I didn’t expect to attend a NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Dinner this year. For a while back there it looked as if the awards might go the way of the Queensland equivalent, but the Liberal Party-approved panel’s unpublished report must have come down in favour of continuation, because here they were again last night, six months late, run by the State Library rather than the Arts NSW, charging $200 [but see Judith Ridge’s comment] for a book to be considered, and sharing the evening with the History Awards, but alive and kicking. And pretty special for me, because I got to go as my niece’s date, my niece being Edwina Shaw, whose novel Thrill Seekers was shortlisted for the UTS Glenda Adams Award for New Writing.

The dinner was held in the magnificent reading room of the Mitchell Library. Not everyone approved of the venue – I was in the Research Library in the morning when a woman complained very loudly that she had driven the four hours from Ulladulla only to find the Mitchell’s doors were closed for the day so it could be converted into a banquet hall. She must have been placated somehow because she stopped yelling, but there were other problems. None of the shortlisted books were on sale – Gleebooks had a table at this event for years [but see Judith Ridge’s comment], as the Library has its own shop, which wasn’t about to stay open late just for us. And library acoustics aren’t designed for such carryings-on: the reverberation in the vast, high-ceilinged room made a lot of what was said at the mike unintelligible at the back of the room. But those are quibbles. It’s a great room with happy memories for a good proportion of the guests.

Aunty Norma Ingram welcomed us to country, inviting us all to become custodians of the land.

Peter Berner was the MC. He did OK, but organisers please note: the MC of an event like this needs to be literate enough to pronounce Christina Stead’s surname correctly.

The Premier didn’t show up. Perhaps he was put off by the chance of unpleasantness in response to his current attack on arts education. The awards were presented by a trio of Ministers, one of whom read out a message from the Premier saying, among other things, that art in all its forms is essential to our society’s wellbeing. But this was a night for celebrating the bits that aren’t under threat, not for rudely calling on people to put their money where their mouths are.

The Special Award, sometimes known as the kiss of death because of the fate met by many of its recipients soon after the award, went to Clive James – whose elegant acceptance speech read to us by Stephen Romei necessarily referred to his possibly imminent death. He spoke of his affection for New South Wales, of his young sense that Kogarah was the Paris of South Sydney, and his regret that he is very unlikely ever to visit here again. He also said some modest things about what he hoped he had contributed.

After a starter of oyster, scampi tail and ocean trout, the history awards:

NSW Community and Regional History Award: Deborah Beck, Set in Stone: A History of the Cellblock Theatre

The writer told us that the book started life as a Master’s thesis, and paid brief homage to the hundreds of women who were incarcerated in early colonial times in the Cellblock Theatre, now part of the National Art School.

Multimedia History Prize: Catherine Freyne and Phillip Ulman, Tit for Tat: The Story of Sandra Willson

This was an ABC Radio National Hindsight program about a woman who killed her abusive husband and received lot of media – and wall art – attention some decades back. Phillip Ulman stood silently beside Catherine Freyne, who urged those of us who enjoyed programs like Hindsight to write objecting to the recent cuts.

Young People’s History Prize: Stephanie Owen Reeder, Amazing Grace: An Adventure at Sea

This book won against much publicised Ahn Do on being a refugee (The Little Refugee) and much revered Nadia Wheatley on more than a hundred Indigenous childhoods (Playground). It not only tells the story of young Grace Bussell’s heroic rescue of shipwreck survivors but, according to the evening’s program, it introduces young readers to the ‘basic precepts of historical scholarship’. It also looks like fun.

General History Prize: Tim Bonyhady, Good Living Street: The Fortunes of My Viennese Family

A member my book group rhapsodised about this book recently, comparing it favourably to The Hare with Amber Eyes. It’s a family history, and in accepting the award Bonyhady told us it had been a big week for his family because the lives of his two young relatives with disabilities would be greatly improved by the National Disability Insurance Scheme introduced by the Gillard government.

Australian History Prize: Russell McGregor, Indifferent Inclusion: Aboriginal People and the Australian Nation

This looks like another one for the To Be Read pile. Russell McGregor acknowledged Henry Reynolds and Tim Rowse as mentors.

After a break for the entrée, a creation in watermelon, bocconcini and tapenade, it was on to the literary awards:

The Community Relations Commission Award: Tim Bonyhady was called to the podium again for Good Living Street, but he’d given his speech, and just thanked everyone, looking slightly stunned.

