Patti Smith, Woolgathering (©1992, Bloomsbury 2012)

I’m coming late to Patti Smith. I know that her memoir Just Kids is much loved, and I know she partnered with Robert Mapplethorpe. (I have seen a major exhibition of his photos, including a curtained space with an explicit content warning in which nevertheless punters were vocally shocked). Wikipedia informs me that she is a singer-songwriter, poet, painter and photographer. I believe she was big in punk. Her only performance I have seen is her brilliant rendition of ‘A Hard Rain’ at Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize ceremony. (If you haven’t seen that, do watch it on YouTube, especially the absolutely disarming moment at about the 2 minute mark.)

This huge absence from my inner cultural landscape has now been slightly remedied, thanks to a well-judged Christmas gift.

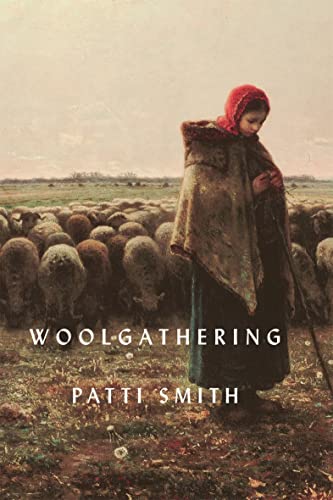

Woolgathering was first published in 1992 as number 45 in a series of tiny books – 3 by 4 inches (roughly 7.6 by 10 centimetres). That’s even smaller than the Flying Island Pocket Poets books, and only slightly bigger than the titles in Maurice Sendak’s Nutshell Library. It contained 15 prose poems and a healthy scattering of photographs, mostly taken by the author or featuring her or her family. It was reissued in 2011, expanded to 5 by 7 inches (12 by 19 centimetres), with a new introduction and four extra poems.

In her introductory note to the 2011 edition (which is what I have in my hand), Patti Smith says that the book was commissioned when she was living with her husband and two school-age children on the outskirts of Detroit, and experiencing ‘a terrible and inexpressible melancholy’:

Everything contained in this little book is true, and written just like it was. The writing of it drew me from my strange torpor, and I hope that in some measure it will fill the reader with a vague and curious joy.

I don’t know that it does that for me, but it’s a lovely book – to look at, to hold, to read and to reread. There are glimpses of her childhood, including the story of her marble collection, her caring for her often ill little sister, her relationships with parents and grandparents, and wonderful lines like this from ‘Barndance’:

The mind of a child is like a kiss on the forehead – open and disinterested. It turns as the ballerina turns, atop a party cake with frosted tiers, poisonous and sweet.

I read it as elliptical, discontinuous, even cryptic story of how she came to be a writer and artist. The first poem. ‘A Bidding’, begins, ‘I always imagined I would write a book, if only a small one’. And the next to last poem, having described a dream in which, while her siblings ‘sat watching in wordless admiration’, she ‘lay suspended a few feet from the ground’. She is almost tempted to try the feat in real life:

But my writing desk awaits , my open journal, my quills, inks, and here are precious words to grind. So I leave myself to wonder and begin, for I always imagined I would one day write a book.

Writing is a realistic alternative to flying.

Page 47* occurs in the middle of ‘Two Worlds’, one of the poems added in 2011. At first glance, it makes Patti Smith’s claim that everything in the book is true look a bit, um, disingenuous. It starts out like a realistic narrative with the poet watching scenes from Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (in which the main characters move through mirrors from the ordinary world to Hades), and morphs into a dream narrative. If it’s true, it’s in the way that dreams are true (as in Bob Dylan’s ‘The Gates of Eden’, ‘Sometimes I think there are no words but these to say what’s true.’) She is dressed like a poet from the movie, except that his shirt is spattered with blood – then she realises that her shirt is also stained, with ‘the deep red juice of kidney beans’, and soon she is actually bleeding. She wanders from the movie’s Café des Poètes to a series of other cafes that I’m guessing would be recognisable to US readers in the 1990s.

Here’s most of page 47:

I ordered another Pernod and water, but what I really wanted was to lie down. I lost a lot of blood and some had dripped on the page of my journal. The tears of Pollock, I explained to the waiter. The tears of Pollock I scrawled across the page. The drips multiplied forming a fence of slim jagged poles. The lines I had written multiplied as well. I could not tame them and my entire station was noticeably vibrating, as if teeming with newborn caterpillars. Quickly I drained my glass and motioned for another. I tried to focus on a portrait behind the brass cash register. Flemish fifteenth-century. I had seen it somewhere before, perhaps in the hall of a local guild. The sight of it produced a shudder and then a curious rush of warmth. It was her head covering. A fragile habit framing her face like the folding wings of a large diaphanous moth.

This makes me think that the whole poem is a kind of surreal ars poetica: an account of how she sees her own writing. I read ‘Pollock’ as referring to Jackson Pollock: where he dripped paint onto the canvas (and when I first typed that there was a typo, so he dripped pain), she lets her blood drip onto the page, and then scrawls over it. You probably don’t have to be an Australian of a certain age to have ‘fence of slim jagged poles’ bring to mind Pollock’s Blue Poles, whose purchase once outraged our philistine newspapers. But the dripping of raw pain onto the page isn’t enough: beyond the effects of alcohol and the brass cash register (am I over-reading to see this as a dream symbol of the commodification of art?), she struggles to focus on the stillness of a fifteenth century painting in which the other-worldliness of a moth embraces a woman’s face.

That image turns up again in a later poem, ‘Flying’, in a non-dream context but in almost exactly the same words:

Above my desk is a small portrait – Flemish, fifteenth century. It never fails, when I gaze upon it, to produce a shudder, followed by a ciurious rush of warmth, recognition. Perhaps it is the serenity of the expression or perhaps the head-covering – a fragile habit framing the face like the folding wings of a large, diaphanous moth.

And facing page features a photo of that face and its ‘fragile habit’ on her wall. (A quick web search identifies it as Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait_of_a_Lady.)

But ‘Two Worlds’ moves on – the Flemish portrait has been just a glimpse of quietness, perhaps something to aspire to. ‘I dreamed of being a painter,’ she writes, ‘but I let the image slide … while I bounded from temple to junkyard in pursuit of the word.’

This was Patti Smith in the years between punk stardom and her current status as grande icon, delving into memories, dreams and other people’s art to find her bearings, and rekindle in herself ‘a vague and curious joy’. Not bad!

I wrote this blog post on land of the Gadigal and Wangal clans of the Eora Nation. The heat is beating down, and the lizards are loving it.

* My blogging practice is focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age. A focus on just one page seems to work well with books of poetry, where the parts are so often greater than the whole. As Woolgatherers has fewer than 77 pages, I’ve focused instead on my birth year, ’47.