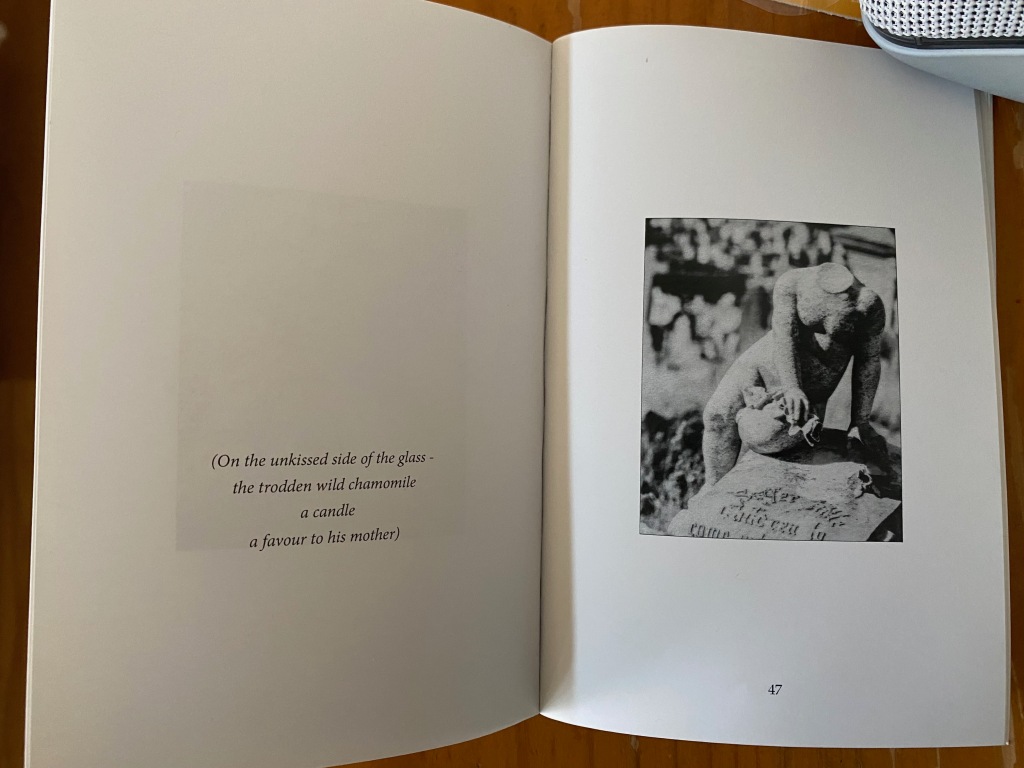

The final third or so of the book is devoted to a single sequence titled ‘Walk in Waverley’. Instead of Greek text on each right-hand page, there is a photo. In effect it’s a poetic-photo-essay on Sydney’s wonderful Waverley Cemetery.

Page 47 is on the second spread of the sequence, the first that includes text:

This gives you some idea of the way text and image relate to each other throughout. They don’t illustrate each other explicitly, but as the text – mostly a single line per page after this – evokes thoughts of death and transience, the images suggest a walk among the graves, disturbing the crows that live there. On this page, the text –

(On the unkissed side of the glass - the trodden wild chamomile a candle a favour to his mother)

– is a preamble to the walk that takes up the next ten spreads. It suggests a different style of grave from the one pictured – one with a glass-enclosed shrine. The man referred to in the fourth line maybe the person taking the walk through among the graves, starting at his mother’s grave. Perhaps these lines are a kind of dedication: ‘favour’ here meaning not so much as kindness as a token of affection or remembrance. You’ll notice that I say ‘perhaps’: nothing in this books is absolutely explicit.

