Lizz Murphy, Bitumen Psalms (Flying Island 2024)

This book is another jewel in the Flying Island Pocket Poets series, more than 100 pocket-sized books (14 x 11 cm) so far, published under the stewardship of Kit Kelen. It’s a wonderful series, in which well-established poets appear cheek by jowl with brand new talents. You can subscribe here to receive 10 books at the start of each year.

The poems in Bitumen Psalms are mostly short, or sequences of short stanzas that might be stand-alone poems. I had to consult the table of contents a number of times to check whether what I was seeing on a page was a number of separate poems or the stanzas of a single poem. Mostly they weren’t, but publishing the poems without titles leaves open the possibility of reading them all as one continuous mega-poem.

The book is in seven sections. The first, ‘Bitumen Psalms’, is a long poem made up of short stanzas, each a glimpse seen from a car travelling from inland New South Wales to the sea. A recurring line, ‘I forbid the camera’ spells it out: these are word snapshots – similes and haiku-like compression in place of shutter-clicks.

‘All Weathers’ is seven pages of glimpses of people. ‘Marking Time’ is spent in hospital, whether as visitor or as patient is not clear, and doesn’t need to be. ‘Cast Your Wing’, the section I enjoyed most, begins with the poem ‘I don’t go outside often enough’, and takes the reader out into a world of birds, animals, clouds and light. ‘Things’ takes us back inside again, mostly, for three pages of, mostly, domestic objects wittily observed. ‘Shudders’ is three pages of computer-related joke-poems. ‘Breath and Air’, the final section, has four longer poems in which birds feature. It includes the killer lines (in ‘Under the filling moon’):

A hundred thousand

children at risk

and I am writing about birds

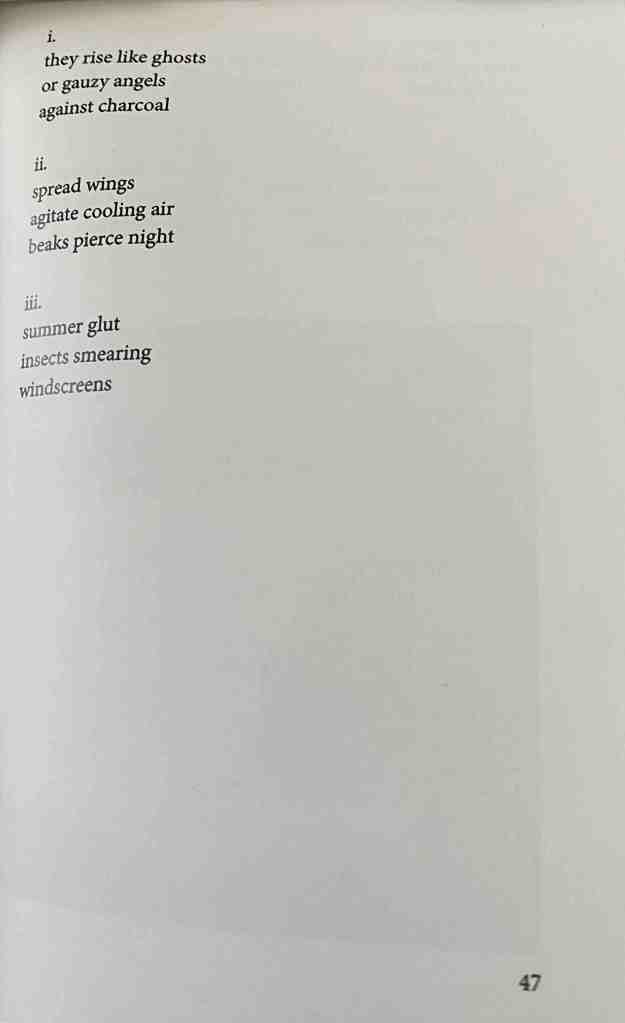

Like most of those in the book, the one on page 47* is untitled. It differs by giving clear indications that the three blocks of print are to be read as a single poem in three parts.

Exactly how they constitute a single poem isn’t straightforward.

On first reading section i, I expected to following sections to clarify who they are who ‘rise like ghosts’ – birds, perhaps, or moths? And section ii seemed to be heading that way with its wings and beaks – ah, it’s birds. But section iii puts the kibosh on that, being definitely about insects.

My initial expectation having been thwarted, I take a pleasurable moment to sit with the poem, to simply enjoy its three images and let any connections arise. I have to suppress the impulse to figure out, even nail down, what the poet had in mind, but I’m gradually learning what critics of contemporary poetry mean when they say that it’s the reader’s job to create meaning in a poem as much as it is the poet’s. (Or sometimes, they say, the job of a number of readers collaborating: so feel free to say something in the comments section.)

i.

they rise like ghosts

or gauzy angels

against charcoal

This vividly evokes white and fluttering things taking to the air at night. (I get the whiteness from ‘like ghosts’, and the fluttering from the sound of ‘ghosts / or gauzy’, and of course they have the wings of angels.) It doesn’t identify them. While that creates a kind of puzzle for the reader, it’s not the main effect. It’s more like an invitation to reflect on the image, to bring your own experience to bear on it, or to let it do the work, calling up images from your mind. It gives the reader room to reflect.

I saw moths, but then:

ii.

spread wings

agitate cooling air

beaks pierce night

The strong sound of ‘spread wings’ contrasts with the flutteriness of the first section, and the night-piercing beaks make it clear that these are not the same creatures. Perhaps the poem is simply turning its attention to a new subject, a new image, something else the poet sees as night falls. But there’s something purposeful about these birds, their wings and beaks. I catch a hint that they are swooping to prey on the moths, swallows perhaps, and now I can’t read the lines any other way.

The third section, at first a jarring contrast to the observations of nature that precede it, now fits.

iii.

summer glut

insects smearing

windscreens

The subject is still the death of insects, but the language of economics (‘glut’) and technology (‘windscreens’) intrudes. It’s a very different death from the targeted killing by hungry birds – it’s now happening on an industrial scale, and it’s soulless, collateral damage. And is it just me, or is there an edge of nostalgia here? Having insects smeared on a windscreens used to be a feature of long-distance drives in the country. In my experience this is no longer so. The summer glut is a thing of the past. This is not just death of individual insects, but the wiping out of populations. The poem has moved from a gentle observation of insect and bird life to a deep sorrow about the state of the world. Or at least it has moved me in that way.

I love this book. You can flip it open at any page and find something to smile at or mull on.

I wrote this blog post on unceded Wulgurukaba land, Yunbenun, where yesterday I met a family of five red-tailed black cockatoos, gorgeous and unafraid. I acknowledge Elders past and present who have cared for this country for millennia, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78. The last poem in Bitumen Psalms finishes on page 75, so my personal algorithm sends me to page 47 (I was born in 1947).