Jennifer Maiden, Ox in Metal: New Poems (Quemar Press 2022)

In her essay, ‘The Political Poem’ in Fishing for Lightning (my review here), Sarah Holland-Batt says that lasting political poems are notoriously difficult to write, in part because of ‘the question of how to transform rage into poetry’. She names three Australian poets who manage to pull it off: Barry Hill, the late JS Harry, and Jennifer Maiden.

In Ox in Metal, her fifth book of new poems from Quemar Press in as many years, Jennifer Maiden pulls off the difficult trick once again.

These lines, from ‘There seems an easiness’ in this book, relate interestingly to Holland-Batt’s generalisation:

is here, but how? A recent ABR review of my last book says I avoid buttonholing the reader by using experienced techniques. I thought: I learned them over half a century, more to make fear bearable for both of us, __________________________________ you and I, not buttonholing, clutching the cliff-edge, turquoise sharp mountains in mist beneath

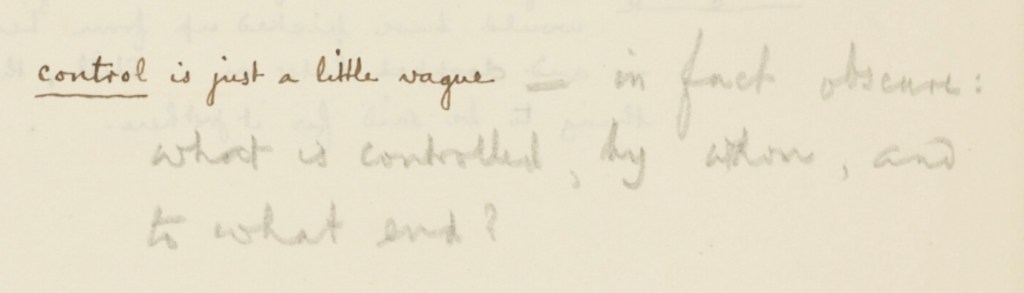

I read buttonholing as meaning the kind of verse that doesn’t manage to stay interesting once its immediate occasion is past, something more than an op-ed piece with added line breaks (not that there’s anything wrong with that). Maiden identifies two things: ‘experienced / techniques’ and an underlying emotional impulse.

The review by Rose Lucas referred to in the poem (at this link) speaks of ‘familiar Maiden strategies’ (rather than techniques) as moderating the ‘pent-up urgency of political imperative’, which isn’t a bad description of what happens in many of the poems.

Chief among Maiden’s strategies/techniques is the use of fictional characters as means to exploring ideas. In a signature opening to a Maiden poem, a historical or literary personage wakes up in the presence of a current political figure who has some connection to him or her: in Ox in Metal, Gore Vidal is paired with Julian Assange who was reading one of his books when arrested; Malcolm Turnbull chats with his relative Angela Lansbury playing Jessica Fletcher; Eleanor Roosevelt broods about Hillary Clinton; and in an interesting variation Maiden herself meets the lunar zodiac’s emblem of 2021, the metal ox. Since their first verse appearance in Friendly Fire (Giramondo 2005), her characters George Jeffries and Clare Collins have turned up in political hotspots in more than 40 poems: here they skype with a deputy leader of the Taliban and Joe Biden (though not in the same poem). There are other creations, including a cute little marsupial named Brookings after the Brookings Institute and the Honourable Carina Monckton, a kind of incarnation of the Carina Galaxy.

A main consequence of all this inventiveness is that when Maiden’s poems assert political views that many would see as contrarian or extreme leftwing*, they don’t harangue readers, or try to persuade us. The lines I quoted above speak, not of the rage that Sarah Holland-Batt sees as needing to be transformed, but of a fear that the poet assumes she shares with her imagined reader. The poetry’s motor isn’t political urgency or the need to vent emotion, but the attempt to make terror bearable, for the reader as well as the poet.

As well as the fictional creations, there are what have been called her weaving poems which bring together seemingly disparate elements – a passing remark by another poet, an item from the headlines, a memory of her daughter’s childhood. These poems are like sculptures created from found objects. An example in Ox in Metal is ‘It can’t be easy, being Tabaqui’, which picks up a quote from Vladimir Putin, finds some Kipling in it, makes connections to a recent biography of Paul Robeson and then-current Australian headline news. It’s a challenging poem to read at this time, as Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine continues to horrify and terrify the world, but here goes.

