Jennifer Maiden, The China Shelf: New Poems (Quemar Press 2024)

Jennifer Maiden and her daughter Katharine Margot Toohey, publisher of Quemar Press, have been doing a literary highwire act for years: a cover image of a future book and its general theme are announced early in the year, sample poems uploaded as they are written, and then the book appears at the beginning of January the next year. They did it again in 2023.

Beginning early last year, Quemar Press uploaded an image of the cover of The China Shelf and 11 ‘sample poems’. Each of the poems was freshly written when uploaded, and very much of its moment: July’s poem referred to talk of Julian Assange at an Ausmin Conference (press report here, poem here); August’s to the US’s alleged demand that Imran Khan be removed as PM of Pakistan (press report here, poem here); and so on. We were seeing the project being created in real time – its contents determined by world events, and the collection as a whole relating thematically to Jennifer Maiden’s china shelf with its figurines that range from cute ceramic cats to model nuclear submarines. Now we have the book itself.

The poems in The China Shelf continue in the mode Jennifer Maiden has made her own: conversational, with unobtrusively musical half-rhymes; featuring fictional or historical characters freshly woken up (most of them familiar from earlier Maiden collections); taking issue with political leaders, mostly from the Labor or Democratic Party side of politics; taking controversial stands on many issues, including sympathy for Putin in his invasion of Ukraine (though there’s not so much that in this collection); making surprising connections between people and events; reflecting on her creative process and arguing with critics and publishers; sometimes gossipy, with flashes of glorious lyricism. You can read the samples at this link.

