Ed Brubaker, Night Fever (art by Sean Phillips, colors by Jacob Phillips, Image 2023)

I’m steadily making my way through the pile of books I was given as Christmas presents. As always the pile includes some excellent comics. We Are Not Strangers is one (blog post here). Night Fever, which could hardly be more different, is another.

Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips are a prolific team of comics makers. I’ve read their work in a number of genres – Hollywood noir, fantasy spy stories, and horror, though none of them is necessarily constrained to just one genre. Unlike most of their comics, Night Fever is a stand-alone story rather than part of a series. It shares the physical and moral darkness of their other work.

The narrator-protagonist, Jonathan Webb, is a sales rep for a US publishing company who once dreamed of being a writer. In Europe for a book fair, filled with a sense of failure, he crashes a decadent upper-class party, an orgy like the one in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, by pretending to be someone whose name he spotted on the guest list.

As every genre reader knows, it’s dangerous to borrow someone else’s identity, especially if they have access to a boundary-pushing party attended by the super rich. Sure enough, Jonathan is caught up in all manner of terrible things: alcohol, drugs and debauchery as you’d expect, but then there’s larceny, murder and an exploding police car. As one caption puts it, ‘Crime is the biggest high in the world.’

But crime doesn’t pay. Or does it? Will he ever find his way back to mundane life, his loving wife and their two sons? And if he does, will he be content? Or will he be haunted by this week when he threw off the shackles of decency? And who is the stranger Rainer who leads him deeper and deeper into the darkness?

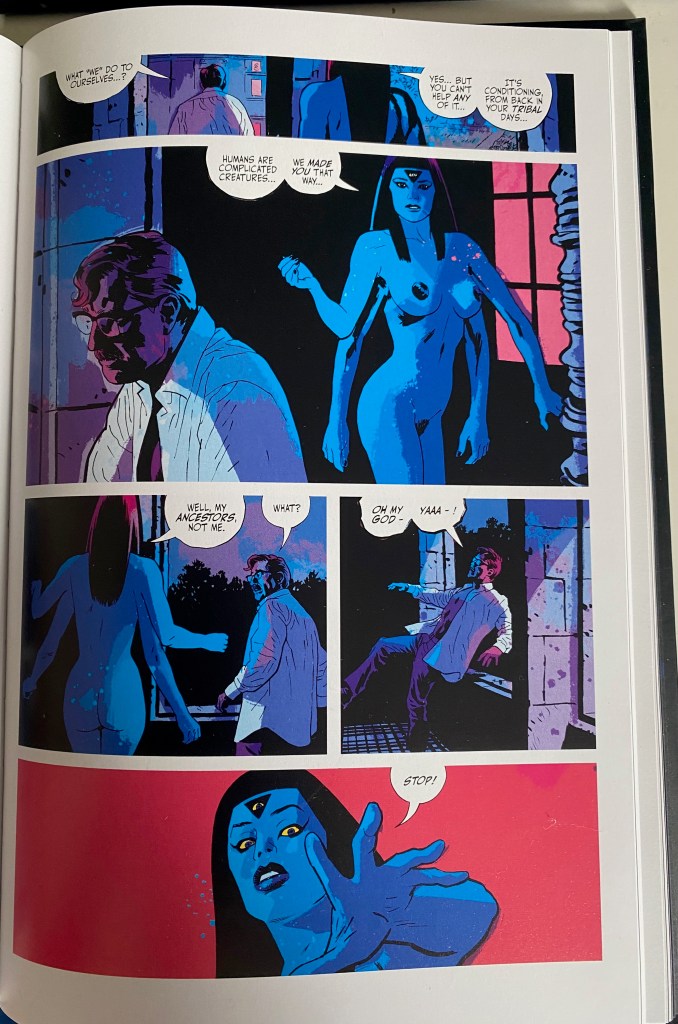

Page 77* give you a taste of the art work, including the dark palette. It’s also an example of the genre-blending quality of Brubaker and Phillips’s work. Jonathan has visited a bar where he’s been warned, too late, not to drink anything because, ‘They put a lot of stuff in the cocktails here.’ There follow a number of pages where black space represents things he doesn’t remember of the night, and the rest is full of jumbled images of debauchery and violence. This page is a moment of calm, in which the owner of a voice that has been speaking to him from the shadows is revealed:

Ah, you might think, this is where the story gets really weird. The next thing Jonathan remembers is being back at a party. Maybe she saved him, maybe he landed on something soft, maybe it was a drugged hallucination. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that at this stage, Dave Brubaker himself wasn’t sure which way the story was heading. Another blue, four-armed person turns up a couple of pages later, and someone tells Jonathan that the aliens ‘have been coming more often lately … getting ready for the end’.