The opening quote is from Vladimir Putin’s address on 21 April 2021 to the Russian Federal Assembly, a combined gathering of members of the Federation Council (Senators), the State Duma (Parliamentarians), Cabinet ministers, Regional Governors, representatives of selected State Departments, Agencies and the media. In the address as a whole (online here), Putin positions himself as defender of a beleaguered Russia, and we now can see that he was laying the grounds for his invasion of Ukraine nine months later. The claims he was making have been fairly throughly debunked, for example at this link.

Maiden singles out a moment when Putin refers to Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (which you can read at this link). The quotation is almost a found poem in itself, juxtaposing Putin the ruthless imperialist with Kipling, spokesman of the British Empire. I wonder if Maiden considered writing a poem that began ‘Rudyard Kipling woke up in the Kremlin, next to Vladimir Putin’. As a reminder: Tabaqui the jackal is the contemptibly devious offsider to Shere Khan the tiger, deadly enemy of the wolves who adopted Mowgli the book’s hero. Tabaqui’s propensity for rabid rages, mentioned in the poem, comes from Kipling. The Seeonee Pack, named by Maiden but not by Putin, are the wolves, and include Grey Brother, who kills Tabaqui. In the speech, Putin fairly explicitly casts the USA, or perhaps NATO, as Shere Khan.

The context of the quote is less charming, and is not irrelevant to a reading of the poem. Here is the next paragraph:

We really want to maintain good relations with all those engaged in international communication, including, by the way, those with whom we have not been getting along lately, to put it mildly. We really do not want to burn bridges. But if someone mistakes our good intentions for indifference or weakness and intends to burn or even blow up these bridges, they must know that Russia’s response will be asymmetrical, swift and tough.

He was definitely casting himself as the wolf.

Having unsettled the reader by quoting, without disclaimer, one of the nastiest political leaders of our time (it might even have been less unsettling to quote that Serbian butcher who was a Shakespeare scholar), the poem proper begins.

The opening lines make a complete break from Putin, and take a while to get to Kipling:

An Australian biographer of Robeson innocently undermined him with a bulging pocketful of CIA pathologies, summed it up: 'It can't have been easy, being Paul Robeson' but as an alternative to coming up like thunder how easy is it to be a jackal?

This offers a case of a virtuous figure (Paul Robeson) harassed by a smaller one (the biographer) doing the work of a big enemy (the CIA), a version of the Wolf pack–Tabaqui–Shere Khan diagram. ‘Coming up like thunder’, a phrase that seems made for Robeson, comes from a different Kipling work, his poem ‘Mandalay‘. The word ‘innocently’ suggests that the biographer is a useful idiot, doing the CIA’s propaganda work without realising it – but the suggestion hovers that literary biographers (and by extension reviewers, critics and dare I say bloggers) can be like jackals, opportunistic scavengers on other people’s creativity who wittingly or unwittingly serve the interests of political players.

It doesn’t take much research to identify the book in question as Jeff Sparrow’s No Way but This: In Search of Paul Robeson (Scribe 2017). Judging by the reviews, I’m confident that Sparrow would vigorously challenge the assertion that he undermined Robeson, and that Robeson’s ‘pathologies’ are CIA inventions. But we can agree to suspend judgement, and read on.

The word but occurs three times in this poem, each time signalling a pivot: here, it’s a pivot from Robeson to those who would attack him and his ilk.

how easy is it to be a jackal? Pity jackals. All children have been Tabaqui, lying for scraps from any father or mother, living off scraps allowed him by Shere Khan, or the wolves of the Seeonee Pack, and at last killed by Grey Brother. It can't be easy, being Tabaqui.

‘Pity jackals’ shifts the tone: it suggests that it’s important to pay attention to people who curry favour with powerful entities, and do their bidding, even to have sympathy for them. The next line suggests that the roots of such behaviour may lie in the universal childhood experience of dependency, lying as a developmental stage. The next lines slide to a slightly different take, suggesting that children who read The Jungle Book will identify with Tabaqui – will have been him in imagination, similarly to the way we are every character in our dreams.

Now for the only time the verse refers explicitly to Putin’s address:

It can't be easy, being Tabaqui. Putin was perhaps thinking foremost of the Ukraine's build-up of troops, or the put-down violent putsch in Belarus,

There’s no ‘perhaps’ about it (perhaps may well be there for the sale of the almost-rhyme with troops., which in turn chimes with Belarus). Putin was explicit: he was spinning the build-up in Ukraine as a potential attack on Russia, and threatening a response that would be ‘asymmetrical, swift and tough’: in the light of recent events he could have added ‘unprovoked’. This is the most unsettling moment in the poem, as it makes no attempt to distance itself from Putin’s point of view. If written today, reference to ‘the Ukraine’ would signify agreement with Putin that Ukraine is not a separate nation. Is Maiden here playing Tabaqui to Putin’s Shere Khan?

That’s not how I read it. Elsewhere, Maiden often quotes and even portrays sympathetically people whose politics she loathes – Tony Abbott and Donald Trump come to mind. Putin has a point when he says that NATO is hostile to him, even if he doesn’t acknowledge that they may have good reason. But to quote him like this doesn’t imply agreement, and the poem can’t fairly be accused of endorsing military action Putin took long after the poem was written.

The next lines, beginning with the poem’s second but, move away from Putin to the more general phenomenon that is the poem’s real subject:

but jackals are prone to rabies and zigzag insane in a way even feared by the Beloved King:

The first of these lines is from the The Jungle Book‘s account of jackals. There is no Beloved King in that book, at least not by name. The gist is clear enough. Once you unleash Tabaqui, even in a poem, you can’t tell what it will do.

in a way even feared by the Beloved King: Shere Khan might in Australia have wanted famished Morrison to cancel a couple of contracts with China, and academic agreements with Syria or Iran, in puzzled Victoria,

It’s reasonable to take Shere Khan as signifying the USA here, as in Putin’s speech. I found an ABC story about Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s cancelling contracts. It’s dated 22 April 2021 (link here), the day after Putin’s address to the General Assembly. So this example of a Tabaqui doing the bidding of a Shere Khan is in effect a piece of synchronicity, suggesting that examples could be multiplied endlessly. Then there’s the third but:

but one is compelled to look in shadows and be sorry for mottled bundles of bravado and ingrained hunger alternately huddling and howling.

Again, the poem turns away from particular actions: one is compelled (by what? a need to move from particular cases to an underlying phenomenon?) to pay attention to the Tabaquis, and in these lines the poem lands. Former Prime Minister John w Howard could evoke the myth of the Wild West and describe himself as the US’s deputy sheriff, and George W Bush could evoke the other US myth of the superhero and call Howard a man of steel. Maiden, leapfrogging on Putin, reaches further back to Kipling for a powerful alternative image of the relationship. The lines had me imagining Scott Morrison in camouflage gear, and sure enough I found a photo of him three years ago as almost literally ‘a mottled bundle of bravado’, here.

alternately huddling and howling. All children have been Tabaqui, lying for scraps from any father or mother,

These repeated lines now carry a little more weight, perhaps a suggestion of forgiveness, but really they are softening the reader up for the chilling final line:

and it isn't for the tiger the wolves come.

That gets me every time. Reading it in March 2022, on the 19th day of Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine it’s hard to get beyond that reference. In that context, apart from the putrid implication that Ukraine somehow provoked the attack, the line implies Putin and his wolves are pretty cowardly in attacking Ukraine rather than going after the real tiger enemy, the USA. But the poem has explicitly moved away from the Russia/Ukraine relationship, so the line is even more chillingly open-ended. Perhaps China will be a wolf for ‘famished Morrison’ and Australia with him. But the reference doesn’t need to be tied down. The poem is about a general syndrome, and the dangers it points to, at geopolitical or interpersonal levels, are real.

So the poem does indeed take us, as the lines I quoted near the start of this blog post suggest, to fear.

* Examples abound in Ox in Metal. Maiden reminds us that on the day of the celebrated misogyny speech Julia Gillard’s government reduced support for single mothers (‘Diary Poem: Uses of Iron Ladies’); she characterises the White Helmets in Syria as a false flag terrorist operation (‘Death-Wish Moths’); she reminds us that ‘Menzies made up the South Vietnamese invitation’ (‘There Seems an Easiness’); she describes the leaks of the Pandora, Panama and Paradise Papers as ‘a CIA self-amusing / parody of Wikileaks’ (‘Pandora and her Sisters’); she describes Joe Biden as ‘dreamy with dementia’ (‘The peace prize’); one of her characters notes that US drones and aircraft have killed many women and children in Afghanistan (‘Clare, George and Abdul Ghani Baradar’); another asserts that ‘most of the almost two hundred dead / at the airport in Kabul were shot / by naive young America soldiers’.