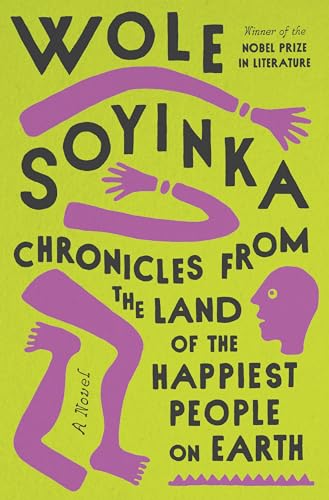

Wole Soyinka, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (©2020, Penguin Random House 2021)

Before the meeting: This is a strange book. It’s a satire set in contemporary Nigeria. With Boko Haram atrocities in the immediate background, the country is rife with corruption. I’m pretty sure that if I knew more about Nigeria’s history and its current politics the book would reveal more of itself to me as a devastating, possibly despairing denunciation of Soyinka’s homeland. As it was, I enjoyed it pretty much as a child would enjoy Gulliver’s Travels – as a fantastical tale. I’m sorry to say, though, that I enjoyed it a lot less than I enjoyed the story of Lilliput as a child.

Almost half the book is taken up with setting the scene in magisterial, ironic tones. There’s a charlatan religious leader, a deeply venal and media-savvy Prime Minister, an awful lot of sarcastic hoptedoodle about national festivals and awards. It takes a long time for a central narrative thread to become clear. (Arguably, the over-all shape isn’t revealed until the last page, so what follows is possibly a spoiler of the first magnitude.) Four young Nigerian men form a strong bond when at university in Europe, agreeing that they will each contribute in a major way to their homeland. They become respectively a doctor, an engineer, a financial wizard and a public relations genius. In the book’s present time, one has gone missing, one runs foul of the government and becomes inexplicably catatonic, one has been nominated to a prestigious position in the UN, and the fourth, who I think of as the book’s central character, is a surgeon whose work patching up the survivors of Boko Haram attacks has earned him one of the country’s top honours.

The rubber hits the road at last when the surgeon discovers a monstrous commercial-culinary trade in human body parts, and the narrative finally develops a forward momentum as he and his engineer friend pit themselves against the shadowy figures behind the trade.

But just as that narrative seems to be getting somewhere, the book swerves off into interminable machinations to do with a bombing, and questions of transporting a body between Austria and Nigeria. The main story is finally resolved in an ultra-perfunctory way, with a lot of loose threads left hanging. There’s a ‘surprise’ revelation on the last page that is about as surprising as having hot water come out of a tap marked H.

The story is told with tremendous gusto, but for much of it the writer seems to care less about telling it than with having angry, satirical fun. I found myself thinking of Edward Said’s posthumously published essay, On Late Style, which we read in the Book Group a while ago (link here). He wrote of the artists who create in the late style:

The one thing that is difficult to find in their work is embarrassment, even though they are egregiously self-confident and supreme technicians. It is as if having achieved age, they want none of its supposed serenity or maturity, or any of its amiability or official ingratiation. Yet in none of them is mortality denied or evaded, but keeps coming back as the theme of death which undermines and strangely elevates their uses of language and the aesthetic.

This book is supremely unembarrassed by its own excesses and absurdities. It certainly doesn’t aspire to serenity or seek attempt to ingratiate itself with authorities, or with readers. And it is full of mortality.

At page 77*, we’re still being given the general set-up. It’s part of the engineer’s back-story, explaining how he ‘succumbed’ and agreed to work for the government:

It did not take too long to discover – with some chagrin, he would reveal to his ‘twin’, the surgeon Kighare Menka – that there was a strong work ethic in control, indeed a pervasive hands-on ethic, near identical to both theirs, with unintended literalism, just a slight slant – a prime ministerial finger in every pie!

His friendship with the surgeon Kighare Menka is the heart of the book. Here it’s invoked so that we know both men share a perspective on the Prime Minister’s corruption, and that they share an enjoyment of the ponderous wordplay that pervades the book.

