This blog couldn’t possibly keep up with my grandchildren’s reading. The other day, the six-year-old pleaded to go to the library, and in the very small time we had there she chose a book about a girl called Paris who visits Paris. A little later a friend saw this book and offered to lend us her Madeline compendium. After I’d calmed down from reciting the first 10 pages or so of Madeline (which the Emerging Artist claims never to have heard of, so who knows how, when and where I got to know most of it off by heart), we accepted her offer.

Meanwhile, the grandies’ father brought home a new book by Jon Klassen, a writer and ilustrator of a very different kind.

Ludwig Bemelmans, Mad about Madeline: The complete tales (Viking 1993)

This huge volume includes all six Madeline books, in order of appearance here:

- Madeline (© 1939)

- Madeline and the Bad Hat (©1956)

- Madeline’s Rescue (©1951, 1953)

- Madeline and the Gypsies (©1958, 1959)

- Madeline in London (©1961)

- Madeline’s Christmas (©1956)

We read the first story to the three-year-old. The six-year-old was interested in other things, but her ears pricked up in the course of the reading – it may have been the insistent rhymes, or the sense of danger (‘To the tiger in the zoo / Madeline just said pooh-pooh’), but she joined us and then asked for that story to be read two, or maybe three, more times right then. She listened with intense concentration. Her little brother was interested in why Madeline said ‘pooh-pooh’, but her focus was a lot less scrutable.

In case you don’t know, Madeline is the youngest and boldest of 12 little girls (‘in two straight lines’) who lead a regimented life in an old house in Paris all covered in vines. In just a few lines of verse per beautifully illustrated page the story unfolds of her having her appendix out. When the other girls see the treats she receives in hospital, and the scar, they want to have theirs out too. The illustrations, meanwhile, amount to a guided tour of Paris’s famous sites. (The three year old didn’t care about Montmartre or the Eiffel Tower, but he loved the ambulance every time.)

That’s the first book. Of the others, I most enjoyed Madeline’s Rescue, where Madeline falls into the Seine. In the first book, the text ‘Nobody knew so well / How to frighten Miss Clavell’ accompanies an image of Madeline balancing precariously on a wall above the river. That’s repeated in Madeline’s Rescue, but the facing page image shows her falling, with the text, ‘Until the day she slipped and fell.’ She is saved by a dog, who then goes home with the little girls. There’s a riot in the dormitory over who the dog will sleep with. In the end, the dog, whose name is Genevieve, has twelve puppies and everyone is happy.

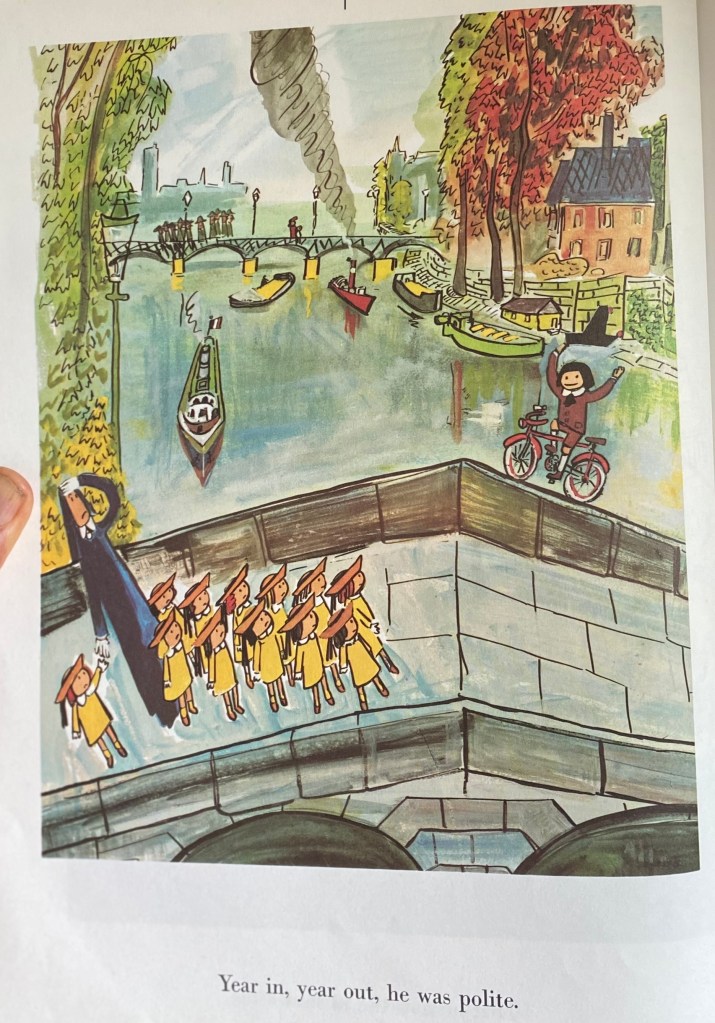

Page 76 falls in my least favourite of the books, Madeline and the Bad Hat, in which Pepito, who lives next door to the girls, behaves abominably. He is cured of his wicked ways in the end, but we didn’t get there in our group reading, as the six-year-old didn’t see why she should persist with the tale of misbehaviour – and the three-year-old had his own reasons for not being interested in someone else’s bad choices (a phrase heard too often at his childcare centre). But page 76 is a lovely example of Ludwig Betelmans’ artwork (click to enlarge), and the way it plays with the text:

Pepito is riding dangerously on the edge of the bridge, causing Miss Clavell to clutch her brow (she does a lot of that, and she is often seen slightly off balance as she is here, holding Madeline’s hand) and alarming the little girls. However, as the text points out, he is raising his hat politely. Most of his bad behaviour, in fact, is seen in the images but either ignored or downplayed in the text – so we know he is sneakily bad, and mostly avoids adult retribution. On the next page, for example, the text reads, ‘He was sure and quick on ice,’ and we see him running rings around all the little girls at a skating rink, knocking them off balance. I begin to understand my granddaughter’s concentrated attention.

