Sue from Whispering Gums respectfully suggested that I not try to squeeze a whole day of the SWF into one blog post. Day Two’s post was a marathon to write but hadn’t realised it was imposing a burden on readers as well. So, even though none of my subsequent days were as loaded as Friday, I’m taking her advice. Here are the first two of Saturday’s three sessions.

Saturday 25 May

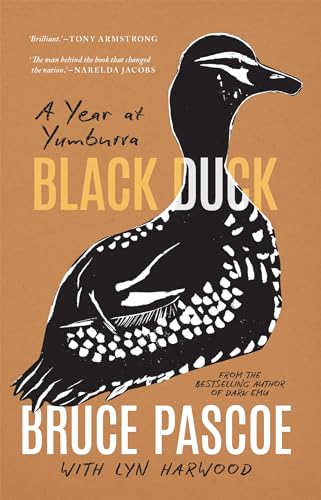

1 pm: Bruce Pascoe and Lyn Harwood: Black Duck: A Year at Yumburra

This session is a variation on my standard session: two people talking about one book with one other person.

Bruce Pascoe’s most recent book, Black Duck: A Year at Yumburra, shares authorship with his wife, Lyn Harwood. They chatted with veteran journalist Kerry O’Brien about their project at Yumburra, their relationship, the devastating bushfires of 2019–2020, the impact of Pascoe’s book Dark Emu (my blog post here) and the subsequent backlash, and related matters.

After Dark Emu‘s success, Pascoe decided to put his newfound wealth to good use. Aware of a new enthusiasm for native foods – he didn’t use the phrase ‘bush tucker’ – he was concerned that there was little consideration for benefit to Aboriginal people. So he bought the farm at Yumburra to grow food, employ Aboriginal people and make a declaration of Aboriginal sovereignty.

I didn’t get a clear sense of the book Black Duck, but I gather it’s in effect a diary of a year spent at the farm. Lyn Harwood spoke eloquently about the effect of writing things down. You spend most of the time dealing with things as they arise, just doing the work. it’s not until you stop to write it down that life, ‘especially the sensuousness of life’, is properly imprinted. The process of writing the diaries was a way of attending to what was happening on the land – not just the work, but the effects of the changing seasons.

Kerry O’Brien, excellent journalist that he is, gave Pascoe opportunities to address the various fronts on which he has been attacked.

On this subject of his Aboriginal identity, he described some of the cultural work he had to do. There was an occasion when he said something stupid and an Aunty said, ‘You know nothing. You know nothing. You go back to the library.’ She may have been speaking metaphorically, but he took her literally and went back to the library to research the history he had got wrong. His Aboriginal identity is contentious among some people, but not among his local mob. ‘I have a very small connection and I admit to it,’ he said. But I identify with it.’ These questions of identity, he said, are a distraction from what matters: when he offered a non-Aboriginal shopkeeper some vanilla lily bulbs he had grown on the farm, her first response was not to consider the possibilities being offered to her but to as, ‘What proportion Aboriginal are you?’ The gasps from the audience demonstrated that he had made his point.

On the validity of the argument of Black Emu, he cited the work of archaeologist Michael Westaway: with the assistance of the Gorringe family, he set out to test Dark Emu‘s hypothesis about pre-settlement history in Mithaka country in Queensland, and found ample evidence that here had been substantial ‘town life’ there.

My main takeaway from the session was the reiteration of the key message of Dark Emu: Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people have a shared history. One of Pascoe’s mentors, commenting on Dark Emu, said: ‘If I’m going to keep my culture, I have to give it away.’ If non-Aboriginal people aren’t invited in, they (we) remain angry, unsettled spirits. Over millennia, Aboriginal people had a continent where there were no wars over land: each group has responsibility for their own Country. If your neighbour is weak or in trouble, you can help them out, but you cannot take their land.

Pascoe says that, in spite of the Referendum result, he thinks there’s a big change coming, as people come to realise that the future of Aboriginal people is the future of all Australians. Just as his work at Yuburra is offering possibilities for agriculture, a future is being offered to us in many ways as a gift with an embrace.

3 pm: Bringing the Past to Life

Ah! A proper panel: three people talking about one book each to one other person. The writers were Francesca de Tores (Saltblood), Mirandi Riwoe (Sunbirds) and Abraham Verghese (The Covenant of Water). Abraham Verghese had Covid, so appeared on a giant screen behind the others. The fourth person was Kate Evans of the ABC’s Bookshelf. The session was most satisfactory.

I hadn’t read any of the books, though I had read Mirandi Riwoe’s earlier novel Stone Sky Gold Mountain (link is to my blog post).

Kate Evans ruled with a rod of iron, asking a series of questions, and making sure that the writers had roughly equal amount of time in response to each question: setting, characters, plots, dark matter. No butting in or dominating. (I’m embarrassed to say it, but perhaps it helped that the only man was a person of colour.) As a result, even without being read to, we got a good sense of each of the novels.

Saltblood is set in the Caribbean in the 1720s, towards the end of the golden age of piracy, and is based on the historical women Mary Read and Anne Bonny. De Tores said that she was happy to call Mary Read a woman, although her gender identity was complex – she was raised as a boy and spent most of her life as a pirate dressed as a man. There’s an early book about pirates – I didn’t catch its name but it is evidently the main if not the only source of everything we think we know about pirates from that time. In that book, the lurid potential of women pirates was played up, and in its second edition the illustrations showed them swashbuckling with breasts exposed. Saltblood sounds like fun, but focuses on more interesting things than bare boobs.

Sunbirds features an Indonesian family in Western Java in 1941. The family and their servants deal with issues related to Dutch colonisation and nationalist resistance, and imminent invasion by Japan. A Dutch pilot is wooing the daughter of the family, who is torn between loyalty to her family and the attractions of life in the Netherlands. Meanwhile a servant of the family has a brother who is part of the resistance. Miranda Riwoe described herself as Eurasian, and so drawn to the plight of the daughter.

The Covenant of Water draws on Abraham Verghese’s own family background in Kerala (he was born and raised in South Arica, but Kerala was always in the background). The story covers three generations in the first half of the 20th century. There is a child bride. Verghese said he was playing against stereotype by giving her a happy marriage. He is a doctor specialising in infectious disease (he pointed out the irony that he was attending on screen because of a coronavirus), and the novel pays attention to advances made in medical science in the period it covers.

So, three interesting books for the TBR shelf.