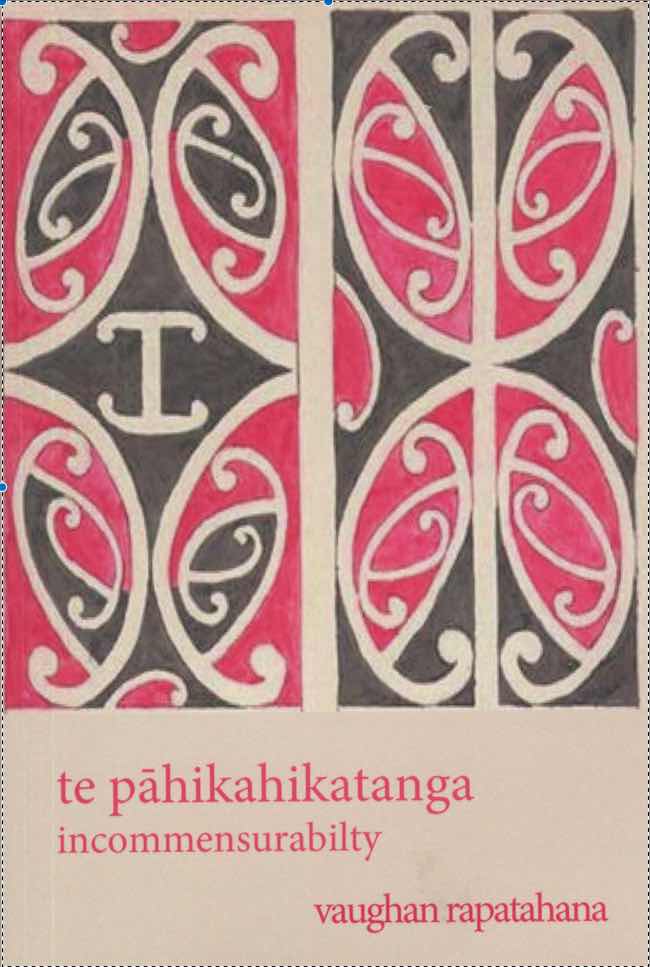

Vaughan Rapatahana, te pāhikahikatanga/ incommensurabilty (Flying Island Books 2023)

According to his author’s biog, Vaughan Rapatahana is one of the few World authors who consistently write in and are published in te reo Māori (the Māori language).

As well as a rich collection of poems rooted in Māori experience, this book includes a powerful essay on how important it is for Māori and other colonised peoples to learn and use their mother tongues.

The English language is one that historically and contemporaneously is all-too-often a deleterious influence on the languages of other cultures, in that its agents superimpose English with its inherent ‘cultural baggage’, on them. … The solution? To write in one’s indigenous language as much as practicable and to hope, to expect, that readers and listeners aspire to learn it too.

(Page 124–125)

Elsewhere:

I now write in my first language, the Māori language. Why? Because I want to fully express everything in my mind, in my heart, in my soul.

(Page 9)

I cannot express myself fully in another language. For example, the English language is crammed full of the subject matter and cultural customs of the lands of Britain. The words of that tongue are inappropriate.

The book is not just a bilingual book of poetry; it’s also a book about bilingualism. The incommensurability of its title refers to the impossibility of a ‘perfect’ translation. Anyone for whom the issues of translation matter will be interested. Likewise anyone interested in the long work of undoing the damage done by colonisation – to colonisers as well as colonised.

As a native speaker of the colonising language (with Irish and Scots Gaelic lost several generations ago), I’m reluctant to quote a whole poem, but here are a couple of lines from the English of ‘it is time for a big change’ on page 76:

there are many youths suiciding, ________________________-__ too many Māori youths there are many women as victims of domestic violence ___________________________ too many Māori women there is the ongoing issue of racism also, __________________________ remember Christchurch.

And the original te reo Māori:

ko nui ngā rangatahi e mate whakamomori; ___________ he nui rawa atu ngā rangatahi Mãori ko nui ngā wāhine ki ngā patunga o te whakarekereke ā-whare; ___________ he nui rawa atu ngā wāhine Māori ko te take moroki o aukati iwi hoki; ___________ e mahara Õtautahi.

You don’t have to know much Māori language to immediately see some things lost in translation: in Māori, the lines mostly rhyme; in Māori, the second and fourth lines can end with the word ‘Māori’, whereas in English, the word is in a less emphatic position; and where the English translation has ‘Christchurch’, the Māori original has ‘Õtautahi’. The first and second of these differences are about the music of the poem. The third is a small illustration of the principles I quoted earlier: the English name inevitably carries connotations of England, of the Englsh Christian tradition; the Māori name makes it that much easier to remember that the victims of that mass shooting were Muslim.

I’m grateful to Flying Islands Books for my copies of Divertente and other poems and te pāhikahikatanga/ incommensurabilty.