Evelyn Araluen and Jonathan Dunk (editors), Overland 253 (Summer 2023)

(Some of the content is online at the Overland website – I’ve included links)

This Overland begins with a trio of generational contrasts.

First, gen x-er Brigid Rooney, Associate Professor of English at Sydney University has an article on the late Professor Elizabeth Webby in which, though she describes herself as a friend of her subject, she maintains a serious academic distance where you can feel a more personal tone struggling to assert itself.

Second, baby-boomer John Docker, also an Associate Professor at Sydney Uni, has a review article on a book about Sydney’s New Theatre. He begins with a convincing account of himself as a non-theatre person, and one, moreover, who is strangely ill at ease when he visits the current site of the New Theatre, which is about ten minutes by car from the suburb where he currently lives. Amusingly self-indulgent, but it might have been better to reject the commission.

In the third item, Dženana Vucic, self-identified as a millennial, has a piece about Sailor Moon, a manga serial that was big in her 1990s childhood and I’m sorry to say of very little more interest to me after reading her article than it was before – though I enjoyed the complex irony in which she pretended to claim a deeply anti-capitalist message in the show.

After that, things get serious with ‘Prison healthcare as punishment‘ by Sarah Schwartz, a gruelling article which begins with the grim statement that an Aboriginal woman ‘passed away on the floor of a prison cell on 2 January 2020, after days of crying out for help.’ It continues, ‘Three years later, a Coroner found that if she had received the healthcare she needed, she would not have died.’ It’s a penetrating look at the way for-profit prison healthcare in Victoria and other Australian states leads to terrible outcomes, especially for First Nations people. A year after the coronial findings mentioned in its first paragraph no one had been held accountable for the neglect.

Of the poetry, curated by Toby Fitch, ‘Water under the bridge‘ by Jeanine Leane stands out. Among other things, it looks at the way different generations of First Nations people have responded to colonisation. The title phrase takes on a telling ambiguity:

that there were names in the river

that were not just water under a white man's

bridge

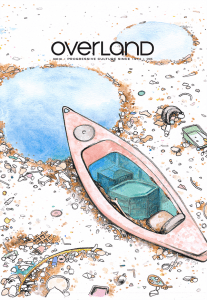

Fiction editor Claire Corbett has gathered four excellent, diverse short stories. ‘Parliament‘ by Simon Castles is a sketch of young love and protest on the lawns of the new Parliament House in Canberra in 1988. Anna May Samson, currently starring in the dreadful Australian spin-off of Death in Paradise, packs a complex set of relationships into a very few pages in ‘Summer work‘. ‘Hot season‘ by Anna Quercia-Thomas is a post-apocalyptic pastoral vignette. In ‘At first, nobody died‘ by Nasrin Mahoutchi-Hosaini the protagonist, herself an immigrant, is on vacation from her work as a counsellor of ‘boat people’.

It took me a long time to read this journal. It wasn’t for lack of interest.

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country, where the weather is swinging back and forth between a nurturing warmth and a chilly wind that murmurs in the casuarinas. I acknowledge Elders past and present for their continuing custodianship of this land.