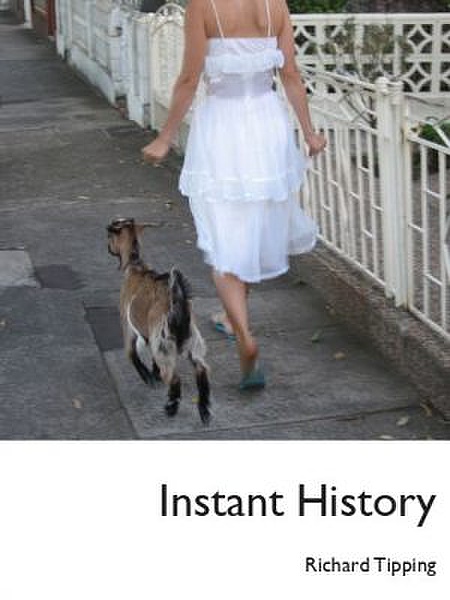

Richard Tipping, Instant History (Flying Island Poets, 2017)

As a subscriber to Flying Island Poets, I receive a bundle of ten books at the start of each year. The pocket-sized books belie their miniature appearance by being substantial poetry collections. Taken as a bundle they are wonderfully various – poets being published for the first time and poets with established reputations, embittered old poets and bright-eyed young ones, Chinese poets and poets from rural Australia (Flying Island’s co-publishers are Cerberus Press in Markwell via Bulahdealh and ASM in Macao).

I was delighted to find Instant History in my bundle this year. Richard Tipping is a multi-disciplinary creator whose work I have been encountering and enjoying for more than 50 years.

Probably my first encounter was the poem ‘Mangoes Are Not Cigarettes’ performed as a duet with Vicki Viidikas in the Great Hall at Sydney University in the early 1970s, then reprised immediately as ‘Oysters Are Not Cigarettes’. (That poem lives on – I just found the text, with photos, on Michael Griffith’s blog at this link.)

Tipping’s ‘signed signs’ appear regularly at Sydney’s Sculpture by the Sea. Photos of a couple of them have featured in recent issues of Overland: in issue 255 two chunky rocks near the shoreline bear gold leaf lettering, ‘SEA THREW’; in issue 256 a road sign reads, ‘FORM 1 PLANET‘.

Tipping’s Wikipedia page lists poetry, art, spoken word, documentary films, an art gallery, and more. Yet he doesn’t look at all exhausted in his cover photo.

Instant History bristles with quotable lines. Rather than focusing on just page 78*, here goes with a brief description of each of its four parts and a couple of lines from each.

‘The Postcard Life’ comprises 33 mostly short, impressionistic poems that are like, well, postcards from travel destinations from New York City to the Malacca Strait. My favourite in this section is ‘Snap’, a collection of short poems that are either haiku-like or snapshot-like, depending on your point of view, that capture a visit to Japan, individually and cumulatively wonderful. For example:

Bullet train to Kyoto

speeding by still river, reflecting rain

Chain-smoking chimneys

Greyroofed villages, rice fields, cement

‘Rush Hour in the Poetry Library’, for me the most memorable section, has 28 poems that are mainly about art and works of art. I particularly like ‘On Film (for Steve Collins, editor)’, which reads to me as a poem gleaned from conversations with its dedicatee. It begins with this resonant paradox:

Film is painting in light with time

for the ears' extra pleasure

even if the pictures are better on radio

‘Earth Heart’ has just nine poems, and includes images of his typographic visual poem ‘Hear the Art (Earth Heart)’ – if you write either of those phrases out a couple of times without word spaces, you have the poem, a wordplay that absolutely sings. Its appearance in this book is one of many manifestations. For a land art version in the grounds of the Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, you can go to Richard Tipping’s website.

‘Kind of Yeah’, the final section, feels mostly like a bit of fun with the vernacular, nowhere more so than in ‘Word of Mouth’ which includes this:

It was hair-raising, pulling your leg, turning the other cheek; quick as a wink you got me by the short and curlies just as I'd finally got my arse into gear.

That’s just a taste. There’s politics, Buddhism, whimsy, and always a sense of performance, in the best senses of the word.

I wrote this blog post on land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, and finished it in a brief pause from heavy rain. I acknowledge the Elders past and present of this country, never ceded, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice, honoured in the breach here, is to focus on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently 78.