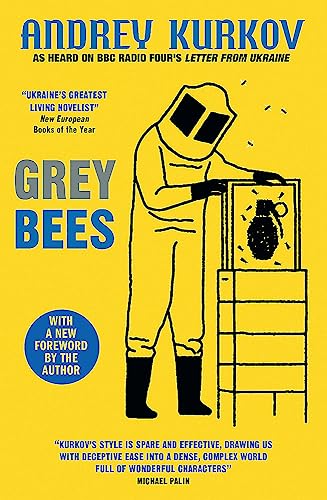

Andrey Kurkov, Grey Bees (2018, translation by Boris Dralyuk, MacLehose Press 2020, 2022)

Before the meeting: I hadn’t heard of Andrey Kurkov before this book was nominated for the Book Group. He’s a Ukrainian novelist, children’s writer, essayist and broadcaster. In an interview on PBS early last year he said that, though he is ethnically Russian and writes in the Russian language, Putin’s invasion has made him ashamed to be Russian, and he is now considering writing only in Ukrainian. He finds it impossible to write fiction in the current situation, but he continues to write and broadcast about the war – his series of broadcasts for the BBC, ‘Letter from Ukraine’, is available online.

Grey Bees, originally written in Russian, was first published in 2018. Russia had annexed Crimea, and there was armed conflict with Russian separatists in two breakaway ‘people’s republics’ in the Donbas region in the eastern part of Ukraine. The novel is set in a time when the front between those forces stretched for about 450 kilometres (it’s now closer to three thousand). The area between the fronts is known as the ‘grey zone’. In his useful Preface to the 2020 English edition, the author explains:

Most of the inhabitants of the villages and towns in the grey zone left at the very start of the conflict, abandoning their flats and houses, their orchards and farms. Some fled to Russia, others moved to the peaceful part of Ukraine, and others still joined the separatists. But here and there, a few stubborn residents refused to budge. … No one knows exactly how many people remain in the grey zone, inside the war. Their only visitors are Ukrainian soldiers and militant separatists, who enter either in search of the enemy, or simply out of curiosity – to check whether anyone’s still alive. And the locals, whose chief aim is to survive, treat both sides with the highest degree of diplomacy and humble bonhomie.

(Page 12–13)

Sergey Sergeyich, the hero of Grey Bees, lives in a tiny village in the grey zone, one of two cantankerous old men who have refused to leave. The electricity has been cut off. He has to trek to the next village to buy food. He depends on a charity’s annual delivery of coal for heating through the savage winter. He is a beekeeper, whose emotional life focuses on the wellbeing of the beehives that spend the winter in his garden shed. His wife and daughter are long gone, and he has never really got along with Pashka, the other remainer.

The opening scenes reminded me of Czech comedies in the 1960s like The Firemen’s Ball. There, people’s lives were miserable under the Soviet regime and the comedy was subversive as well as desperately funny. Here the enemy is the war itself, and the quiet desperation of the characters is made tolerable to the reader by their comic focus on tiny issues – like the way the two men hide from each other whatever good food they’ve managed to get hold of (where good food can include a block of lard!), or Sergey’s decision to swap the street signs so he no longer lives in Lenin Street. There’s a touch of Waiting for Godot: how can anything happen so long as they are trapped in this place?

Then, as the days warm up and the buzzing of his bees becomes more demanding, Sergey decides to take them to a place that hasn’t been laid waste by the war, and we follow him on a journey south, to environments that are more friendly to him as well as his bees. He meets with kindness, and is kind in return. He sets out to visit a Tatar beekeeper he met at a conference years before, and arrives in a tiny village in Crimea that is occupied by the Russians. In the process of getting there he has to pass through Russian checkpoints, and he is looked at with suspicion on all sides: coming from Donbas, is he a separatist or a loyal Ukrainian? He’s attacked on suspicion of being one and harassed when he is assumed to be the other. An Orthodox man, he falls foul of the Russian authorities when he befriends a Muslim family.

Though terrible things happen, what shines through is Sergey’s unassuming human kindness. The background buzzing of the bees is warmly reassuring: they go about their work, and can be counted on to produce honey, which is universally welcomed.

Towards the end, when the Russian authorities meddle with one of the hives, Sergey has dreams that the bees of that hive have turned monstrously grey, and the allegorical role of the bees, which is a quiet undercurrent for most of the book, comes front and centre in some splendidly surrealistic passages.

To give you a taste of the writing, here’s a little from page 76, when Sergey is still in the village. Spring is on the way:

The sun had spread even more of its yellowness through the yard. The trampled snow had turned yellow, as had the fence, and the grey walls of the shed and the garage.

It wasn’t that Sergeyich didn’t like it – on the contrary. But he felt that the sun’s unexpected playfulness, as appealing as it may be, disrupted the usual order of things. And so, in his thoughts, he reproached the celestial object, as if it could, like a person, acknowledge that it had acted improperly.

The artillery was whooping somewhere far, far away. Sergeyich could only hear it if he wished to hear it. And as soon as he went back to his thoughts, turning into Michurin Lane, its whooping melted away, blending into the silence.

In his preface to the 2020 edition, Andrey Kurkov says that on his visits to the grey zone he ‘witnessed the population’s fear of war and possibly death gradually transform into apathy’. Sergey’s dislike of disruption, even by warmth and playfulness, and the way he can be deaf to the whoops of the artillery, are ways of showing that apathy. It’s a terrific achievement of this book that it brings tremendous energy and compassion to bear on the person lost in apathy, and never loses sight of his enduring humanity.

After the meeting: It turned out this was an excellent choice for the group – someone awarded the Chooser two gold koalas, which must come from a children’s show I’ve missed out on.

Conversation looped around the Russian invasion of Ukraine, to other terrible events of recent days in the local and international scenes, sometimes becoming heated, but not acrimonious, and kept coming back to the book. I think it was Kurkov’s insistence on keeping close to the humanity of his characters, especially Sergey, focusing on what could be benign between people, even while not mitigating the horrors of the war. The father of one group member was Ukrainian, but always identified as Russian. He himself has never learned either language but he could speak a little of how the book stirred memories of his father. The rest of us lacked such a direct connection, but I think the general feel was that we came away from the book with a much more solid grasp of the depth and reach of the current war, and the centuries of Ukraine–Russia relations that preceded it.

I got blank stares when I mentioned The Firemen’s Ball.

I know Phillip Adams awards a ‘koala stamp’ to people he interviews and considers special in some way. Perhaps this is origin of the chooser’s award? Anyway, ‘Grey Bees’ will be on my reading list. And possibly ‘The Firemen’s Ball’ if I can find a copy.

LikeLike

Thank you. I didn’t want to display my ignorance at the Group. You’ve helped me out

LikeLike

And me too. I do listen to Phillip Adams on and off but I have obviously missed this. I thought maybe it was just your member being Aussie-clever about gold stars.

Anyhow, this book sounds really excellent. I have heard of course of remainers. Can’t understand them myself – well, in one sense, of course I can because it’s one’s home, but in the sense of wanting to survive, I can’t. Still it would have been pretty hard I assume to move his beehives.

Sounds like you had a good discussion too.

LikeLiked by 2 people