David Marr, Killing for Country: A Family Story (Black Ink 2023)

I’m a member of two book groups. This month, they both focused on Killing for Country.

Before the meetings: An ‘ancient uncle’ asked journalist David Marr to explore their family history. As Marr complied, he came upon a photograph of one of his ancestors in the fancy uniform of the Native Police, the infamous organisation in which white officers led Indigenous men in extrajudicial killing sprees in lands that are now known as northern New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory. Marr realised that this was a significant project and set about writing the interwoven stories of his forebears and the Native Police.

I imagine most of the book’s readers will know the broad outline of genocidal massacre that was instrumental in taking possession of the land in these parts of Australia, as elsewhere. Most of us now know that the euphemistic language of ‘dispersal’ and ‘punitive expeditions’ covers terrible atrocities. For me, Ross Gibson’s 2002 book Seven Versions of An Australian Badlands was a turning point. Rachel Perkins’s monumental TV series, The Australian Wars (2022), did heroic work in dispelling any residual beliefs that Australia was settled peacefully, and the Native Police featured in the third, heartbreaking episode. Anyone wanting to cling to such beliefs is advised to stay away from Killing for Country.

Marr follows the thread of his own family’s story through the complex history. He doesn’t try to be comprehensive. He makes no mention, for instance, of the punitive expeditions led by Sub-Inspector Robert Johnstone in Mamu country, the part of Australia that I come from. And professional historians will no doubt find fault with his work – he is too concerned to push his agenda, perhaps, and not judicious enough in checking his sources for sensationalist or other motivations, the kind of criticisms made of Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore. It certainly won’t please the columnists of Quadrant or commentators on Sky News at Night. But, as Marcia Langston says on the front cover blurb:

If we want the truth, here it is told by David Marr.

Told by David Marr means told well. I attended one of the many public talks Marr has given about the book, and on that occasion I was struck by the heavily ironic way he spoke of the perpetrators and justifiers of colonial violence as profoundly respectable men. It felt wrong, somehow, to praise them, even in mirthless, defensive jest. The book does none of that. In writing it down, evidently, Marr had no need for such defences. But the reader, this one at least, needs to take frequent breaks.

This is a key part of White Australia’s foundation story: brutal mass killings, including breathtakingly callous first-person accounts, followed by pseudo-euphemistic newspaper accounts (‘with the usual results’ is one memorable phrase to indicate many deaths) or political justifications. When I was reading the book, I watched Prosecuting Evil, a TV documentary about Nazi murders of Jews, and some of the horrific footage was an exact match for scenes described in this book.

There were people at the time who named what was happening in terms we can recognise, and many of those voices are also present here.

This isn’t history that can be comfortably consigned to the distant past: Marr is writing about his own family, and about history that constantly chimes with the present, or perhaps has never gone away. ‘Let no one say the past is dead,’ Oodgeroo wrote. ‘The past is all about us and within.’

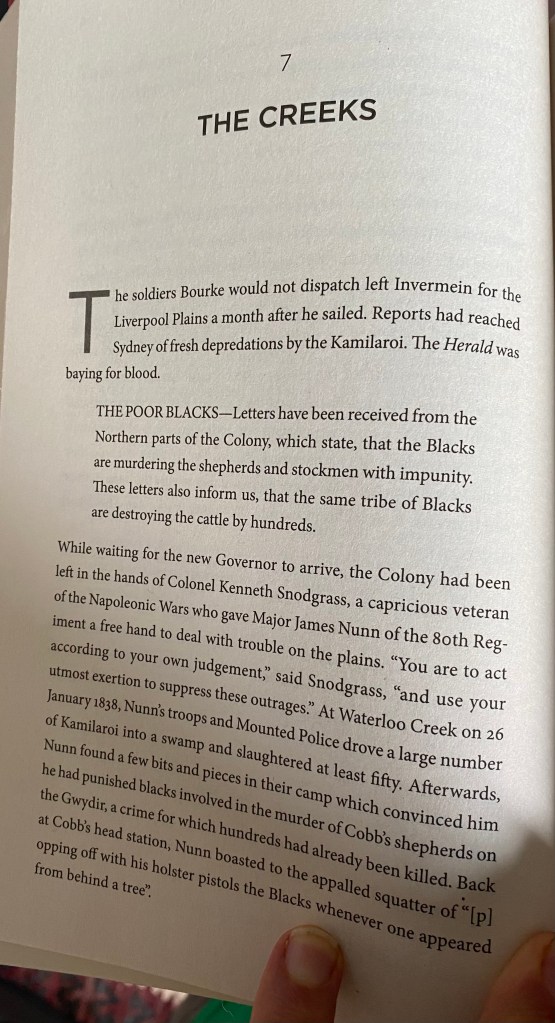

It’s my custom on this blog to have a close look at Page 76. Weirdly perhaps, that page, chosen arbitrarily because it’s my age, often shows a lot about a book.

In Killing for Country, page 76 is the beginning of Chapter 7, ‘The Creeks’, which deals with two massacres, at Waterloo Creek and Myall Creek, and their aftermaths – the first a whitewash, the second a major scandal and a court case spearheaded by Attorney General John Plunkett, one of the settler heroes of the book, leading to the execution of seven murderers, but also leading, as Marr points out, to secretiveness on the part of later murderers of Indigenous people.

This page is pretty much the full treatment of the Waterloo Creek massacre. The Native Police, the main subject of the book, have yet to be established, but this brief account of a massacre by white troopers is something of a template for much of what is to follow.

Governor Richard Bourke, having tried without success to limit the activities of the squatters in their treatment of convicts and the traditional owners of the land they claimed, resigned and sailed back to England . In December 1837. His successor George Gipps was to take office in February 1838. In the meantime:

Reports had reached Sydney of fresh depredations by the Kamilaroi.

It’s worth noting here that Marr take great care with names. While his sources, such as the quote from the Sydney Herald below, refer to ‘Blacks’, ‘tribes’, and so on, Marr himself always specifies which First Nations are being talked about, in this case the Kamileroi. This simple act has a powerful cumulative effect, as nation after nation comes into conflict with the military, with vigilante convicts, and with the Native Police.

The Herald was baying for blood.

THE POOR BLACKS- Letters have been received from the Northern parts of the Colony, which state, that the Blacks are murdering the shepherds and stockmen with impunity. These letters also inform us, that the same tribe of Blacks are destroying the cattle by hundreds.

‘Baying for blood’ may be the kind of thing that professional historians would steer clear of, but I like the way it spells out what the newspaper leaves unspoken (these people are murderers and mass destroyers of cattle, therefore …). Elsewhere, Marr quotes newspaper correspondence and other contemporary sources pointing out that the ‘murders’ and ‘destruction’ are perpetrated by people defending themselves against an invasion or avenging atrocities committed against them. Such arguments are roundly mocked by the mainstream as sentimental wailers ‘desirous of acquiring a reputation for humanity’ – the tone isn’t so different from some of our current media talking about virtue-signalling latte-sippers.

While waiting for the new Governor to arrive, the Colony had been left in the hands of Colonel Kenneth Snodgrass, a capricious veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, who gave Major James Nunn of the 80th Regiment a free hand to deal with trouble on the plains. ‘You are to act according to your own judgement,’ said Snodgrass, ‘and use your utmost exertion to suppress these outrages.’

The fabulously named Kenneth Snodgrass, deftly characterised and contextualised in seven words, makes no other appearance in this story, but his instructions foreshadow the vague instructions given to officers of the Native Police. Without fail, the politicians giving the orders retain deniability. Their intentions are clear, but they consistently refuse to give explicit instructions to kill. All the Native Police massacres were illegal, and directly counter to general policies emanating from distant Britain, but no one was ever held accountable for them. At Waterloo Creek, the troops and mounted police were white, and so even less likely to face legal consequences.

At Waterloo Creek on 26 January 1838, Nunn’s troops and Mounted Police drove a large number of Kamilaroi into a swamp and slaughtered at least fifty.

