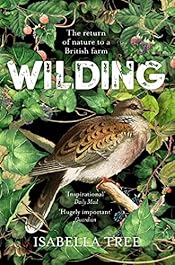

Isabella Tree, Wilding: The return of nature to a British farm (Picador 2018)

The environmental-activist friend who gave me this book for Christmas says he gives it to everyone. Having read it, I can see why. Apart from its fascinating subject matter, it’s very engagingly written. My friend wrote on the title page, ‘A taste of what the future holds (if there is one)’.

Isabella Tree (her real name) and her husband Charlie (Sir Charles Burrell) were dairy farmers in Sussex. They were also the lord and lady of Knepp Castle, Charlie’s ancestral home. In the 1990s, in spite of following all the best practice recommendations of the time, their dairies were operating at an unredeemable loss, so they decided to put their 3,500 acres (1,400 hectares) to different use. First they sought and received funding to make part of the land into a park, and eventually the whole property became what is now the Knepp Wildland rewilding project.

The book ia an exhilarating account of the process of bringing that change about – or to a great extent allowing it to happen, as a lot of what was needed, it turned out, was for well-meaning humans to get out of the way of natural regeneration. I won’t try to summarise the process. Enough to say that the experience of Knepp has challenged many received ideas about what the English countryside was like before large-scale human intervention. It seems unlikely, for example, that the country was covered in closed-canopy forest – grazing and browsing animals would have kept a lot of the land relatively open, and the much treaured English oaks don’t grow well in a closed-canopy environment.

That orthodoxy isn’t the only one to be challenged. Isabella Tree writes persuasively about the phenomenon of the shifting baseline: people think back with nostalgia to the land as they knew it in their childhoods, thinking of that as its natural state – whereas in fact that state was already deeply affecred by industrialisation. Animals and birds who are regarded by the scientific community as belonging to a particular habitat turn out, once destructive processes have been reversed, to prefer quite a different one – the one we have seen them in all our lives is just the best they could manage given that their preferred homes had been destroyed.

Film critic Mark Kermode is fond of saying that a good documentary can make you interested in a subject you didn’t think you cared about. That’s true of this book. It’s not that I don’t care about environmental issues, but I thought I knew enough about rewilding when I knew that wolves had been restored to Yosemite in the USA with extraordinarily beneficial effects. This book discusses that and laments the unlikelihood of wolves being allowed onto the Sussex estate, but it also makes me care about nightingales, turtle doves, butterflies (there’s a brilliant description of butterflies kelling), oaks and water violets.

Isabella Tree even makes compelling reading from the business of forming committees, consulting experts (including a brilliant forerunner of Knepp in the Netherlands), dealing with grumpy neighbours and dealing with government bureaucracies.

Because one of my regular readers loves them, I can’t resist quoting this lovely passage about pigs from Chapter 6, in which old English longhorns, Exmoor ponies and Tamworth pigs (approximations of the animals that were on the land before human activities wiped them out) are introduced to the estate (page 109-110):

Intelligent, inquisitive, imperious, myopic, sociable, gluttonous, grunting, ungainly, it is easy to recognize ourselves in them … Which is why, perhaps, the Tamworths are constantly forgiven their antics at Knepp. The instant they were let out of the acclimatisation area in the Rookery, they applied themselves to destroying Charlie’s manicured verges along the drives with the unstoppable momentum of forklift trucks. Then, two abreast, they unzipped the turf down the public footpaths, following the exact routes on the Ordnance Survey map, heading diagonally across the fields. We realised that what they were doing, with the undeviating propulsion of slow-motion torpedoes, was zeroing in on slivers of the park that had never been ploughed – margins rich in invertebrates, rhizomes and flora. In the first few days of their release the pigs drew an accurate blueprint of what modern farming had done to our soil.

The ornamental grass circle in front of the house, another patch of pristine turf, proved to have a magnetic attraction, too, and Charlie was compelled to take to his bicycle, jackeroo stock-whip in hand, to impress upon them that this area was sacred ground …

As Winston Churchill once observed, ‘A cat looks down on you. A dog looks up to you. A pig looks you straight in the eye.’

As a relatively ill-informed Australian, I read the book with a double mind: on the one hand learning so much about what remediation looks like in England, and on the other wondering what would have to be done to reverse the relatively more recent but possibly more radical damage done to Australian environments by, for example, hard-hoofed grazing animals, artificial fertilizers, and crops like sugar cane or wheat. Bruce Pascoe and Lyn Pascoe’s work at Yumburra might be a partial answer. I’d love to see them in conversation with Tree and Burrell.