Eileen Chong, We Speak of Flowers (UQP 2025)

The author’s note at the start of this book begins:

We Speak of Flowers is a book-length poem in 101 fragments that can be read in any order. Each reading will construct the poem anew, and the shifting juxtapositions will give rise to innumerable permutations of the poem.

Considered as a book-length poem, the book is an elegy for the poet’s beloved grandmother. It also deals with other losses, especially those that come with being a member of the Chinese diaspora (and within that, of Hakka, Hokkien and Peranakan heritage). The dedication reads, ‘A poem for my ancestors’. But this isn’t a book with tunnel vision: there are Covid poems, childhood recollections, observations of life in Sydney, travels, meditations on artworks, and – as you expect if you’ve read any of Eileen Chong’s previous five collections – plenty of food. Images from Buddhist funerary rituals recur, and the clicking of mah jong tiles is heard more than once.

The author’s note goes on to explain that in Buddhist belief, the soul of a person who has died is reborn after 100 days, so the hundredth day ‘marks the end of the formal process of grieving the dead’. The 101st poem/fragment marks the moment of the soul’s reincarnation. The end is also a beginning. The invitation to read in any order implies that the grieving can begin and end with any one of the 101 fragments. Contrary to popular oversimplifications of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross‘s thinking, grieving is not a linear process. At the Gleebooks launch earlier this year, Eileen described the book as a choose-your-own-grief-adventure.

This sets up us for a tremendously complex – and engrossing – reading experience. I’ll limit this blog post to beginnings and endings.

In the book’s order, Fragment 1 consists of just two lines spaced widely apart on the page: ‘a singular, cracked voice // words matter, can still rise –’. In context this is the moment when a person caught in the intensity of immediate bereavement realises that they can still speak/write, and so the process of grieving can begin. It’s a perfect place for the larger poem to start. Fragment 101 begins, ‘And what did you leave me / in the end?’ I won’t quote the rest of it, just say that it brings the sequence to a perfect, heartbreaking end.

Though I found Eileen’s order very satisfying, I obediently ran the numbers 1 to 101 through a randomising program, and followed the resulting order for my second and subsequent readings.

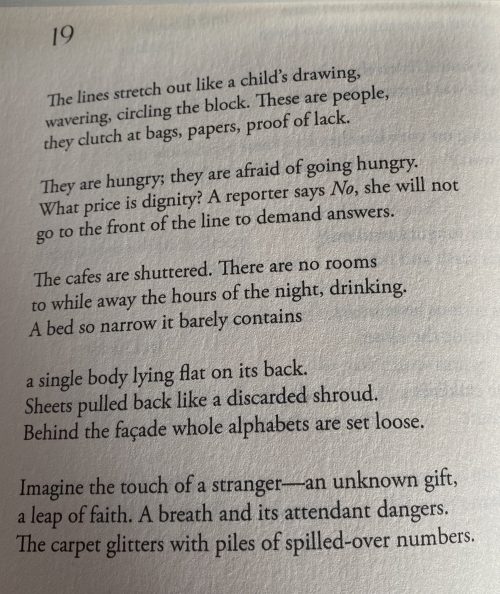

In this order, the larger poem begins with Fragment 19:

The poem consists of five three-line stanzas (triplets), a form this poet uses often. And as in many of her poems, there are some brilliant line breaks. One of several Covid poems, it captures a moment in our shared history. Beginning with a striking image of queues – for Centrelink, perhaps, or at a testing station – it goes on to evoke the loneliness, underlying dread and obsession with statistics that characterised lockdown days for many of us. I love this:

Imagine the touch of a stranger – an unknown gift, a leap of faith. A breath and its attendant dangers.

What oft was thought but ne’er so well expressed!

The fragment works brilliantly as the beginning of the larger poem. We learn later that the poet’s grandmother died when Covid restrictions were in place, and the poet and her Sydney-based parents weren’t unable to attend the Singapore funeral. So this poem establishes the setting for the main story. And there’s something else:

Sheets pulled back like a discarded shroud.

