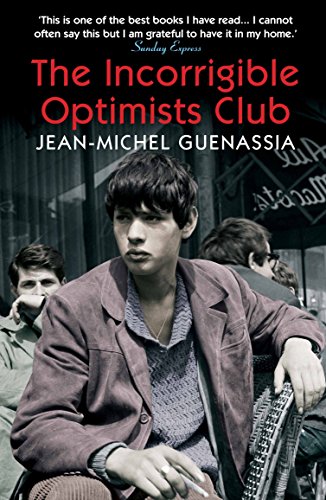

Jean-Michel Guenassia, The Incorrigible Optimists’ Club (2011, translation Euan Cameron 2014)

Before the meeting: The Book Group’s designated chooser defied recent practice and chose a long book – 624 pages in my edition. I doggedly put in the time, and had read the book well before the meeting, only to realise that I was away from home on the night and couldn’t be there.

The club of the title is a group of exiles in 1950s Paris who meet in the back room of a bistro, mostly to play chess but also to share news of their homelands, and to argue fiercely about love, politics and life in general. One of the two main strands of the book is made up of their stories. Mostly they are without ID, even stateless refugees or defectors from the Soviet Union. One has actually been a friend of Stalin’s, who defected for love but remains faithful to the Soviet cause. The rest are dissidents or men (they are all men) who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Jean-Paul Sartre is a member and kind of patron, though after a riveting scene in which he registers news of Camus’ death, he pretty much fades from the narrative.

We see the club and its members through the eyes of Michel Marini, a schoolboy who first visits the cafe to play desktop football (whose French name, ‘baby-foot’, trand). His coming of age story, against the backdrop of the Algerian War of Independence, is the other main narrative strand. Michel befriends Cécile, the girlfriend of his older brother, Frank. Frank bunks off to fight in Algeria, then disappears, only to reappear as a fugitive. Cécile calls Michel ‘little bro’, and neither she nor he realise that he is completely in love with her. Meanwhile, Michel’s parents’ marriage goes through tumultuous times.

It’s never dull, richly political and just as rich in its focus on the storms of adolescence. Yet the blurb describes it as a debut novel. Could this possibly be the work of a young person? I went looking and found that it’s not. According to Wikipedia, Jean-Michel Guenassia is almost as old as me, and was 59 when the book was published. He had in fact previously published one novel, and three TV screenplays and some plays had been produced. The Incorrigible Optimists Club is another example of an overnight sensation that was years in the making.

Euan Cameron’s English version is smooth, lively and engrossing.

