Jock Serong, The Rules of Backyard Cricket (Text 2017)

I was given The Rules of Backyard Cricket as a gift some years ago. Friends had told me it was excellent, but I knew nothing about it. The cover illustration, which shows two small boys in silhouette, one of them pretending to shoot the other in the back of the head, suggested that it might be less benign than the ‘Cricket’ episode of Bluey.

The opening chapters have a lot in common with that episode. Two brothers in the suburbs spend endless hours playing cricket with makeshift equipment and their own idiosyncratic rules. Like Bluey‘s Rusty they become excellent and go on to bat for Australia.

But that’s where the similarity ends: the brothers, Darren and Wally Keefe, are locked in vicious mutual combat even while their brotherly bond is strong, which puts the book in a long tradition of stories about quarrelling brothers: think Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau, Romulus and Remus, William and Harry. As they come to prominence in the cricketing world, Darren, the younger brother, attracts headlines for his off-pitch misbehaviour with drugs and chaotic relationships, and a terrible hand injury excludes him from cricketing heights. Wally becomes captain of the Australian team and can be depended on to present the ideal face of professional sport, though his personal life suffers under the strain. They typecast themselves: ‘Wally as responsible, grave: a leader. [Darren] a force of nature: a talented freak with no mooring.’ (Page 73)

In the background is the world of organised crime, match-fixing and corruption – embodied in Craig, their friend from teenage years who now lives a shadowy criminal life. Also in the background is their single mother, whose unfailing belief in both of them has been crucial to their success, and their long-suffering women partners, where I choose the word ‘suffering’ deliberately.

At the start of the novel, Darren is locked in the boot of a car, on the way to an unknown destination where, he assumes, he is about to be killed. He’s not sure who is going to kill him or why, and as he tries to work his way free he thinks back over his life, and in so doing narrates the book. Each chapter begins with a brief report on what’s happening in that boot, a device that both reassures readers that the story is something other than a biography of two fictional sportsmen, and challenges us to spot the moment when Darren falls foul of someone murderous.

I’m not a cricket fan, but I can follow a conversation about it (unlike the AFL in Helen Garner’s The Season). I loved the descriptions of cricket matches here – the fast bowling, the sledging, the many technicalities. Some readers will need to skim those bits. I’m with them in not getting most of the references to famous cricketers, but it didn’t worry me.

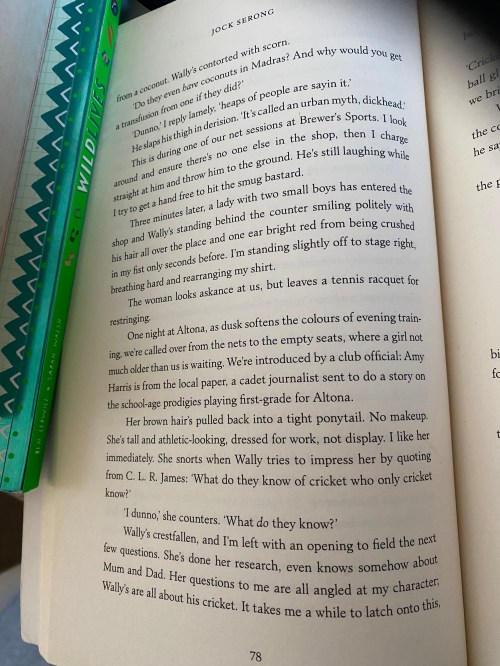

On page 78*, about a quarter into the book, the teenaged brothers have recently moved out of home. Wally is being recognised as a cricketer of ‘phenomenal self discipline’ but, according to Darren, when they play in the back yard he’s still ‘vengeful, savage and petulant’. They are in a sports-gear shop where Wally has a job, and where Darren visits to play with the cricket gear.

Two things happen on this page, one to do with the boys’ relationship and the other introducing a character who will play a crucial role. First, Wally sneers at Darren for believing an improbable story about a Test cricketer being given a transfusion ‘from a coconut’:

I look around and ensure there’s no one else in the shop, then I charge straight at him and throw him to the ground. He’s still laughing while I try to get a hand free to hit the smug bastard.

Three minutes later, a lady with two small boys has entered the shop and Wally’s standing behind the counter smiling politely with his hair all over the place and one ear bright red from being crushed in my fist only seconds before. I’m standing slightly off to stage right, breathing hard and rearranging my shirt.

The woman looks askance at us, but leaves a tennis racquet for restringing.

There’s comedy in the way the brothers fight compulsively like much younger children. But there’s something unnerving about the way Wally laughs and recovers quickly to present a polite face to the world. By referencing stage directions – ‘slightly off to stage right’ – Darren invites us to visualise the scene: one brother stands centre stage as far as the world is concerned, while the other is a dishevelled and disreputable support actor. This is the story as seen by the latter, and the scene is emblematic of their relationship.

Then:

One night at Altona, as dusk softens the colours of evening training, were called over from the nets to the empty seats, where a girl not much older than us is waiting. We’re introduced by a club official: Amy Harris is from the local paper, a cadet journalist sent to do a story on the school-age prodigies playing first-grade for Altona.

Her brown hair’s pulled back into a tight ponytail. No makeup.

She’s tall and athletic-looking, dressed for work, not display. I like her immediately. She snorts when Wally tries to impress her by quoting from C. L. R. James: ‘What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?’

‘I dunno,’ she counters. ‘What do they know?’

Wally’s crestfallen, and I’m left with an opening to field the next few questions. She’s done her research, even knows somehow about Mum and Dad. Her questions to me are all angled at my character; Wally’s are all about his cricket. It takes me a while to latch onto this, but like an idiot I play extravagantly into her hands.

Darren’s extravagance gives Amy her headline when he says that he and Wally bring people what they want from cricket now, drama and action: ‘Bradman is dead.’ It’s one of Darren’s rare victories in their lifelong rivalry – and like all his victories it’s a bit on the nose.

If you don’t know who Bradman was, you’d be pretty lost in this book. But you don’t necessarily have to know about C. L. R. James. In fact, it feels as if Jock Serong is speaking directly here, as it seems unlikely that Darren would have read the work of Trinidadian Marxist intellectual C. L. R. James, even if he had heard James’s riff on Kipling’s, ‘What do they know of England who only England know?’ Whether Amy knows where the quote comes from doesn’t matter. She sees it for what it is, a bit of misjudged pretension on Wally’s part. She’s out for a juicy headline. She’ll continue to be out for juicy stories for the rest of the book.

Like the fighting between the brothers, the headlines get darker as time goes by. So yes, the book is about cricket – backyard, community, state, international test and one-day varieties. It’s also about the corrupting effects of capitalism on sport, about masculinity toxic and otherwise, about the damaging effects of celebrity, about the role of the media. And it moves at a ripping pace.

I wrote the blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation where the days may be be growing warmer and lorikeets are starting to make their presence known. I acknowledge Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.