The newly named Nick Enright Prize for Drama was shared between Vanessa Bates for Porn.Cake. and Joanna Murray-Smith for The Gift. Perhaps this made up to some extent for the prize not having been given two years ago.

Joanna Murray-Smith said she learned her sense of structure from the Henry Lawson stories her father read to her at bedtime. As her father was Stephen Murray-Smith, founding editor of Overland, she thereby managed to accept the government’s money while politely distancing herself from its politics. She lamented that her play hadn’t been seen in Sydney and struck an odd note by suggesting that the Mitchell Library and a similarly impressive building in Melbourne may have been the beginning of the Sydney–Melbourne rivalry: I wonder if any Sydney writers accepting awards in Melbourne feel similarly compelled to compete. Vanessa Bates couldn’t be here, so her husband accepted her award, with his smart phone videoing everything, perhaps sending it all to her live.

The also newly named Betty Roland Prize for Scriptwriting (and I pause to applaud this conservative government for honouring an old Communist in this way): Peter Duncan, Rake (Episode 1): R v Murray

Peter Duncan gets my Speech of the Night Award. He began by telling the junior minister who gave him the award that he was disappointed not to be receiving it from Barry O’Farrell himself, because he had wanted to congratulate Barry on the way his haircut had improved since winning the election. At that point we all became aware that Peter Duncan’s haircut bears a strong resemblance to the Premier’s as it once was. He then moved on to congratulate the Premier for instituting a careful reassessment of the Literary Awards and deciding to persevere with them. He expressed his deep appreciation of this support for the arts. (No one shouted anything about TAFE art education from the floor. See note above about this being an evening to celebrate the bits that aren’t under threat.)

The Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children’s Literature: Kate Constable, Crow Country (Allen & Unwin)

I hadn’t read anything on this shortlist, I’m embarrassed to confess. It looks like a good book, a time-slip exploration of Australian history.

The Ethel Turner Prize for Young People’s Literature: Penni Russon, Only Ever Always (Allen & Unwin)

Again, I hadn’t read any of the shortlist. But Bill Condon and Ursula Dubosarsky were on it, so this must be pretty good! Penni Russon’s brief speech referred to the famous esprit de corps of Young Adult writers: ‘You guys are my people.’

There was break for the main course to be served, and for about half the audience go wander and schmooze. I had the duck, the two vegetarians on our table were served a very fancy looking construction, only a little late. Then onward ever onward.

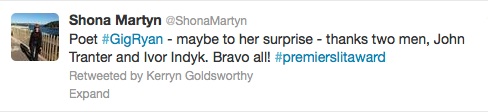

The Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry: Gig Ryan, New and Selected Poems

Again, I hadn’t read any of the shortlisted books, but wasn’t surprised that Gig Ryan won, as this is something of a retrospective collection. She speaks rapidly and her speech was completely unintelligible from where I was sitting (like some of her poetry). However, someone tweeted a comment that got laughs from the front of the room:

The Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-fiction: Mark McKenna, An Eye for Eternity: The Life of Manning Clark

Another lefty takes the government’s money, and a good thing too.

The UTS Glenda Adams Award for New Writing: Rohan Wilson, The Roving Party (Allen & Unwin)

I know nothing about this book. Rohan Wilson is in Japan just now. His agent told us that when she asked him for an acceptance speech ‘just in case’, he emailed back, ‘No way I’ll win – look at the calibre of the others.’ The three writers on my table who were in competition with him seemed to think it was a fine that it had won:

Favel Parrett and Edwina Shaw respond to not winning the UTS Glenda Adams Award for New Writing

The Christina Stead Prize for Fiction was almost an anti-climax. It went to Kim Scott for That Deadman Dance. We had a small bet going on my table, and I won hundred of cents. Kim Scott’s agent accepted on his behalf.

There was dessert, layered chocolate and coffee cake, then:

The People’s Choice Award, for which voting finished the night before, went to Gail Jones for Five Bells. She was astonished, genuinely I think, and touched that her book about Sydney as an outsider should be acknowledged like this. I haven’t read the book yet, but I’m also a bit astonished, because what I have read of her prose is not an easy read.

Book of the Year: Kim Scott, That Deadman Dance. No surprise there!

No surprise, either, that the award to Clive James overshadowed all the others in the newspaper reports.

I believe that the judging panel for next years literary awards has had its first meeting. The dinner will move back to the Monday of the week of the Writers’ Festival, where it belongs.

Added later: Edwina has blogged about the evening.

-33.875184

151.172380