Anthony Joseph, Sonnets for Albert (Bloomsbury Poetry 2022)

I bought a copy of Sonnets for Albert after hearing Anthony Joseph’s brilliant chat with Felicity Plunkett at the Sydney Writers’ Festival earlier this year. The Albert of the title is the poet’s father who was mostly an absence during his childhood in Trinidad, where he was raised by Albert’s mother, who loved both of them. My blog post (here) on the Festival conversation gives some of the detail – and also some of Joseph’s interesting observations about the sonnet form and the relationship of Caribbean writers to the English language.

Almost every poem in the book is a sonnet. They don’t constitute a biography in verse, but skip about chronologically, from a childhood memory, to Albert’s final illness and death, to his period in New York City as a reverend. Some have a rich Caribbean music to them. Others are in effect prose poems, though they preserve the sonnet’s 14 lines with a turn in the middle.

It’s a terrific book. Albert emerges as a fascinating, charming rogue. The poet’s complex feelings for him, including deep affection, and grief at his death, are alive and contagious on the page.

Anthony Joseph lives in the UK, and the book is shot through with the expat’s love of his homeland. When I heard that he was from Trinidad, I mentally adjusted that to the nation’s name, Trinidad and Tobago. But the poems themselves are clear: he comes from Trinidad; Tobago is a different island and to have one’s father live there is to have an absent father.

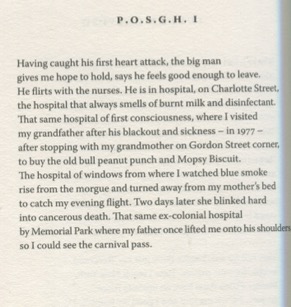

Page 76 is ‘P.O.S.G.H. I’, the first of two poems whose titles are the initials of the Port of Spain General Hospital (so it’s not just Sydney people who refer to hospitals by their initials – I live in walking distance of R.P.A.H.):

Shakespeare or Petrarch might not have recognised this as a sonnet. There’s no rhyme scheme, no formal metre, not even an obvious division into eight- and six-line sections. But it has its own music, which becomes clear if you read it aloud: in the first couple of lines, for instance, the echoing sounds in ‘hope to hold’ and ‘flirts with the nurses’ demand to be read slowly and liltingly. And the effect of the long lines becomes clearer when you read this poem alongside ‘P. O. S. G. H. II’ on the facing page. I won’t push the publisher’s tolerance by quoting that poem as well, but it deals with a later, more ominous hospital experience with Albert (called ‘the big man’ in both poems) and is made up of short lines, with dialogue, and a suggestion of Creole – ‘He eat up all the joy’.

There’s a leisurely, reflective feel to this poem, and emotive suggestions emanate from its long lines like smoke. A whole web of family relationships is evoked.

It begins with Albert:

Having caught his first heart attack, the big man

gives me hope to hold, says he feels good enough to leave.

He flirts with the nurses. He is in hospital, on Charlotte Street,

A lot is conveyed and suggested in that first line. That it was his first heart attack means that others were to follow, and though heart attacks aren’t contagious, the word ‘caught’ suggests that this one made ‘the big man’ vulnerable to more. As the sentence continues over the line break, the second line pulls back from these grim implications: there’s hope.

When my own father – a very different man from Albert – was close to death, a nurse came each day to wash him and make him comfortable. He too flirted – he joked about the lengths he’d had to go to to have a beautiful woman scrub his back: it’s a thing between men of a certain age and generation and women who care for them. It may not mean the man has recovered, but it’s a sign that he’s in good spirits. In the context of the rest of the book, we know that for Albert (unlike my father) it’s also a sign that he’s back to his disreputable normal, and there’s a hint that the poet’s relief is mixed with exasperation at the flirtiness. Attention turns away from Albert, to the hospital and the memories it evokes:

the hospital that always smells of burnt milk and disinfectant. That same hospital of first consciousness, where I visited my grandfather after his blackout and sickness - in 1977 - after stopping with my grandmother on Gordon Street corner, to buy the old bull peanut punch and Mopsy Biscuit.

That ‘always’ tells us a lot. This is a familiar place, as the rest of the poem spells out. ‘First consciousness’ could mean many things – perhaps even birth – but it certainly implies that the hospital has always been part of the poet’s world. In a beautifully compressed way, this line and what follows evoke key points of his family story. ‘My grandfather’ appearing after a line break enacts a kind of swerve away from the present to a moment in the past, to another sick man. It’s implied that his grandfather’s illness had some of the same unstated emotional impact as his father’s current illness, an implication reinforced by the way ‘the old bull’ echoes ‘the big man’.

My web search didn’t tell me anything about Mopsy Biscuit, and peanut punch may be either a popular Guinness-based drink for adults with rumoured aphrodisiac qualities (hmm, ‘the old bull’?), or a children’s drink, depending on where you look. Either way, the memory is essentially benign – the poet was 11 in 1977 and buying treats is what stands out in his memory of that event.

Right on cue at the end of line eight, the sonnet turns. The hospital is not always a place of healing or relatively carefree visits:

The hospital of windows from where I watched blue smoke rise from the morgue and turned away from my mother's bed to catch my evening flight. Two days later she blinked hard into cancerous death.

I try not to use words like enjambment and caesura, but wow, cop the enjambments and caesuras in these lines! That is to say, notice how the sense flows over the line breaks, and breaks sharply in the middle of lines, and how the echoing hard D sounds at the end of the second and third lines intensify those effects.

Another, heavier memory is stirred. The poet is older, visiting from elsewhere (Anthony Joseph moved to the UK in his early 20s). His mother is barely a presence, and when he turns away from her it’s with a bleak premonition of death in the blue smoke. There’s no hope to hold this time, and though both the flight and the death occur midline, they both have a feel of finality.

But the poem continues:

into cancerous death. That same ex-colonial hospital by Memorial Park where my father once lifted me onto his shoulders, so I could see the carnival pass.

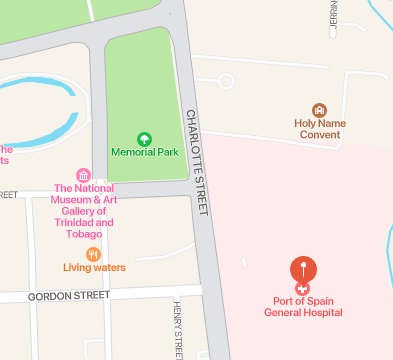

I love the way this poem is so firmly rooted in a place. The word ‘hospital’ rings like a chime – five times in 14 lines. The hospital is precisely situated, on Charlotte Street, opposite the corner of Gordon Street, by Memorial Park, and its architecture and history are evoked in the one word ‘ex-colonial’.

The poem ends with another turn, a kind of equivalent to the couplet that ends a classic sonnet. It’s as if after going on a short tour of the family – grandfather, grandmother, mother – we come back to Albert and can remember him, without the distancing irony of ‘the big man’, as ‘my father’. Loss is prefigured by the first heart attack, but there’s also a loss that happened long ago: the ‘once’ when his father lifted the poet on his shoulders is gone. It’s no coincidence that Memorial Park is mentioned here: this last moment of the poem has an elegiac feel to it. He was alive. He was my father. He lifted me on his shoulders. The carnival is over.

Very nice close reading of the poetic moves in this peice. Thanks J.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Ian. It’s interesting how much this poem yielded when I stayed with it like this

LikeLike

Pingback: Journal Catch-up 20 | Me fail? I fly!