Josh Tuininga, We Are Not Strangers (Abrams Comicarts 2023)

In December 1941, about 127,000 Japanese Americans lived in the continental USA. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war on Japan, about 120,000 of them, of whom about two-thirds were U.S. citizens, were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in concentration camps.

This is not a secret history. In The Karate Kid, the young boy comes across references to the deaths of Mr Miyagi’s wife and child in a camp. Star Trek actor George Takei famously spent a number of years in one of the camps as a child, as told in the documentary To Be Takei (2014) and in They Called Us Enemy, a comic he co-wrote that was published in 2019. David Guterson’s novel Snow Falling on Cedars (1994) and the Scott Hicks film made from it refer to the incarcerations. (There are more examples on Wikipedia – I’ve just mentioned the ones that ring a bell for me.) Various presidents have expressed regret over the episode.

Josh Tuiininga’s comic comes at the subject as it played out in Seattle, from the point of view of Sephardic Jews. It begins in December 1987, with the funeral of Marco, the narrator’s grandfather. The funeral proceeds according to Sephardic tradition, but a lot of people turn up that the narrator has never seen before. Curious, he asks them how they knew his grandfather so well, and the story emerges.

During World War Two, as the Sephardic Jews of Seattle were watching the horrific events unfolding in Germany, they were suddenly confronted by a terrible injustice closer to home, as Japanese friends and neighbours were rounded up, their businesses forcibly closed, and their lives disrupted.

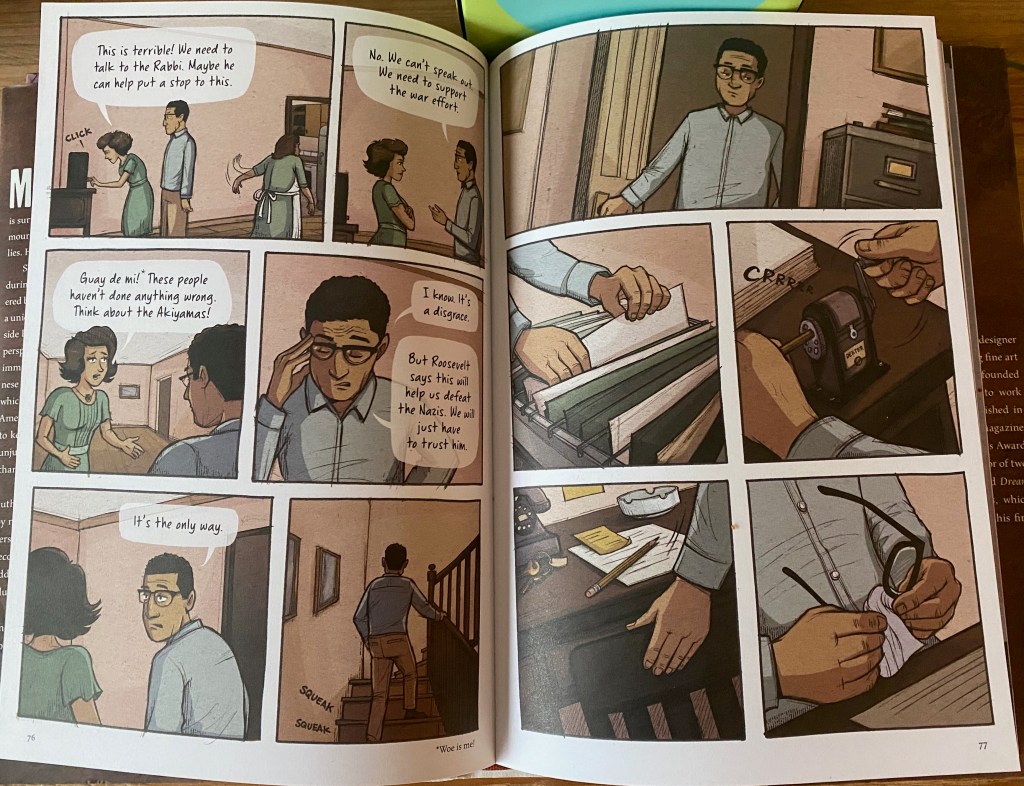

Page 77* marks a turning point. Marco and his family have just heard a radio announcement that ‘the Japanese population in America are potentially dangerous’ and are to be relocated or suffer criminal penalties:

