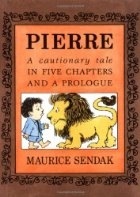

Maurice Sendak, Pierre (HarperCollins 1962)

I don’t generally blog about books I’ve re-read, but my blogging has been light-on recently as I’ve been reading mostly film scripts, which are exempt from my self-imposed task of writing about everything I read, so here’s a quick note on Maurice Sendak’s Pierre, which I re-read recently before wrapping it as a present.

I don’t generally blog about books I’ve re-read, but my blogging has been light-on recently as I’ve been reading mostly film scripts, which are exempt from my self-imposed task of writing about everything I read, so here’s a quick note on Maurice Sendak’s Pierre, which I re-read recently before wrapping it as a present.

Pierre: A cautionary tale in five chapters and a prologue was first published as a tiny book, cased with three others as The Nutshell Library. Our copies of those tiny books have long since disappeared after a huge amount of use and abuse. Besides Pierre, there are an alphabet book, Alligators All Around, a counting book, One Was Johnny, a book of the months, Chicken Soup with Rice. In case there’s anyone who doesn’t already know, Sendak was one of the 20th century’s greatest writers and illustrators for children, and though these books are in some ways very modest, absolutely obedient to the rules of their genres, each of them is a masterpiece. I have read them all aloud many many times to small co-readers and still love hem.

But Pierre has a special place. I think I first heard of it when my older brother took his eleven year old son on his knee and said,

Good morning, darling boy,

You are my only joy.

And when his son said, shockingly, ‘I don’t care,’ they both laughed.

And that’s the set-up: Pierre’s refrain is ‘I don’t care!’ Because it’s billed as a cautionary tale, the punitive saying ‘Don’t care was made to care’ can’t be far from an adult reader’s mind, as in the cautionary tales of Hilaire Belloc. For those who have so far been spared the delicious horrors of Belloc, let me mention ‘Jim, who ran away from his nurse and was eaten by a lion’. The title tells the whole story really – and then there’s this (punctuated as in the original):

His Mother, as She dried her eyes,

Said, ‘Well – it gives me no surprise,

He would not do as he was told!’

His Father, who was self-controlled,

Bade all the children round attend

To James’s miserable end,

And always keep a-hold of Nurse

For fear of finding something worse.

As a child I enjoyed Belloc’s tales of appalling retribution, confident that my own parents could never be that callous. And I enjoyed Roald Dahl’s even more gruesome variants when I read them to my children. But Sendak pushes the form beyond lip-smacking crime and punishment. Like Jim, Pierre is eaten by a lion as a direct consequence of his naughtiness. But whereas the father imagined by Catholic Belloc goes on to moralise, the Jewish Sendak’s parents, realising that their son is inside the lion, spring into action:

They rushed the lion into town.

The doctor shook him up and down

and when the lion gave a roar

Pierre fell out upon the floor.

He rubbed his eyes and scratched his head

and laughed because he wasn’t dead.

I may be idiotic, but that last couplet never fails to fill me with joy.

There’s a nice discussion of the whole Nutshell Library on the We Read It Like This blog, where there’s also an excellent reading.

tl;dr

tl;dr