Each December we – that is, me and the Emerging Artist formerly known as the Art Student – compile a list of our favourite books and films of the year. We’ve been caught this year with minimal internet coverage (and maximal sun, sand, beach, bush and rain, especially rain) so we’re running a bit late.

Three movies made both our top five lists:

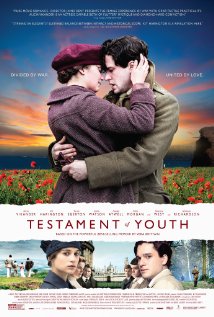

Testament of Youth (directed by James Kent), from Vera Brittain’s memoir, screenplay by Juliette Towhidi: A World War One film in the year when idealising Gallipoli was big in the headlines, it doesn’t focus on the battlefield but on the effects of the war on the combatants and their families and loved ones. It makes a powerful pacifist argument.

Meet the Patels (Geeta Pavel, Ravi Patel 2014): We saw this at the Sydney Film Festival. It’s unlikely to get a theatrical release, but it’s a very funny documentary about match-making among first generation Americans of Indian heritage. It’s really about intergenerational relationships. The EA says it’s a must-see for every parent.

He Named Me Malala (Davis Guggenheim 2015): Another documentary, this one could be seen as hagiographic, but Malala Yousafzai is a remarkable young woman. I loved the way she spoke with the absolutism of teenagehood from a position of influence to tell the president of Nigeria to do his job and ensure the safety of the girls abducted by Boko Haram.

The Emerging Artist’s other two:

Selma (Ava DuVernay 2015): A flawed movie, but it conveyed the experience of ordinary people taking part in Civil Rights marches. The leadership of the march across the bridge was particularly interesting: how to think strategically, resisting the push to be seen to take ‘decisive action’. The filmmakers weren’t given permission to use Martin Luther King Jr’s actual speeches, but the ones written for the film caught his style brilliantly.

The Dressmaker (Jocelyn Moorhouse 2015): The humour, the flamboyance, the over-the-topness of it. Kate Winslett was marvellous. So was Hugo Weaving. In fact, there were no weak performances.

My other two:

Ex Machina (Alex Garland 2015): The thing that stays in my mind is the image of the artificially intelligent creations – a fabulous effect where we see the cogs and wheels whirring away inside what is otherwise a human head. The story worked very well too.

Far from Men (David Oelhoffen 2014): Apart from enjoying the easy irony that there were only men in most of the film (should it have been called Far from Other Men?), I was transfixed by this slow, beautiful film of a pied noir (Algeria-born white Frenchman) escorting an Arab prisoner through the austerely photogenic Atlas Mountains.

The EA’s top five books:

The EA’s reading year was bookended by titles that brought home the harshness of the oppression of gay men and lesbians, even in times and places where one might think it was comparatively mild. Damon Galgut’s Arctic Summer deals with novelist E M Forster’s agonising life in the closet, and the part of Magda Szubanski’s memoir, Reckoning, that tells the story of her coming out is genuinely harrowing.

But those books are in addition to her actual top five. Here are those, with her comments:

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: This is a bracing book that everyone needs to read. We all know about climate change in a general way, and we know that powerful vested interests fight attempts to respond effectively. Naomi Klein gives detail and challenges us not to look away.

Jean Michel Guenassia, The Incorrigible Optimists Club: A novel about Soviet bloc refugees in Paris at the time of the Algerian War of Independence, this includes a coming of age story.

Biff Ward, In My Mother’s Hands: Excellent memoir of a 50s childhood. Buff Ward’s father was prominent left wing historian Russel Ward, so the domestic story includes elements of red-baiting. But the real power of the story is in her mother’s intensifying irrationality and the family’s attempts to deal with it.

Russell Shorto, Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City: The birth of liberalism without the US-style individualism. This is not a travel book. It’s very accessible, thoroughly researched history that compelled at least one person to read big chunks aloud to her partner. The history of Europe looks different after reading this .

Vivien Johnson, Streets of Papunya: Vivien Johnson has been involved with the Western Desert artists for decades. An earlier book told the story of the great Papunya Tula artists. This book tells the story of Papunya itself, especially after many of those artists left. Art is still being made there, by a new generation, mostly women.

My top five books:

I read at least 12 books in 2015 that did what you always hope a book will do: delighted, excited or enlightened me, changed the way I felt and/or thought about the world. I whittled the list down to five by selecting only books that touched my life in explicit ways. Here they are i order of reading:

John Cornwell, The Dark Box (2014): A history of the rite of Confession in the Catholic Church. The confessional was a big part of my childhood. I’ve dined out on a story of going to confession with Brisbane’s Archbishop Duhig when I was about thirteen. He asked in a booming voice that I was sure could be heard by everyone in the cathedral outside, ‘Would these sins of impurity have been alone or with others?’ Cornwall’s book felt like a very personal unpicking of that moment and the whole cloth it was spun from.

Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (2014). What can I say? I’m white. In laying out the way a word or phrase between friends or strangers can disrupt day-to-day life, so that the ugly history of racism makes itself painfully present, and linking those moments to the public humiliations of Serena Williams and the violent deaths of so many young African-American men, the book is a tremendously generous gift. It and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me share this generosity of spirit.

David Malouf, A First Place (2015): I haven’t blogged yet about this collection of David Malouf’s essays. It feels personal to me because David lectured me at university, but also because he is a Queenslander, and these essays explore what that means. Even though he is from what we in north Queensland used to call ‘Down South’, these essays fill a void I felt as a child – I was a big reader, but the world I read about in books only ever reflected the physical world I lived in as an exotic place.

Stan Grant, Talking to My Country (2016): I was privileged to read this ahead of publication. Stan Grant is a distinguished Australian TV journalist. This book, part memoir, part essay, gives a vivid account of growing up Aboriginal. It includes the most powerful account of a ‘mental breakdown’ I have ever read, not as a medicalised episode of ‘depression’, but as the result of generations of pain inflicted by colonisation refusing to stay at bay.

Jennifer Maiden, The Fox Petition (2015): I love this book in all sorts of ways. I love the way the image of the fox recurs – a literal fox, a fox as in Japanese folk lore, Whig politician Charles Fox. I love the chatty voice, and Jennifer Maiden’s trademark linebreaks after the first word of a sentence. I love the argumentativeness. I love the playful, almost silly, resuscitation of the distinguished dead to confront those who claim to be inspired by them. I love the way Jennifer Maiden makes poetry from the television news the way some poets do from flowers.

And now, on to 2016! I’m already about eight books behind in my blogging.