This page is also a good example of the objectifying treatment of women’s bodies that is my main dislike of comics like this. Thankfully this is the only naked woman in the book. I guess if you have scruples about pervy comic-book misogyny, you can always slip in a naked woman by giving her a second pair of arms and making her a godlike alien. (A full-frontal naked man turns up later, but he’s dead and not the least bit sexy.)

To quote my gift-giving son about another Brubaker-Phillips book, ‘It’s popcorn.’ It’s quality popcorn.

The first horror story I ever heard was told me by a Bundjalung woman – and it was much scarier than anything in Night Fever. I wrote this blog post on land of the Gadigal and Wangal people. I acknowledge their Elders past and present who have told stories here and cared for this land for millennia.

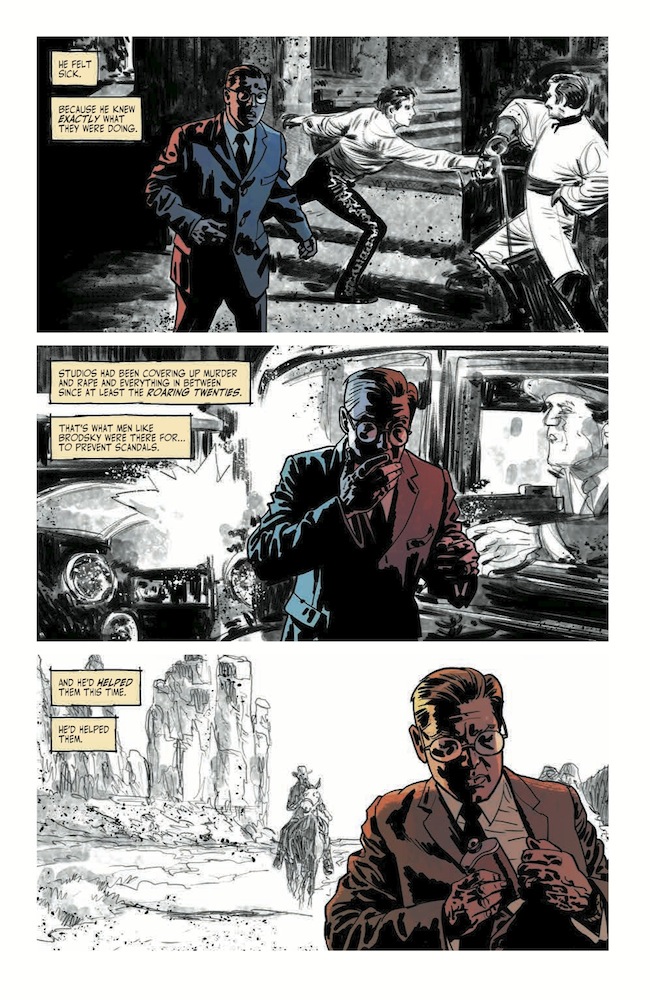

There’s a lot of old Hollywood anti-Communism around just now. On Thursday night I saw Jay Roach’s Trumbo at the movies. On Friday night we had a family birthday outing to the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! On Saturday I read this birthday-present comic, the final ‘Act’ ofFade Out. All three deal with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s attack on Hollywood writers in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

There’s a lot of old Hollywood anti-Communism around just now. On Thursday night I saw Jay Roach’s Trumbo at the movies. On Friday night we had a family birthday outing to the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! On Saturday I read this birthday-present comic, the final ‘Act’ ofFade Out. All three deal with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s attack on Hollywood writers in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

A beautiful woman is murdered in the first couple of pages, and the crime scene is altered to make it look like suicide. Charlie sets out to investigate and uncovers as much corruption, secretiveness and deranged viciousness as Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade could ever have wished for. He also gets beaten up quite a bit and gets involved with the beautiful woman who has replaced the murder victim in the film they’re all makng. He and Gil have a difficult relationship, not helped by Gil’s alcohol intake and his tendency to want to speak truth to power without regard for the consequences. Some real characters appear: Clark Gable knows Charlie from his war days, and Dashiell (‘Sam’) Hammett gives advice on how to flush out a murderer.

A beautiful woman is murdered in the first couple of pages, and the crime scene is altered to make it look like suicide. Charlie sets out to investigate and uncovers as much corruption, secretiveness and deranged viciousness as Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade could ever have wished for. He also gets beaten up quite a bit and gets involved with the beautiful woman who has replaced the murder victim in the film they’re all makng. He and Gil have a difficult relationship, not helped by Gil’s alcohol intake and his tendency to want to speak truth to power without regard for the consequences. Some real characters appear: Clark Gable knows Charlie from his war days, and Dashiell (‘Sam’) Hammett gives advice on how to flush out a murderer.