In the first image on this spread, the woman walking away with a dismissive gesture is Marco’s mother, who has successfully escaped Germany and been smuggled into the USA by way of Canada. Her gesture signifies contempt for the edict, which she has just said is like what happened to Jews under the Nazis (not a view the comic necessarily endorses, but it shows the basis for solidarity between Jews and Japanese).

The left-hand page appears to portray Marco and his family as helpless bystanders. Evidently the Japanese American Citizens League recommended compliance for pretty much the reasons that Marco gives here: to resist would be to undermine the war effort. But the wordless right-hand page suggests something else. It is followed by two more wordless pages, a full page drawing of Marco at his desk beneath a clock showing one-thirty, and then a single drawing of a lit window in a dark suburban scape. We don’t now what these images mean precisely, but they remain as a question as the rest of the story unfolds: there’s a Passover sermon at the Synagogue; one of the Japanese children has her white friends turn against her; the Central District of Seattle is filled with remnants of Japanese presence; there are glimpses of life in the camps, and on their closure signs of persistent anti-Japanese sentiment are everywhere.

But it turns out that what Marco was doing in his study that night was working out how he could safeguard his friends’ homes and businesses. When they return home, he gives them envelopes full of rent money, deeds and all that is needed to help restore their lives. And he has done it for as many families as he could manage. Only at his funeral do his own family find out what he has done.

‘Why did he keep it a secret?’ the narrator asks, and over a series of images that show Marco with family and his Japanese fishing friend in 1945, 1953, 1968, 1979 and then (his empty chair at the family table) 1987, the captions read:

Maybe he thought he would get into trouble.

Perhaps he wished he could have done more.

Or, maybe …

… he just wanted to forget all about it …

… and spend his time on more important things.

That last line is a caption between two images, one of Marco as an old man at a family meal, the other (echoing images from early in the book) of him and his Japanese friend fishing together and laughing.

It’s a powerful story, elegantly told in a palettte of mainly warm browns and pale blues. Though a note at the beginning assures us that this is a work of fiction, it also says the story is based on ‘the oral histories of many’.

It’s pure coincidence that I have read this so soon after Yael van der Wouden’s novel The Safekeep. That novel hinges on the loss of property and livelihood by Jews in the Netherlands under the Nazis – so that those who did return from camps found their houses occupied and their personal items now used by strangers. That almost certainly happened to many Japanese-Americans, but this story demonstrates how it could have been different, and that in at least some cases it was different.

It would have been impossible for me to read this book without thinking of North Queensland. My grandfather was a police magistrate. The family story is that because he had learned Italian he was brought back from his posting in Brisbane to supervise the internment of Italians during World War Two. That internment was on a smaller scale – 5000 men were taken from their families to internment camps in New South Wales and South Australia, and at least twice as many were put to work in remote areas building roads and rail, and working in mines. Many were naturalised Australian citizens.For the most part, only the adult men were taken away: the results were devastating for Italian farmers, and families were disrupted.

The ABC ran a story in 2020 marking the 75th anniversary of the end of the War (link here). The excellent Babinda museum tells one man’s story – a man who, characteristically, downplays the difficulties he faced. The official archival records of the internments have been made public for some decades now, but as far as I have been able to tell the many stories – from Innisfail, Ingham, Garradunga, Daradgee, Boogan – have yet to be told.

I wrote this blog post on land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, peoples whose own stories of mistreatment in times of war have yet to be fully told. I acknowledge the Elders past and present who have cared for this land for millennia.