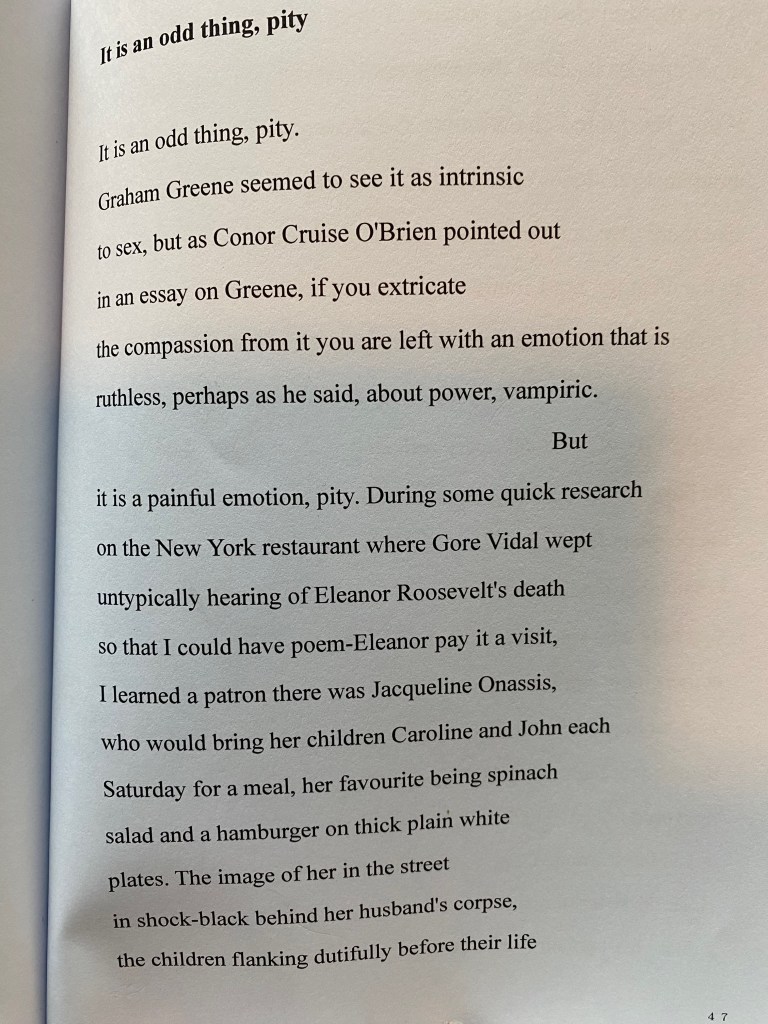

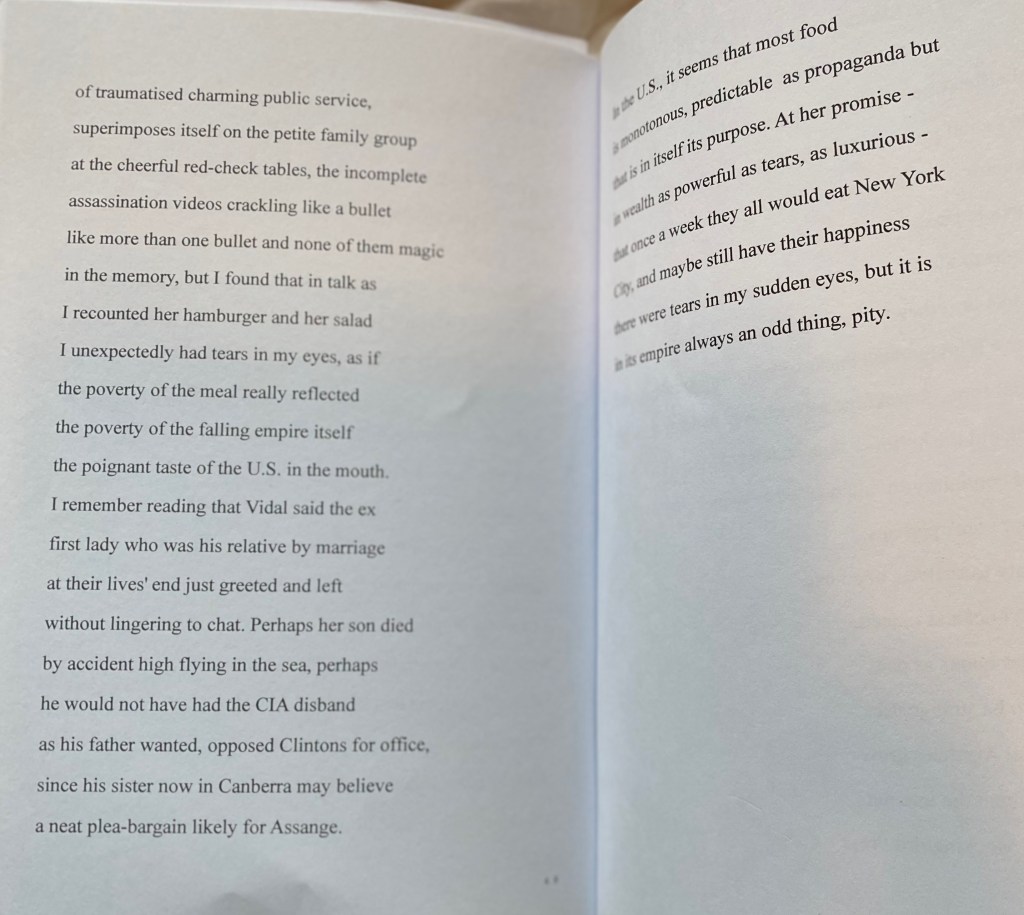

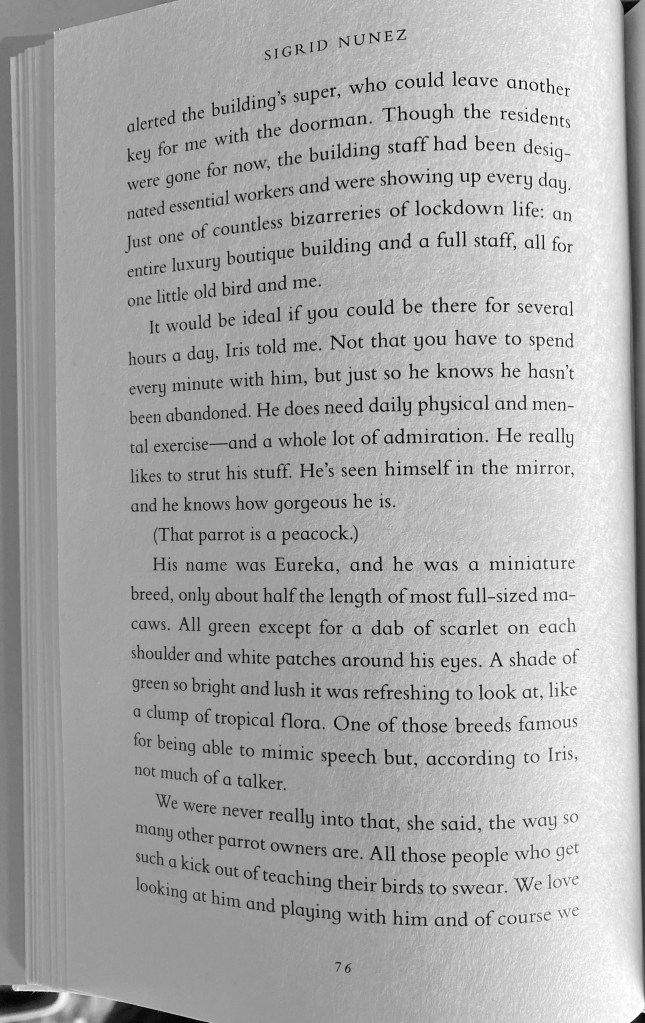

There’s no page 76 (the page I usually blog about, because it’s my age). My fallback position is page 47 (my birth year). Because the poem that begins there is three pages long, I’m bending my rule to talk about pages 47–49. I apologise in advance if the discussion is a bit laboured – the poem is not.

First, here are phone photos, which with any luck will look OK on your device. Click to enlarge.

I probably wouldn’t have chosen ‘It is an odd thing, pity’ to discuss – it doesn’t feature the china shelf, or begin with a character waking up, or reflect on the Australian poetry scene – but it turns out that serendipity is a wonderful thing, and the poem rewards a closer look.

A Study Notes synopsis might go something like this: The poet, while researching a restaurant that is the setting for another poem, discovers that Jackie Onassis took her two children there regularly for hamburgers and salad. She surprises herself by shedding a tear when telling someone about these modest family meals. The poem probes the meaning of those tears.

If you wanted a straightforward enactment of the Study Notes synopsis, you’d be annoyed by the amount of extra clutter in the poem. But (of course) that clutter is what makes the poem interesting.

It starts with a move characteristic of Maiden, an invocation of another writer, in this case Graham Greene, and Conor Cruise O’Brien commenting on him:

It is an odd thing, pity

It is an odd thing, pity.

Graham Greene seemed to see it as intrinsic

to sex, but as Conor Cruise O'Brien pointed out

in an essay on Greene, if you extricate

the compassion from it you are left with an emotion that is

ruthless, perhaps as he said, about power, vampiric.

It’s a long time since I’ve read any Graham Greene, and I have only a vague idea who Conor Cruise O’Brien is. (Change the names, and I could write that sentence about many Maiden poems – not a criticism of her, but an acknowledgement of my own ignorance.) I did a quick internet search, mainly hoping to read a less cryptic version of what Greene and O’Brien said. The search was fruitless, so I’m left where I might have been content to be anyway, finding my own way with the poem.

it turns out that the poem doesn’t need a reader to grasp the paradox of pity as a ruthless emotion, understand the distinction between compassion and pity, or know anything specific about Graham Greene and sex. Greene and O’Brien now depart and are heard no more. The poem has invoked them as a way of announcing that pity is seen as problematic more widely than in this poem. The lines are a kind of paradoxical preface that one expects the rest of the poem to elucidate, or perhaps bounce off.