The image suggests a resurrection – that waking and getting out of bed, perhaps after an illness, is to have avoided death. But it also reminds us that not everyone has avoided it, foreshadowing the overarching theme of bereavement.

In my ordering the poet’s grandmother doesn’t appear until the third poem (Fragment 72), where she is very much alive at the mah jong table:

She pulls a tile and runs her thumb

along its underside, over its carved

indentations.

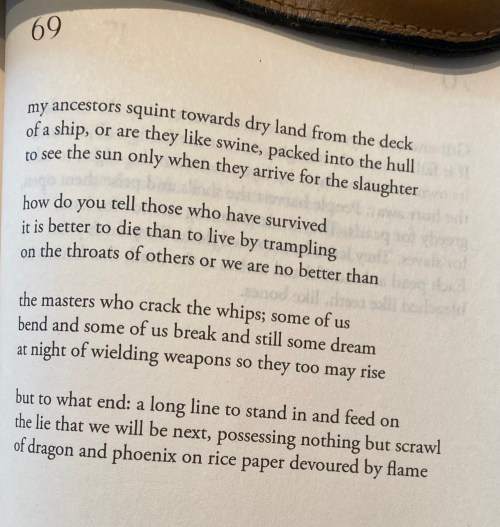

My randomised sequence ends with Fragment 69:

This is one of Eileen’s many poems exploring her family history and heritage. As often happens with these poems, I find myself thinking about my own very different heritage, but with a powerful sense of what is in common. When I blogged about her ‘Burning Rice’ (here), for instance, I brooded on the role of sugar in my life as the son of a sugar farmer. My forebears came to this country, some ‘squinting towards dry land from the deck / of a ship’, some as convicts ‘packed into the hull’. I guess that’s a way of saying that while the poem has specific historical references (about which I am vague), it somehow – as good poems do – makes a bridge to other, different experiences. This isn’t closed-off identity poetry. The ethical questions it poses aren’t just for people of Hokkien heritage.

I keep wanting the first line of the second triplet to be, ‘How dare you tell …’ That is, I want the lines to challenge anyone who passes judgment on survivors. But the actual words, ‘How do you tell …’, appear to endorse the stark ethical principle that it is better to die than to live by oppressing other people. Lines 4 to 7 ask how to communicate that principle to people who have made the choice to live in those circumstances. The question is left hanging and the poem moves on: in response to oppression, there are just three options: to bend, to break or to plot rebellion. The final triplet arrives at what is surely a doctrine of despair: no matter what we do we all end up dead. The dragon and the phoenix, traditionally paired in Chinese art and literature to represent harmony and prosperity, are possessed only as scrawled images on paper, and that paper will burn in a funeral ceremony.

How does this fragment function as the final moment in this longer poem?

Astonishingly well, as it turns out. For one thing, the image of standing in line occurs in both first and last poems. In Fragment 19, people line up around the block clutching at ‘bags, papers, proof of lack’, hoping for something. In Fragment 69, standing in line becomes a metaphor for a doomed aspirational life. We will never reach the front of the queue – it’s a ‘lie that we will be next’ – and what we possess is ‘nothing but scrawl’, paper ideals that will be destroyed at the funeral.

This fragment doesn’t end the sequence with the notion of rebirth or transcendence, but with resignation to the finality of death. The ship has reached its harbour. The funerary papers have been burned. There’s nothing left but profound sorrow.

At the launch, Eileen said, ‘I’m really a cheerful person.’ And I don’t want this blog post give the impression that We Speak of Flowers is a gloomy book. On the contrary, it deals with grief, it refuses to idealise or prettify its subject, but it’s still full of colour and light and the magic of language. Maybe I can leave you with the final couplet of Fragment 34 – which in my randomised order is Nº 78, the number that I usually blog about:

death in the afternoon

wild plants still flower

I wrote this blog post on land of the Gadigal and Wangal clans of the Eora Nation, where the earth’s processes are asserting themselves in heavy downpours followed by brilliant blue skies. I acknowledge the hundred of generations of past Elders, and present Elders, of both countries, never ceded.