The next paragraph is a good example of the narrative style. Bisoye is the engineer’s wife:

Only the twenty-million-dollar question remained: How long would he last? Thus came the pact with Bisoye – first three months, I’ll stick it out, no matter what. Agreed? After that, a choice of his single-malt whisky, always a different brand, for every month survived, plus a night out followed by a bed in, no holds barred. The nation never knew how much it owed to the blissful athleticism of the couple, and Duyole did come close to earning a full case of Islay malt, Collector’s Reserve – just one bottle short of a full case. In the display cabinet he conspicuously left a gap in the row of twelve, a silent accusation of Bisoye’s ungenerous spirit. Was it his fault he completed the task so far ahead of time?

This mock-pompous style characterises most of the narrative. A man of integrity decides to do research for a corrupt government, and to report honestly on what he finds. But he’s a man with a sense of humour and a zest for life. Like him, the narrative refuses to be drawn into hand-wringing over the corruption. It barely gets to the specifics of that corruption – saving its fire for the (hopefully) imaginary trade in human flesh. It is happy to assume the reader doesn’t need details of the realistic stuff and gives us instead the ‘blissful athleticism’ of our heroes, the opposition.

While that paragraph may fill out the engineer’s character a little, one can’t help but feel that it’s just there because the author was having a good time. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. On the contrary. But I’m not surprised to learn from the WhatsApp conversation before the meeting that most people failed to persevere to the moment when the story proper gets started.

After the meeting: There were eight of us, and we met in a pub in Balmain. Two of us had read the whole book. All but one of the others had no intention of finishing, most having given up after a hundred pages or so.

Interestingly, the person who had read about a third was the book’s keenest supporter. I don’t take notes, and I have a terrible memory, but he said something like, ‘I was irritated, intrigued, amused, horrified, perplexed, enlightened, admiring. I kept seeing parallels with news from the US in the bizarre corruption, and the dominance of bogus religion. The back story of the religious charlatan fascinated me, and I want to know what becomes of him.’

I think he was on the cusp of the moment when the character who fascinated him pretty much drops out of the story, to make a functional comeback very late in the piece. He had barely even met the surgeon Kighare. But it was excellent to be reminded that up to a certain point you think you’re reading a book where a number of strands are kind of coming together.

Someone had read that Wole Soyinka wrote the book during Covid lockdowns in two stretches of 32 days. Maybe that was just a first draft.

Someone said that they kept wondering if they’d missed something, as for instance when a character last seen entering a meeting turns up a couple of chapters later in a catatonic state, but the writing was so elliptical that they couldn’t be bothered to go back to check if there was some explanation. (No one could remember if we are ever told what happened to him. I suspect the author made a mental note to go back and flesh it out, and then forgot about it.) I think that means it’s a book that asks a lot of the reader at the sentence level, without generally offering much in return.

Someone said it might have been better in the original Nigerian. I think his point remains valid even though the book was written in Nigeria’s official language, which is English. Nigerian writer Ben Okri wrote a review for the Guardian, which I’ve found since our meeting (link here). Given how negative we all were about the book, it’s only fair that I quote from that review (though I must not that ben Okri gets a number of key plot points wrong in this review):

There are many things to remark upon in this Vesuvius of a novel, not least its brutal excoriation of a nation in moral free fall. The wonder is how Soyinka managed to formulate a tale that can carry the weight of all that chaos. With asides that are polemics, facilitated with a style that is over-ripe, its flaws are plentiful, its storytelling wayward, but the incandescence of its achievement makes these quibbles inconsequential.

Our conversation turned to other, happier things: the recent local council elections and the pleasure a couple of us had had in helping a young person vote for the first time; parenthood after 40 years; the relationship of the Bauhaus to the Arts and Crafts movement; another book group where they don’t set a date until everyone has read the book (shudders all round!); a spectacular alcoholic episode from the life of Mary McKillop (now a saint); the unmarked site of Hitler’s bunker; Rugby League (the Roosters, and the Jets at Henson Park); some swapping of notes about streaming shows. The food was excellent, though the emerging Artist could teach the pub a thing or two about caponata.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal. I acknowledge Elders of those Nations past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this beautiful land.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 77.