And bounce it does, with the word ‘But’ on the extreme right on the next line:

______________ __________________________But

it is a painful emotion, pity.

Echoing the opening line, this takes control back from Greene and O’Brien, not so much disagreeing with their thesis as adding another dimension. Pity is not just an objective ‘thing’ to be discussed, but an ’emotion’ to be felt. It might be odd from a philosophical distance, but as lived experience, it’s painful.

Now the narrative proper begins:

it is a painful emotion, pity. During some quick research

on the New York restaurant where Gore Vidal wept

untypically hearing of Eleanor Roosevelt's death

so that I could have poem-Eleanor pay it a visit,

I learned a patron there was Jacqueline Onassis,

who would bring her children Caroline and John each

Saturday for a meal, her favourite being spinach

salad and a hamburger on thick plain white

plates.

That’s all one sentence. There’s no rhyme scheme in this poem, but it’s interesting to notice the music in these lines, helped among other things by the recurring ch sound at the end of lines: ‘research’, ‘each’, ‘spinach’.

The poem has arrived at its central image: Jacqueline Onassis and her children eating a modest meal. As I imagine you know, Jacqueline Onassis, wife of business magnate Aristotle Onassis, was formerly Jackie Kennedy, wife of President John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated in 1963.

The restaurant, as you probably don’t know, is Mortimer’s, a fashionable burger joint (the subject of a memoir, Mortimer’s: Moments in Time by Robin Baker Leacock (2022)). The poem referred to, ‘Eleanor Roosevelt Woke Up in a New York Burger Bar’, appears earlier in the book and is included in the Quemar Press sampler. Gore Vidal makes regular appearances in Maiden’s poems, mainly because Julian Assange was carrying a book by him when forcibly removed from the Ecuadorian embassy in 2019. Maiden’s poems often refer to each other in this way, and the detail of Gore Vidal weeping ‘untypically’ may be a product of another feature of her poetry: the recurring characters (poem-Eleanor is one, poem-Gore is another) tend to take on a life of their own, and here Gore Vidal insists on being more than a passing name-drop. His tears are the first of three lots in the poem.

Picturing Jacqueline Onassis with her children, Maiden’s mind goes to the assassination and the famous footage of Kennedy’s funeral:

plates. The image of her in the street

in shock-black behind her husband's corpse,

the children flanking dutifully before their life

of traumatised charming public service,

superimposes itself on the petite family group

at the cheerful red-check tables, the incomplete

assassination videos crackling like a bullet

like more than one bullet and none of them magic

in the memory,

‘Shock-black’ demonstrates just how much work a single adjective can do, conjuring up the mood of that famous footage. But it’s now 60 years after the event, and the passage of time adds further superimpositions. The children’s futures are summed up elegantly as lives ‘of traumatised charming public service’. The controversy and conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination (was there more than one shooter? was it a CIA plot?) are thriftily evoked: the videos are incomplete and there may be more than one bullet. (There’s no magic bullet to cure the ills of that moment.)

Now comes another ‘but’, which pulls attention back to the immediate emotional impact, not of the funeral scene, but of the image of the meal:

in the memory, but I found that in talk as

I recounted her hamburger and her salad

I unexpectedly had tears in my eyes,

Earlier, Gore Vidal wept ‘untypically’. Now the poet’s speaker does so ‘unexpectedly’. Gore, waspish observer of the social scene and sharp political commentator, has a moment of straightforward grief. Maiden, intent on creating complex poem-versions of public figures alive, dead and fictional, has a simple emotional response. You or I might have left it at that – it may be unexpected, but surely it’s not weird to be moved by the image of a recent widow and her orphaned children having a quiet meal: ‘It is a painful emotion, pity.’ But things are rarely simple in a Jennifer Maiden poem, and this one twists off in an unexpected direction:

I unexpectedly had tears in my eyes, as if

the poverty of the meal really reflected

the poverty of the falling empire itself

the poignant taste of the U.S. in the mouth.