One of my difficulties with the book is that I often lose track of dates. For example, I kept waiting for the moment when the narrative would intersect Melissa Lucashenko’s novel Edenglassie, in which the Native Police play a role. But 1854, Edenglassie‘s year, comes and goes without being named. So the explicit dating of this incident stands out. Serendipitously, I’m writing this on 26 January, a public holiday when fewer people each year choose to celebrate Australia Day. I’m guessing that Marr was struck by the significance of the date and left it there as a grim easter egg. The Waterloo Creek massacre happened on the 50th anniversary of Arthur Phillip raising the Union Jack on Gadigal land. A hundred years later, William Cooper declared the date to be a day of mourning. Today there’s a struggle over whether it’s Australia Day or Invasion Day.

Afterwards, Nunn found a few bits and pieces in their camp which convinced him he had punished blacks involved in the murder of Cobb’s shepherds on the Gwydir, a crime for which hundreds had already been killed. Back at Cobb’s head station, Nunn boasted to the appalled squatter of ‘popping off with his holster pistols the Blacks whenever one appeared from behind a tree’.

Again, this foreshadows how things will go. Where killings had to be accounted for, the commanding office would find or fabricate some dubious evidence to justify it. When Gipps presented Nunn’s account of the massacre to his Legislative Council, according to Marr he knew it to be a whitewash, but nothing more seems to have been done about it. Nunn’s boast was reported years later, according to a note, by Lancelot Threlkeld, another of the book’s settler heroes. Again and again, we see private boasting recorded in memoirs or letter, as opposed to public justifications.

I kept thinking of the last line of Bob Dylan’s ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’: ‘Bury the rag deep in your face, for now’s the time for your tears.’

After the first group’s meeting, Friday night: For this group, we had ambitiously agreed to read and discuss two books, Killing for Country and Debra Dank’s We Come with this Place. I wrote about Debra Dank’s book a while ago, here.

There were five of us. Only two had read all of Killing for Country. Of the others one said she gave up after 10 or so pages because she wasn’t interested in the wool industry and early colonial politics, another read about the same and decided she needed to read something more relevant to her life plans, and the third is still reading it, though she’s suspicious of it because she’s also rereading solid works of history like Heather Goodall’s From Invasion to Embassy and Grace Karskens’s The Colony.

All the same, once the slackers had been duly reprimanded (not by me, I hasten to note), we had a terrific conversation. While acknowledging the huge amount of work that went into the book, and that it had opened her eyes to a history that just hasn’t been told, the other completer said she found it unsatisfactory: leaping from place to place with maps that didn’t always help, likewise leaping from character to character, lacking a solid analytical context. She and the history-reader saw as bugs the things that I was content to note as mildly inconvenient features that resulted from the basic decision to follow the careers of particular David-Marr-related individuals.

There was some discussion of David Marr’s decision not to include Indigenous voices. I think he gave a good account of that in his final chapter:

This is a white man’s view of this history. I’ve drawn on rich Indigenous resources to write the bloody tale of Mr Jones and the Uhrs, but I found it was not my place to give the Aboriginal view of this tangled history. I asked Lyndall Ryan, veteran of so many academic battles on the frontier, which Indigenous scholars I should read. Indigenous scholars, she said, research particular incidents in their country. ‘But they don’t work on the frontier wars. The topic is whitefella business.’ An Indigenous colleague I’ve known for years put it this way: ‘You mob wrote down the colonial records, the diaries and newspapers. You do the work. You tell that story. It’s your story.’

(Page 409)

Others still felt that there was a glaring absence in the book.

The non-readers were appropriately contrite and asked productive questions.

We had all read and loved We Come With This Place. The mood lifted as we discussed it. Smiles came back to our faces, and we found ourselves flipping through the book to quote bits.

After the second group’s meeting, Tuesday night: This is my much loved, long-running, all male group (I’m the only man in the other).

I had a runny nose on Saturday night and a positive RAT on Sunday morning, so was stuffed with antivirals on Tuesday and couldn’t be there for this discussion. In the WhatsApp chat ahead of time, one man said he couldn’t read the book: ‘It was too brutal and depressing.’ Another sent us a lnk to The Australia Institute’s webinar with David Marr. After the even the WhatsApp reports said there was at least an hour’s worth of animated discussion.

I guess I’ll watch the webinar when I’ve had a little lie-down.