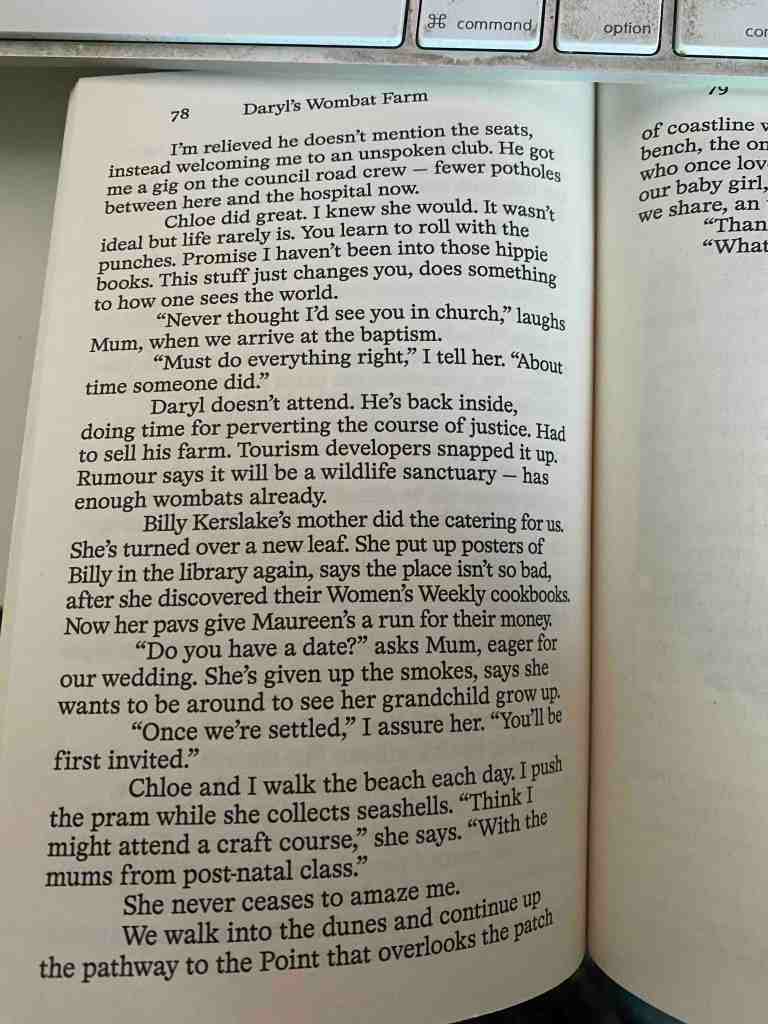

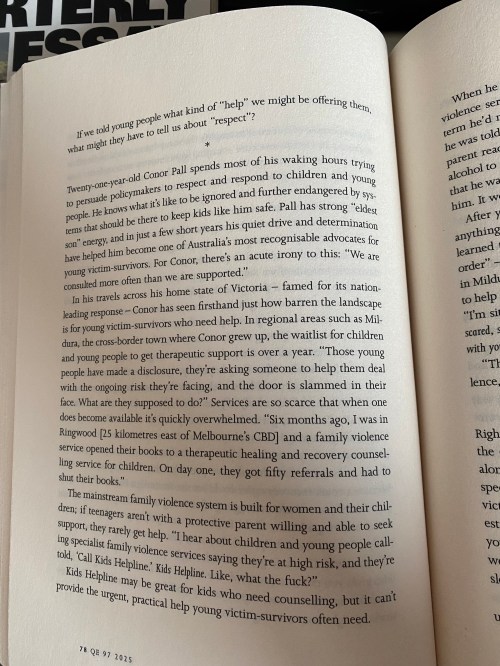

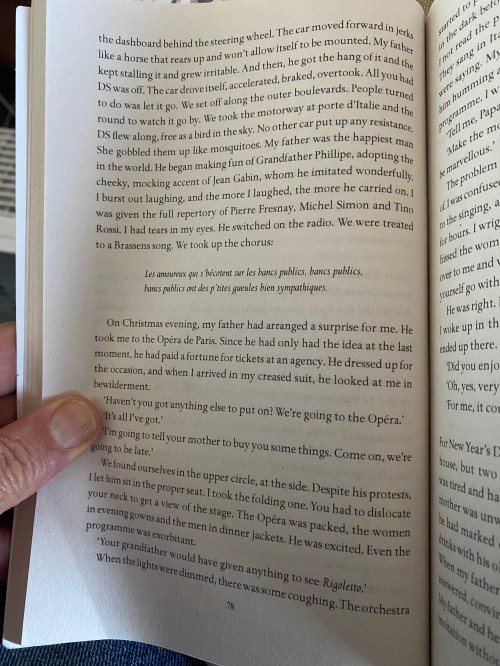

Page 78* highlights elements of the book that didn’t feature in that quick overview. But they’re qualities that are important to the way the book draws the reader into the warm embrace of its imagined time and place.

We’re still getting to know Michel before he becomes involved with the Incorrigible Optimists, before the realities of the Algerian War intrude into his life, before his parents’ relationship becomes fully hostile. His father, a small businessman, has just bought a flash car – a DS 19 – and takes it for a spin with Michel in the passenger seat:

After a rough start, the car behaves like a midlife-crisis dream come true. We’ve been told that Michel’s father loves to impersonate the cool screen actors of the day, and that he is more or less despised by his wife’s upper-class parents, including Grandfather Philippe mentioned here. This paragraph reminds us of that tension, shows him having fun with his son, and at the same time fleshes out the soundtrack of the era. This kind of detail is what brings the narrative alive, even for readers (like me) who have vague to nonexistent knowledge of he singers and actors mentioned:

My father was the happiest man in the world. He began making fun of Grandfather Philippe, adopting the cheeky, mocking accent of Jean Gabin, whom he imitated wonderfully. I burst out laughing, and the more I laughed, the more he carried on. I was given the full repertory of Pierre Fresnay, Michel Simon and Tino Rossi. I had tears in my eyes. He switched on the radio. We were treated to a Brassens song. We took up the chorus:

_ Les amoureux qui s’bécotent sur les bancs publics, bancs publics,

_ bancs publics ont des p’tites gueules bien sympathiques.

Jean Gabin played Maigret in 1958. Pierre Fresnay was the suave Frenchman in La Grande Illusion. Michel Simon was described by Charlie Chaplin as the greatest actor in the world. Tino Rossi, like the others that Michel’s father impersonates, was feted as a film actor who supported the Resistance. Even without all the googling, you can tell that this is a moment when father and son are enjoying each other and loving life, singing together, and celebrating an anti-Fascist strand of French culture.

Here’s a YouTube of George Brassens singing ‘Les amoureux des bancs publiques’. The words don’t really matter, but they translate as ‘The lovers who kiss on public benches, public benches, public benches, have very friendly little mouths.’

Then there’s this:

On Christmas evening, my father had arranged a surprise for me. He took me to the Opéra de Paris. Since he had only had the idea at the las moment, he had paid a fortune for tickets at an agency. He dressed up for the occasion, and when I arrived in my creased suit, he looked at me in bewilderment.

‘Haven’t you got anything else to put on? We’re going to the Opéra.’

“It’s all I’ve got.’

‘I’m going to tell your mother to buy you some things. Come on, we’re going to be late.’

We found ourselves in the upper circle, at the side. Despite his protests, I let him sit in the proper seat. I took the folding one. You had to dislocate your neck to get a view of the stage. The Opéra was packed, the women in evening gowns and the men in dinner jackets. He was excited. Even the programme was exorbitant.

‘Your grandfather would have given anything to see Rigoletto.’

This time Michel doesn’t share his father’s enthusiasm. The tiny incident, especially coming on the heels of the singing together with Georges Brassens, shows us the mutual affecrtion between father and son, as well as the distance that is growing between the generations, both of which become hugely important when the father disapproves of things done by Michel’s brother Frank but makes enormous sacrifices for him.

After the meeting: Sadly, I wasn’t there.

I wrote this blog post on Wulgurukaba land, the luxuriant island of Yunbenun, where cockatoos screech during the day and curlews serenade the night. I acknowledge the Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.