That’s all happening in the foreground. The background (gouache, I think) is where the charm of these books lies: the bridge itself, of course, is beautiful, then there is the other bridge across the Seine, the boats and the trees with their autumn colours.

This is one from the past that has survived the passage of time brilliantly.

Jon Klassen, The Skull: A Tyrolean Folktale (Walker Books 2023)

John Klassen is a favourite in our family. See, if you like, my blog posts on I want My Hat Back (2011), This Is Not My Hat (2012) and We Found a Hat (2016).

This book is less minimalist than those earlier ones, but just as grimly comic. In the folktale that it’s based on, a little girl befriends a skull, and a headless skeleton demands that she hand it over. In Klassen’s version the girl, whose name is Otilla, refuses to surrender the skull, manages to outwit the skeleton and dispose of it in a gruesome way that ensures it will never return. She and the skull, it is implied, live happily ever after.

I wasn’t at alI sure how suitable this story was for my squeamish granddaughter and vulnerable grandson. I read it with them once, and moved on as quickly as I could. I can only assume that their father and/or mother read it to them a number of times before we next saw each other, because they both started chanting, ‘Give me my skull. I want my skull,’ and then roared with laughter when, on the fourth or fifth repetition, they fell silent after ‘my’. In the book, that’s the moment when the skeleton falls off the castle wall and is broken up. I guess Jon Klassen is a better judge than I am of what children will enjoy.

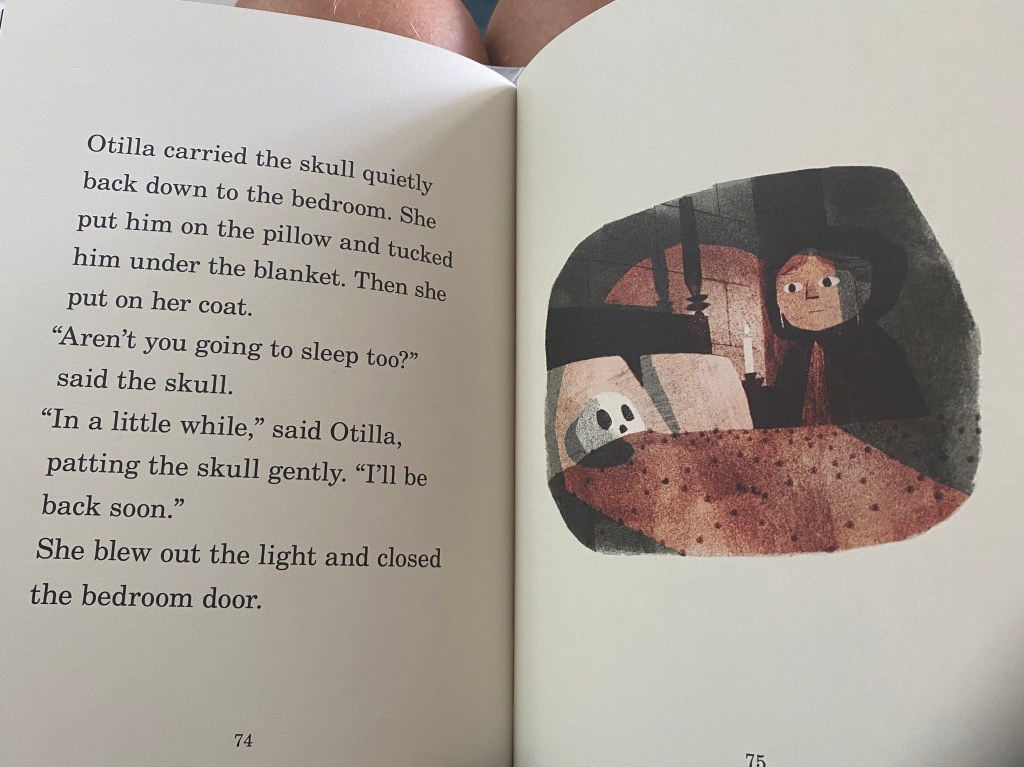

Page 76 is blank, before the start of a new chapter, so here’s the preceding spread, to give you an idea of the storytelling:

This is just after the terrifying encounter with the skeleton that ends with it falling off the wall. Otilla is about to gather up its bones, smash them, burn them and throw them into a bottomless pit. But first there is this still, intimate moment. The tenderness of the text – Otilla carries the skull quietly and pats it gently – is beautifully realised in the warmth of the candlelight, the way the blanket covers the skull’s mouth, Otilla’s calm expression.

These books are unlikely blogfellows, but there’s an unexpected echo of Madeline on this page from The Skull. Aficinados will recall the final moment of the first Madeline book:

And she turned out the light –

and closed the door –

and that's all there is –

there isn't any more.