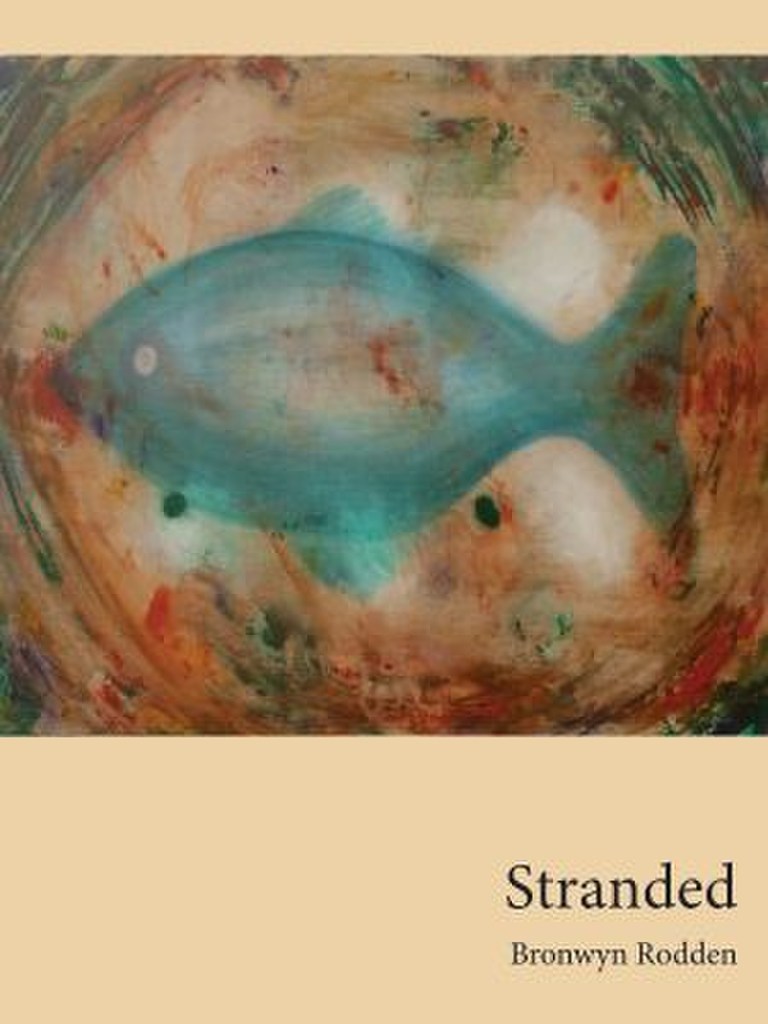

Bronwyn Rodden, Stranded (Flying Island Pocket Poets Series 2024)

I have brought a stack of books from the Flying Island Pocket Poets series on a winter holiday. They’re perfect travel companions – physically light and small in size, but with engrossing content.

In the title poem of Stranded, an animal

It sticks its fine-pointed

head into our picnic,

our anger doesn't move it,

its hunger ties it to us

It strikes me that Bronwyn’s poetry is a bit like that: the poems’ speaker sticks her fine-pointed head into all manner of subjects – places, people, animals, plants, paintings – with a hunger to observe and record. She travels to Ireland, Madagascar and Western Australia, stays in hotels in Adelaide and the Blue Mountains, and writes verse about what she sees.

Many of the poems are a very high-order version of the creative-writing exercise where you go for a walk around the block and then write a poem about what you have seen. It’s as if the reader is looking over the speaker’s shoulder on her travels and encounters. There’s an austere restraint about the poems: not the restraint of imagist poetry that aims to let the things speak for themselves, but a deliberate flatness of affect, an absence of reflexivity.

Because I’m short of time – so much walking and lying in the sun to do – I’ll limit myself to page 78. It’s a long way from being my favourite poem in the book, but a close-ish reading offers rewards:

Unusually, ‘Panda’ is a character sketch, but its unemotive language is characteristic.

Panda

Toenails round as fingernails,

vermillion ovals pretty as cellophane

bows tying up the beautiful,

lacquered package that was her.

The stanza begins with the word ‘toenails’ and only arrives at the person belonging to them, ‘her’, at the last word. I imagine the poem’s speaker sitting in an airport or a cafe when her attention is caught by the carefully-tended toenails of a woman sitting nearby. Her first observation is that they are ’round as fingernails’. I have never thought of fingernails as round, but I can tell that there’s something singular about these. Then, improbably, they are likened to cellophane, which is justified after the beautifully placed line break: like cellophane bows wrapping a parcel, they are the final touch to the woman’s beauty regime.

In this stanza, the speaker portrays the other woman pretty much as an extension of the beautifully tended toenails. She is objectified – the speaker sees her as having objectified herself, made herself into a ‘beautiful, lacquered package’. But there’s something unsettling about the speaker’s relationship to her: she’s just an observer, free to describe the other woman without engaging with her as another fully human person, unaware that she is doing the objectifying.

The point of view shifts in the second stanza.

It all went well till they moved

from Manila and the price of pedicures

zoomed from fifty cents to twenty-five

dollars. And she fell pregnant.

The woman is no longer an object but a person with a history. She has a nationality. She is in a relationship and has emigrated (‘they moved’). Her beauty regime has financial practicalities. She is a parent. The speaker is no longer summing her up on the basis of her toenails, but has engaged with her, imagining a life story for her. Or perhaps there’s a new speaker in this stanza, an omniscient narrator, or a friend who actually knows the woman and is tacitly reprimanding the speaker of the first stanza for her objectifying gaze. (Incidentally, notice the break at the end of the third line, which give the word ‘dollars’ a shocking emphasis.)

Then there’s another shift.

She’s still round as a panda,

and her toenails are in-grown

and her husband looks at her in

old photographs in bathing suits.

The first stanza may have been patronising, but it sketched a beautifully turned-out woman. Now it seems that her self-packaging is an attempt to keep the ageing process at bay. The pretty toenails of the first stanza are now in-grown. Perhaps time has passed. Or perhaps the speaker has taken a closer look and seen past the toenails’ prettiness to their painful condition. Their roundness has become a feature of the woman herself.

Why ‘still round’? Is roundness an attractive quality? If so, what’s going on with the husband? There’s a terrific line break: ‘and her husband looks at her in’ … Is it going to be pity, disgust, or even – as that ‘and’ allows to be possible – desire? She may still have the qualities her husband found attractive (‘She’s still round’), but it turns out he prefers images of her younger self.

The third stanza is elusive. The image of the woman as a panda sets her up to be a comic figure – round, cuddly, likeable, but not an equal to the observer. There’s pathos in the way she tries, and fails, to keep her youthful beauty. And something is not being said: we are left wondering what is happening for the speaker. Has she maintained her mildly satirical, racism-tinted distance? Has the poem tipped over into pity, even contempt? Or is there an unstated undercurrent of solidarity, fellow-feeling – one woman of a certain age to another?

On first reading, I would have gone with the second option – pity, even contempt. I was dismayed that my page 78 rule meant I had to write about this poem and might have to invoke ‘own voices‘ rhetoric. But as I’ve sat with it, let it unfold in my mind, noticed in particular the litany effect of the ands in the third stanza, I’ve come to read it as essentially comradely. The question, ‘I’ve called her ‘Panda’, what would she call me?’ lurks just benerath the surface.

To speak pedantically for a moment, there are no giant pandas on the Philippines.

I wrote this blog post on Wulgurukaba land, beautiful Yunbenun, where yesterday I saw an echidna going about its business in the late afternoon. I acknowledge the Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.