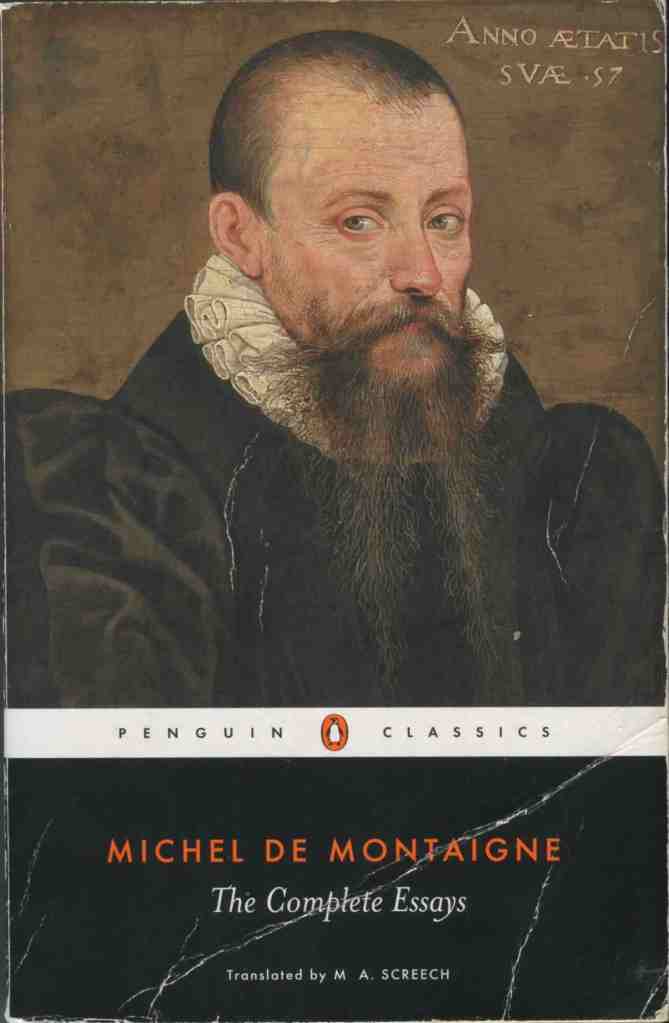

Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays (Penguin Classics 1991, translated by M. A. Screech)

– part way through Book 2, essay 40, ‘On the resemblance of children to their fathers’ to part way through Book 3, essay 5, ‘On Some lines from Virgil’

Montaigne’s essays become even more interesting as he ages. By Book 3, he writes about his chronic pain from ‘the stone’ and, especially in the innocuously titled ‘On some lines from Virgil’, he does some spectacular writing about sexual politics.

I expect that whole books have been written about Montaigne and sex. I won’t try to untangle any of it here. I’ll just quote the paragraph from today’s reading that has given my poem its opening line. (For those who came in late, this November I’m writing at least 14 fourteen line poems, the first line of each coming from something I’ve heard or read that day.) The paragraph will give you just a glimpse of the complexity of Montaigne’s thought:

We do not weigh the vices fairly in our estimation. Both men and women are capable of hundreds of kinds of corrupt activities more damaging than lasciviousness and more disnatured. But we make things into vices and weigh them not according to their nature but our self-interest: that is why they take on so many unfair forms. The ferocity of men’s decrees about lasciviousness makes the devotion of women to it more vicious and ferocious than its characteristics warrant, and engages it in consequences which are worse than their cause.

I think he’s saying that making sexual behaviour a major criterion for a woman’s reputation is wrong; men make the rules that condemn women’s ‘immorality’; and the punishments are much worse than the so-called crimes. Further on in the essay he says that social expectations on women to be chaste are an intolerable burden.

I don’t know if he is putting a proto-feminist case, or arguing deviously that women should be more sexually available to men. Or both. Either way, it’s fascinating to have a voice from a very different epoch wrestling with questions that aren’t exactly resolved today.

But before I leave Montaigne for my own versification, I can’t resist quoting the final paragraph from Book 2, which follows some strong opinions about the medical profession, and rings out like a beacon of rationality for our times:

I do not loathe ideas which go against my own. I am so far from shying away when others’ judgements clash with mine … that, on the contrary, just as the most general style followed by Nature is variety – even more in minds than in bodies, since minds are of a more malleable substance capable of accepting more forms – I find it much rarer to see our humours and purposes coincide. In the whole world there has never been two identical opinions, any more than two identical hairs or seeds. Their most universal characteristic is diversity.

Yay Montaigne!

But on with my verse, which takes the phrase somewhere else altogether – and you can probably see the point when news from the USA knocked the poem off its tracks:

November verse 4: We do not weigh the vices fairly

We do not weigh the vices fairly,

thumb the scales to suit our whim:

I exaggerate, quite rarely –

you tell fibs – but look at him!

His lies destroy the trust that binds us,

lead us where no truth can find us.

Crowds have wisdom, mobs can rule,

electorates can play the fool.

He's murderous and self-regarding,

incoherent, vile, inane.

He once could boast a showman's brain,

but principles are for discarding.

Lord of Misrule, theatre's Vice:

How could you choose him once, then twice?

This blog post was written on Gadigal-Wangal land, where the tiny lizards are enjoying the beginning of hot weather, and jacarandas are the land’s most spectacular guests. I acknowledge the Elders past, present and emerging of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation.