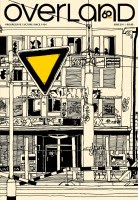

Jeff Sparrow (editor), Overland 214 Autumn 2014

There’s something irresistible about triplets: faith, hope and charity / birth, copulation and death / the three Graces / thesis, antithesis, synthesis / silence, exile, cunning … they’re everywhere. Overland‘s deputy editor Jacinda Woodhead invokes a nice one in this issue’s Editorial: for 60 years, she says, the journal has been encouraging dissent, interrogation and craft. It’s not just a pretty phrase: there’s plenty of all three in this issue, including in the first essay, Welcome to Curtin by Avan Judd Stallard, which comes craftily at Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers. It’s a memoir of working in the Curtin detention centre: prevented by the threat of seven years in prison from talking about the treatment of detainees, he describes instead the relationships and attitudes of the workers, with a short story writer’s eye for structure and significant detail.

Jennifer Mills, the fiction editor, introduces a 60th anniversary year feature, Fancy cuts, in which contemporary writers are invited to revisit short stories from the archives, invokes mother triplet: Overland has always been committed to the urgent, emerging or marginalised voices of its day. To kick off the feature, Josephine Rowe’s A small cleared space riffs surprisingly on Roma O’Brien’s When the bough breaks, a story of a hospital stillbirth that must have been harrowing when it was published in 1965, but now reads as a tale from an era of almost unbelievable callousness.

B J Thomason’s A slippery bastard deftly interrogates the myth of poet, horseman and Boer-murderer Breaker Morant, and in passing links him with two other mythologised slippery bastards. So we have triplet of Australian anti-heroes: Breaker Morant, Ned Kelly and Chopper Reed.

‘Cats are out, sloths are in’ by Jeff Sparrow is positively bursting with triplets. Subtitled Truth, politics and non-fiction, it looks at the fact-checking practice or otherwise of clickbait sites like Gawker, Buzzfeed, and Upworthy and more ‘serious’ liberal news sources like Crikey, the Conversation, the ABC. Current fact checking differs from the famous rigour of, say the New Yorker, in three significant ways (for which you’ll need to read the article). But checking facts has a limited usefulness, unless you realise they are part of a triplet: ‘facts’, theory and political practice.

There are three short stories in the Fiction section, including Anthony Panegyres’ Submerging, a parable about global warming embedded in a genuinely distressing tale of adolescent misery.

Up the back, are the three finalists in the 2013 Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize. Peter Minter, the judge, says he looks for poems in which every line ’embodies perception, ideation and the breath‘. That’s a lovely triplet. I’m sorry that I didn’t warm to any of the poems.

There are other triplets, including the three mysteries in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in The last space waltz? by Claire Corbett, but not everything comes in threes. Four columnists are entertaining and intelligent: Alison Croggon reflects on how literacy and orality affect memory and perception (a subject Ross Gibson tackles at length in his book about William Dawes’s notebooks, 26 Views of the Starburst World); Giovanni Tiso ponders gloomily on our changing concept of the future; Mel Campbell challenges habit of thinking of writing in terms of productivity; Stephen Wright managed to make me laugh a number of times in a column devoted to wishing he was funnier. I missed Rurijk Davidson, another regular columnist – on leave perhaps?

There are two excellent pieces that I couldn’t shoehorn into my numerical scheme. Brendan Keogh’s On video game criticism, cast as a letter to Susan Sontag, manages to communicate the intellectual excitement in its eponymous field, even to someone whose video game experience doesn’t go much beyond Space Invaders, Pacman and Tetris. Jill Jolliffe’s A new thalidomide? tells you more than you wish was true about hospital use of DES and other drugs, often without consent, on single mothers from the 1940s all through the 1960s in Australia, with health consequences still being discovered, including in the grandchildren of the women given the drug.

Sixty years of dissent, interrogation and craft! May the road rise to meet you, Overland, and the wind be at your back for at least 60 more.