Rather than reflecting, as a lesser poet might have done, that even in the midst of international political events the suffering of a small family can evoke our empathy, Maiden takes a different tack: even a simple empathetic response can be understood in terms of major political movements. The humble meal, it suggests, reflects something about the humbling of US imperialism.

Not everyone will grasp how US imperialism can be seen as ‘falling’. If anything some would say it’s on the verge of exploding and bringing the rest of us down with it, terrifying rather than poignant. But for the poem ‘the poverty of the falling empire’ is a given, not a point of view to be argued for or needing the reader’s agreement.

We now move on to what lay in the future for that ‘petite family’. Gore Vidal is back, this time as a witness:

I remember reading that Vidal said the ex

first lady who was his relative by marriage

at their lives' end just greeted and left

without lingering to chat. Perhaps her son died

by accident high flying in the sea, perhaps

he would not have had the CIA disband

as his father wanted, opposed Clintons for office,

since his sister now in Canberra may believe

a neat plea-bargain likely for Assange.

The mother became unsociable. The son died in an air crash – with two perhapses reminding us that conspiracy theories also hovered around his death. The daughter is now the US ambassador to Australia. Julian Assange has appeared in many Jennifer Maiden poems, and Caroline’s probable support for ‘a neat plea-bargain’ makes her one of the good guys in Maiden-land.

I don’t understand the ‘since’ in the second-last line there. Again, it feels as if a more detailed argument is being gestured at, but not something to be gone into here – this poem has other fish to fry.

The final lines return to the burger joint:

In the U.S., it seems that most food

is monotonous, predictable as propaganda but

that is in itself its purpose.

In real life, food is probably no more monotonous in the U.S. than anywhere else, but we’re talking about a burger joint – specifically, comfort food in a high-profile burger joint. A crude paraphrase of these lines might be: Propaganda is the McDonalds of the soul. The purpose of monotonous, predictable food is the same as that of comforting, reassuring propaganda: to dull the senses, lower expectations, create a compliant population.

that is in itself its purpose. At her promise –

in wealth as powerful as tears, as luxurious –

that once a week they all would eat New York

City, and maybe still have their happiness

there were tears in my sudden eyes, but it is

in its empire always an odd thing, pity

Without the ‘clutter’ (that is, without the things that make the poem interesting), this could be paraphrased: ‘It was her promise of this weekly routine meal together, which might enable the three of them to be happy in spite of Kennedy’s death, that brought tears to my eyes.’ That is, the poem’s speaker, aware of the terrible ordeal that this family has gone through and of so much that is yet to come, sees this attempt at reassurance as pitiable.

The line that gives me pause is ‘in wealth as powerful as tears, as luxurious’. The line’s music works beautifully, ‘luxurious’ rhyming with ‘purpose’ and promise’ in the previous line, ‘powerful’ also resonating with ‘promise’, and ‘tears’ and luxurious’ resounding with a kind of end alliteration. Its meaning is not immediately clear. On the one hand, perhaps Onassis’ wealth, power and luxury are enough to outweigh her pain. On the other hand, her promise is made from a position of privilege that makes any tears she sheds a luxury. (I don’t want to make too much of ‘eat New York / City’ as suggesting that the Kennedy’s, specifically these three, were great devourers, as it is may be a typo – though even as a typo it would be a kind of Freudian slip.) In the poem, however, the person who sheds tears isn’t Onassis, but the poem’s speaker, demonstrating that whatever you/she might think about people of power, wealth and privilege, you can surprise yourself by the feeling a straightforward sympathy for them.

The final line brings us back to the start. Yes, pity is complex, but unless I’ve completely missed the point, this particular example is not sexy, ruthless of vampiric. We may even surprise ourselves by weeping tears of pity for those whom we might see as possessing those qualities. I love the phrase ‘in its empire’: pity, which I take to be the way we as humans spontaneous care about each other, has its own empire, which does not bow to any ideology.