My friend Swapna Dutta is a writer, translator and editor, mainly of children’s literature, who lives in Bangalore, in southern India. The School Magazine published some of her stories when I was editor, and she and I have kept in touch over the intervening years. Swapna mentioned in a recent email that she had translated a children’s book, The Arakiel Diamond, from Bengali into English, and asked if I’d like a copy. Of course I was interested, and a couple of days later it arrived in my letter box, with three other books. It’s been a treat and an education to read all four.

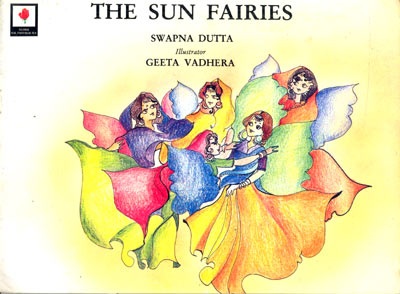

Swapna Dutta and Geeta Vadhera, The Sun Fairies (National Book Trust, India 1994, 2001)

The Sun Fairies is a tiny picture book that plays around with science and fantasy. That is to say, it’s a fanciful account of the origin of clouds – some fairies who live in the sun build castles in the sky so it won’t be so bare and empty – that ends up being a decorative but accurate account of how the water cycle works: the cloud castles are made from water, air and dust, and when they get too heavy they fall to the earth as water. The fairies have discovered ‘a never-ending game’. The illustrations, by Geeta Vadhera, are fabulous. I see from the Internet that Ms Vadhera has gone on to international renown. This may be her only children’s book.

Swapna Dutta, Plays from India, illustrated by Baraan Ijlal (Rupa & Co 2003)

In some ways each of the other books is a work of translation. In Plays from India three episodes from Indian history are shaped into dramas suitable for performance by school students. In my ignorance I don’t know whether the stories would be familiar to most Indian students, so I can’t tell whether the history or the theatre is the main point. I was interested in both.

Swapna Dutta, Folk Tales of West Bengal , illustrated by Neeta Gangopadhya (Children’s Book Trust 2009)

Folk Tales of West Bengal retells sixteen tales. Swapna has an article at papertigers from which I learned that what the Grimms were for Germany, and Moe & Asbjørnsen for Norway, the imposingly named Dakshinaranjan Mitra-Mazumdar was for what is now Bangladesh and West Bengal. At least some of the tales here were collected by him in the first decades of last century. Unsurprisingly to anyone who has entered the woods of Re-enchantment, there’s a lot in these stories that’s familiar to a reader brought up on European-origin fairy stories: kings and princesses, talking animals, metamorphoses, riddles, lost and found children, supernatural beings who reward the humble and punish the greedy. There’s also a lot that’s different: the heroine of the first story, for instance, is not a seventh child but a seventh wife. This blending of familiar and unfamiliar makes for a delightful read.

Sucitrā Bhaṭṭācārya, The Arakiel Diamond, translated by Swapna Dutta and illustrated by Agantuk (Ponytale Books 2011)

The Arakiel Diamond is the only book in my swag that is not Swapna’s original work. It’s a detective story for young readers, one of a series featuring a Bengali housewife and her niece. A wealthy man dies. His most precious possession, the eponymous diamond, has gone missing, and almost everyone in his household – and there are many – has had motive and opportunity to steal it. The plot has exactly the twists you’d expect, but the detectives’ relationship and the details of their domestic life are well captured, and I learned a lot about the Armenian community in Calcutta, in a way that reminds me of grown-up detective writers (Sarah Paretsky comes to mind) who take us to a new subculture in each novel.

The four books had me reflecting on multiculturalism in children’s literature. We make fun of the way US children’s publishers, apparently believing that their intended readers would shrink from anything not immediately recognisable as of the US, re-edit books from elsewhere in the English-speaking world to remove unsightly exotica. They don’t just want a world where British characters spend dollars and cents, or Australians walk on a pavement, weird as such a world might be. I remember hearing of a New Zealand novel whose publisher suggested the book’s Maori issues might be more accessible to US children if the setting was changed to California – that author held firm and the book still found readers, even got made into a movie.

I wish now to acknowledge that I’m a bit of a kettle to the US publishers’ pot. Though I enjoyed the slight cultural disorientation I felt as I read these books, I caught myself thinking young readers would be put off by it. To make the books accessible to Australian 11-year olds, the unexamined internal argument went, you’d have to do something about lakh and crore, lunghi, salwar shameez and rakhi, not to mention the nitty-gritties of the game of chess or a casual use of thrice in conversation. On reflection, I think that argument profoundly misunderstands how young people read. The only thing that universally distinguishes young from adult readers is that the young ones are younger. One result of this is that they know they don’t know everything about the world, and mostly when they read there are words they don’t recognise but have to guess from the context. (I loved and understood pulverise and invulnerable in Superman comics long before I could define them.) So you might not know what a lunghi is, but the context tells you it’s an article of clothing, and there’s even an illustration to help. Likewise, lakh and crore are obviously big numbers, and that’s all you need to know. As I remember back to my own childhood reading, I think such things would have added spice to the book: if I was young now, I might even have fun googling them. As for nitty-gritties and thrice, I do think we can trust young readers to recognise when a word or a turn of phrase belongs to a different place. (Both my sons say zed in spite of seeing quite a lot of Sesame Street when young.)

I look forward to reading the books, Jonathan. Thanks again for a great post.

LikeLike