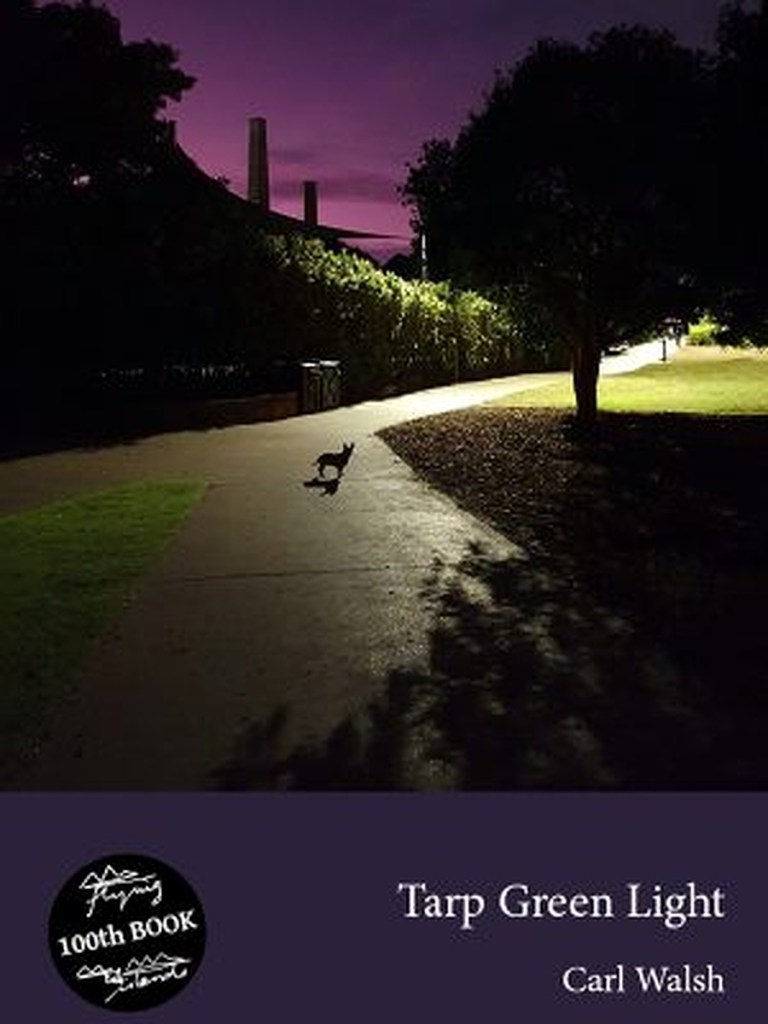

Carl Walsh, Tarp Green Light (Flying Island Books 2023)

Of recent years the emerging Artist and I have travelled north for a couple of weeks each winter. In last year’s fortnight on Yunbenun (Magnetic Island) I read and subsequently blogged about nine books, eight of which were in Flying Island’s Pocket Poets series.

This year we have come further north, and I’ve read a lot less. Tarp Green Light is the first of four Pocket Poets I’ve read.

The Note on the Author tells us:

Originally a tradie, Carl snuck into uni in his mid-twenties, after two years volunteering in PNG. He’s almost always written poetry – some poems in this book had their genesis in notebooks while backpacking in 1997.

Those backpacking notebooks have borne wonderful fruit. There are fine poems on other subjects – Linnaean categories, the Old Norse alphabet (I think), childhood memories, family history, and more. But it’s the poems that evoke particular places that create the strongest impression. The places include Papua New Guinea, Ireland, rural Australia, a number of European countries, and Japan.

The book’s title comes from one of the PNG poems, ‘Sepik Wara’. The poem is hard to quote from, as it’s laid out with text on either side of a broad winding river of white space, but here’s an attempt:

_________________________ _____________ we eye

rush of black clouds____________ __ _ pooling

in the sky; unfold ______________plastic tarps

to array over_______________________ our heads

as rain sheets________________ down we breathe

the close_______________ air and laugh at each

other__________________ in the tarp green light

At least one poem, ‘Idiot Fruit’, visits the Daintree, where I have recently spent a day:

Is it cassowary plums that lay

as blue/grey eggs on the ground?

My blogging practice is to focus on page 77 (at least until I turn 78). In books like this, the practice saves me the impossible task of choosing one poem to represent them all. ‘Niseko miso’, on this book’s page 77, is one of the very few prose poems in the book, but in other ways is a fine example of how Carl Walsh can evoke a place::

Niseko miso

The cloudiness of my miso is reflected in

afternoon sky with dark seaweed stretches of

kombu cloud and strips of white tofu. But this sky

is perforated with peaks. Active in their inactivity

– three thousand years just a nap. How old I

am in their years? My head hurts at the maths.

Perhaps I should get Isabelle to calculate it? Some

are wild for ten thousand years. Even resting,

prone to throwing unexpected parties. I glance

at Mt Yōtei, its dark bulk everywhere. Hope it's

content with its sleeping. That Kagu-tsuchi-no-

kami, the fire-spirit, is happy. I stir my miso – and

the clouds burst with rain.

Like many travel poems, this becomes more enjoyable when you know something about the places it names. A quick bit of browsing told me that Niseko is a ski resort area in Hokkaido; kombu is the kind of seaweed you might find floating in a bowl of miso soup; Mt Yōtei is a volcano, one of the hundred famous mountains of Japan, and popular for backcountry skiing expeditions; and Kagu-tsuchi-no-kami is, as the poem implies, a fire spirit whose rages are to be feared. Mt Yōtei last erupted about 3000 years ago but it is still active.

The poem deftly conjures up a situation: the speaker is drinking miso soup one afternoon in the foothills of Mt Yōtei, probably at a resort of some kind (his mind goes to wild parties as a synonym for volcanic eruption). He may be alone while drinking soup and composing the poem, but he has a female companion, Isabelle, who is probably travelling with him, certainly within easy communication distance.

The speaker idly/playfully notices a similarity between the appearance of the sky and that of his soup: clouds and seaweed allow sky and soup to be synonyms for each other.

Then there’s a but, a word I’m coming to love in poetry as signifying a turn of some kind. Here the speaker notices the major flaw in his synonym: the soup has no equivalent to the mountain peaks that pierce the clouds. The mountains dominate the rest of the poem, prompting thoughts about geological time. The tone is still playful – volcanic activity is described as wild partying, prolonged or brief and unexpected – but there are quiet hints of awe in the presence of the sublime.

In the two sentences before the last one, another dimension of the place of the poem comes into play. These mountains have had stories told about them for millennia. The speaker acknowledges this, by naming the fire spirit Kagu-tsuchi-no-kami, at the same time expressing anxiety about a potential eruption. (Maybe it’s just me but that seems to be a very Australian response, given how very extinct our volcanoes seem to be.)

Then in the last sentence, the poem comes down to earth, and attention returns to the soup and the clouds. There’s a hint of sympathetic magic – did stirring the soup make the rain come? – but the main effect is to pull back from vast, fearsome, mythological thoughts to the present moment, the place where the poem started.

I read this book near the mountains of Yidinji land and finished writing the blog post on Gadigal–Wangal land, where the sky is brilliant blue and the wind is chill. I acknowledge the Elders past and present of both peoples.