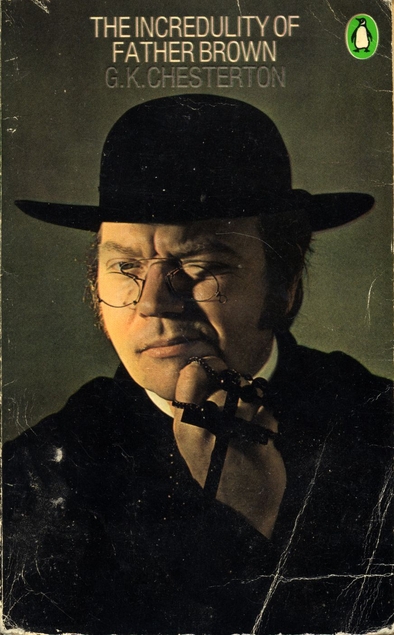

G K Chesterton, The Incredulity of Father Brown (©1926, Penguin 1958, reprinted 1970)

On my eleventh or twelfth birthday, my parents gave me The Father Brown Omnibus, a doorstop of a book containing all 53 of G K Chesterton’s Father Brown stories. If they hoped it would break my addiction to Agatha Christie and Ngaio Marsh, they were to be disappointed, but I did love Father Brown, and once I’d read all his stories, I sought out everything I could find by Chesterton: the autobiography, essays (including ‘On chasing after one’s hat’), his books on Francis of Assisi and Thomas Aquinas, Orthodoxy, some poetry (‘I don’t care where the water goes/ If it doesn’t get into the wine’) and more. I loved his way with paradox. I thought his aphorisms, ‘Blessed is he who expecteth little, for he shall often be surprised,’ and ‘Anything worth doing is worth doing badly’ were words to live by.

Then, having not read anything by him for roughly half a century, I found this slim, yellowing paperback in a street library.

The Incredulity of Father Brown was the third of five collections, and contains eight stories. Father Brown’s nemesis Flambeau doesn’t appear, and more action takes place in the USA than I remember. Most of the stories are locked-room mysteries: someone was murdered in a room that no one else could have got into or out of. There’s an arrow, a sword-stick and a noose, all ingeniously deployed, and a couple of corpses that aren’t who or what they seem. All the elaborately conceived crimes are solved by the brilliantly pragmatic but unassuming little priest (the reader doesn’t have a fighting chance of figuring them out).

Not all the murderers are arrested, or even identified. These aren’t stories in which the detective reassuringly restores order by bringing criminals to justice. The interest lies elsewhere: first in the pleasure of the puzzle, and secondly in the platform they provide for Chesterton to preach his particular form of Catholicism. This collection (and possibly the whole Father Brown corpus – I can’t claim to remember) has at its heart a paradoxical assertion that a man of faith like Father Brown is less vulnerable to being hoodwinked by ‘spiritual’ claims than a modern ‘secular’ person. In these stories, God is real and There’s a Perfectly Natural Explanation for Everything Else. Father Brown himself, usually mild-mannered and Britishly polite, has occasional angry outbursts about ‘heathen humanitarians’. The polemic gets most explicit in ‘The Miracle of Moon Crescent’:

‘By the way,’ went on Father Brown, ‘don’t think I blame you for jumping to preternatural conclusions. The reason’s very simple, really. You all swore you were hard-shelled materialists; and as a matter of fact you were all balanced on the very edge of belief – of belief in almost anything. There are thousands balanced on it today; but it’s a sharp, uncomfortable edge to sit on. You won’t rest till you believe something; that’s why Mr Vandam went through new religions with a tooth-comb, and Mr Alboin quotes scripture for his religion of breathing exercises, and Mr Fenner grumbles at the very God he denies. That’s where you all split: it’s natural to believe in the supernatural. It never feels natural to accept only natural things. …’

That’s rubbish of course. But the underlying paradox of a man of religion who is more immune to oogy-booginess than a wide range of hardboiled types is fun to read

My only specific Father Brown memory from 60 years ago wasn’t of anything in this book. It’s an observation in ‘The Vanishing of Vaudrey’ in The Secret of Father Brown. It took some searching, because I didn’t hve the exact words, but I found it eventually:

… there are two types of men who can laugh when they are alone. One might almost say the man who does it is either very good or very bad. You see, he is either confiding the joke to God or confiding it to the Devil.

Again, that’s nonsense, but I can testify that it’s memorable nonsense, because it lodged in my memory. I loved it for its audacity, or maybe just for its cleverness. And it’s the kind of thing I still enjoy in Chesterton. I should mention that there’s plenty of colonialism, racism, antisemitism and sexism (women being mainly absent in this volume). It’s hard to be an unqualified fan, but I’m not sorry to have revisited these stories.

Have you watched any of the TV series? I never did, until I brought my father down to aged care in Melbourne, and I visited him every day. He loved the Father Brown series, and so we watched our way through every series there was. I was fascinated to observe that though he had advanced dementia, he could still work who dunnit better than I could. The human brain is a most mysterious thing…

LikeLike

I haven’t watched the TV series. I think I felt a bit protective of my young reading self. And I still do. For a start the actor isn’t short and round and doesn’t look at all like a black mushroom

LikeLike

Avoid the TV series! It’s a travesty! Not even close to my memories of the cleverness of the books. I’m glad you were able to revisit Father Brown. I tried to a while ago and was seriously disappointed. For starters, I hadn’t remembered how religious they were, but now that you point it out I realise that’s essentially the point.

LikeLike

Yes, I was surprised at the insistence on religion. When I was young I suppose I just saw that as the equivalent of the boring bits of westerns where people just talked!

LikeLike

Ha ha! Or the bits in the Marx Brothers where Groucho was romancing Margaret Dumont!

LikeLike

Exactly! Where’s Harpo?

LikeLiked by 1 person