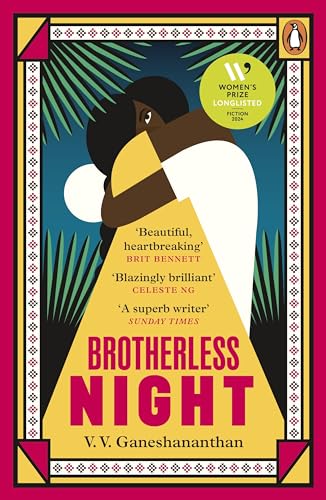

V. V. Ganeshananthan, Brotherless Night (Penguin 2024)

The main character and narrator of Brotherless Night, Sashi to her friends, is a young Tamil woman who is studying to become a doctor in the city of Jaffna in northern Sri Lanka. She lives through the beginnings of the civil war in the 1980s. Her beloved eldest brother is killed in the anti-Tamil riots of 1983 – the riots that are made so vividly present in S. Shakthidharan’s play Counting and Cracking. Two more brothers join the Tamil Tigers (the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam), and K, a man she has loved since childhood, becomes a celebrated hero and martyr among the Tigers.

Sashi herself is caught between an oppressive government army and a ‘liberation’ force that ruthlessly kills many of the people they claim to be defending. Sashi deplores the tactics of the Tigers, but she works for them in a secret clinic, patching up wounded cadres and civilian casualties, and she can never renounce her love for her brothers and K.

In a pivotal sequence, K comes out of hiding to ask Sashi for her support in a dangerous undertaking: to do so will align her publicly with ‘the movement’, which would grievously misrepresent her sympathies, but not to do it would be to betray a childhood friend. I think of E. M. Forster’s much quoted line: ‘If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.’ But Sashi’s choice is not as simple as that.

As she ponders the dilemma, there’s this line (on page 238):

Before there was a movement there were six children on a lane.

It is her loyalty to the vision of themselves as children that is at the heart of the book – that is, her loyalty to a basic shared humanity, and to telling the truth from that place.

It’s a terrific story. I was invested in the characters and sorry to put the book down. Part of its strength is the way it reaches out from its fictional world to highlight elements of actual reality. I can think of three ways.

First, other texts are referred to and integrated into the narrative. The books that Sashi and her brothers read might make an interesting reading list, but most strikingly Sashi and her Anatomy professor start a book group for woman at the university, and at their first meeting they discuss Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World, a real book by Sri Lankan author Kumari Jayawardena. In lesser hands this might have felt like analysis being shoehorned into the narrative, but we share the young women’s intellectual excitement, and their sense of peril as no one can be sure things won’t be reported back to the Tigers, with potentially dire consequences.

Second, there are elements of roman à clef. The salient features of K’s life and especially death, for instance, align closely with those of Tiger leader Theelipan.(Don’t look up this link if you want to avoid spoilers.) One of the book’s epigraphs – ‘There is no life for me apart from my people.’ – signals another real-life equivalent. It’s from Rajani Thiranagama (Wikipedia page here), a human rights activist who was once a member of the Tigers but became critical of them and was eventually believed to be murdered by them. She is the model for Sashi’s Anatomy professor, and the last third of the book features a fictional version of her real-life project of gathering evidence of atrocities committed by Tigers, Indians and Sri Lankan military.

The third way may be peculiar to me.

A young woman has been viciously assaulted by an Indian soldier – nominally there as part of a peace-keeping force. Sashi treats her injuries, and she returns later in a different, devastatingly vengeful role. This young woman’s name, Priya, rang a bell for me, and for no reason I could pinpoint I felt a particular investment in her story. Then I remembered the source of the bell: Priya Nadesalingam, the subject of a huge amount of press in Australia in 2023 (here’s one link in case you need reminding). That Priya, who had sought asylum in Australia with her husband Nades Murugappan and their two daughters, had become part of the community in the tiny Queensland town of Biloela. After a dawn raid, they came close to being deported and sent back to Sri Lanka. There was a huge public outcry and, long story short, the family are now living in Biloela on permanent visas.

The two Priyas have very different stories, but the coincidence of names brings home to me with tremendous force the horrific broader reality behind the bloodless statements about refugees made by politicians in Australia (and I assume elsewhere in the West).

The book doesn’t preach or lecture, but it brings a deeper understanding, not only of the struggle for Tamil independence in Sri Lanka, but of resistance movements generally. It makes me want to be a better person living in a kinder country with broader horizons.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora nation. I acknowledge their Elders past present and emerging, and gratefully acknowledge their care for this land for millennia, as well as the generosity I have personally experienced from First Nations people all my life.