David Adès, The Heart’s Lush Gardens (Flying Island Books 2024)

Apart from being a poet, David Adès is a podcaster. On Poets’ Corner, described on YouTube as ‘WestWords’ monthly encounter with celebrated Australian poets’, he has presented more than 50 poets, from Ali Cobby Eckermann to Mark Tredinnick. I could have linked to his conversation with Nathanael O’Reilly when I recently blogged about O’Reilly’s Separation Blues.

The Heart’s Lush Gardens, part of the Pocket Poets Series edited by Christopher (Kit) Kelen, is his fourth book. An introductory note dedicates it to the men in his men’s group, which has been meeting since 1992. ‘These Are the Men’, the title poem of the second of the book’s three sections, echoes that dedication:

Into their hearts' lush gardens

they took me,

gardens of unexpected flowerings

amid bracken and tangles of vines,

gardens where the soil had been laid bare

and seeds planted,

where I am welcome to roam and return.

That so resonates with the joy I remember feeling in my first consciousness-raising group (that’s what we called them in 1976).

This is not the only appearance of the men’s group, and masculine identity and the experience of being a man are broached in many other poems. ‘Slingshot’ imagines David facing Goliath without that weapon; ‘Small Man’ grapples with male entitlement (‘I am a small man in the house of my white skin, the skin of privilege’). The first poem in the book, ‘From Which I Must Always Wake’, is a complex, raw seven pages on heterosexual desire and relationship.

There’s a lot more. I’ll just mention ‘Ripples’, which a note tells us was inspired by a water-damaged original copy of someone’s thesis and poetry manuscript that Adès spotted abandoned on the footpath. The poem’s speaker addresses the writer of the lost work:

This is what you do not know:

who picks up the petal

you have dropped into the Grand Canyon,

who looks upon it in wonder

as if upon the first petal

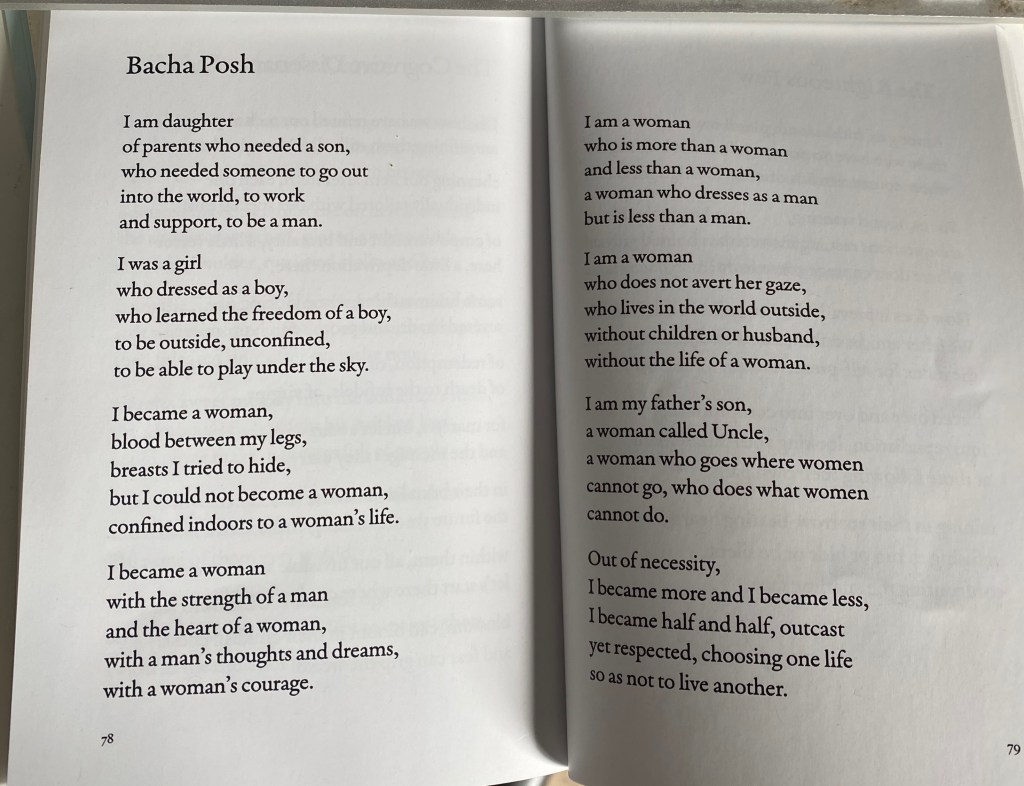

My arbitrary practice of looking at page 78* has borne fruit once again. The fine poem ‘Bacha Posh’, which starts on that page, has an interesting take on gender.

According to its Wikipedia entry, bacha posh is a practice in Afghanistan in which, often motivated by poverty, some families will pick a daughter to grow up as a boy. I probably didn’t need to look that up to understand the poem – but it’s good to know that it refers to an actual practice.

I don’t know David Adès, but I’m assuming he’s a cis man, and so likely to be regarded with suspicion if he enters the current public conversation about gender, and in particular trans issues. The practice of bacha posh gives him a way of letting his mind play over aspects of gender, and gender non-conformity, and invite readers to join him. Here, the non-conformity is imposed on the child rather than arising from an inner motivation such as gender incongruence.

This is a terrific example of a poem doing something that would be hard to do in a prose essay. It’s not arguing a case or offering an opinion. You could say it makes music from the language of gender. A handful of words and phrases repeat, almost like chiming bells. I don’t know how well this will work on the screen, but here is a nerdy look at how the gendered words and verbs of being and becoming occur in the poem.

I am daughter

of parents who needed a son,

who needed someone to go out

into the world, to work

and support, to be a man.

I was a girl who dressed as a boy,

who learned the freedom of a boy,

to be outside, unconfined,

to be able to play under the sky.

I became a woman,

blood between my legs,

breasts I tried to hide,

but I could not become a woman,

confined indoors to a woman's life.

I became a woman

with the strength of a man

and the heart of a woman,

with a man's thoughts and dreams,

with a woman's courage.

I am a woman

who is more than a woman

and less than a woman,

a woman who dresses as a man

but is less than a man.

I am a woman

who does not avert her gaze,

who lives in the world outside,

without children or husband,

without the life of a a woman.

I am my father's son,

a woman called Uncle,

a woman who goes where women cannot go,

who does what women cannot do.

Out of necessity,

I became more and I became less,

I became half and half, outcast

yet respected, choosing one life

so as not to live another.

I didn’t notice until I did that exercise that the final stanza no longer has any gendered words, an eloquent absence. In addition, it repeats the phrase ‘I became’, the phrase of transition, three times. And, in contrast to the first stanza where the poem’s speaker has no agency (‘I am daughter / of parents who needed a son’), here he/she is engaged in a dynamic continuous act of choosing.

Having done that little erasure experiment, I now see that there are other bells in this chime. Active verbs are scattered throughout, appearing more densely towards the end (‘goes’, ‘go’, does’, ‘do’, ‘live’); and the prepositions ‘with’ and ‘without’ have a sort of call and response between stanzas 4 and 6.

Apologies for the nerdiness of this, but if you’ve got this far I hope you’ve enjoyed looking with me. I hope it, and the poem, make a small contribution to Trans Awareness Week, 13–19 November.

I have written this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora nation. I acknowledge Elders past and present of those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.