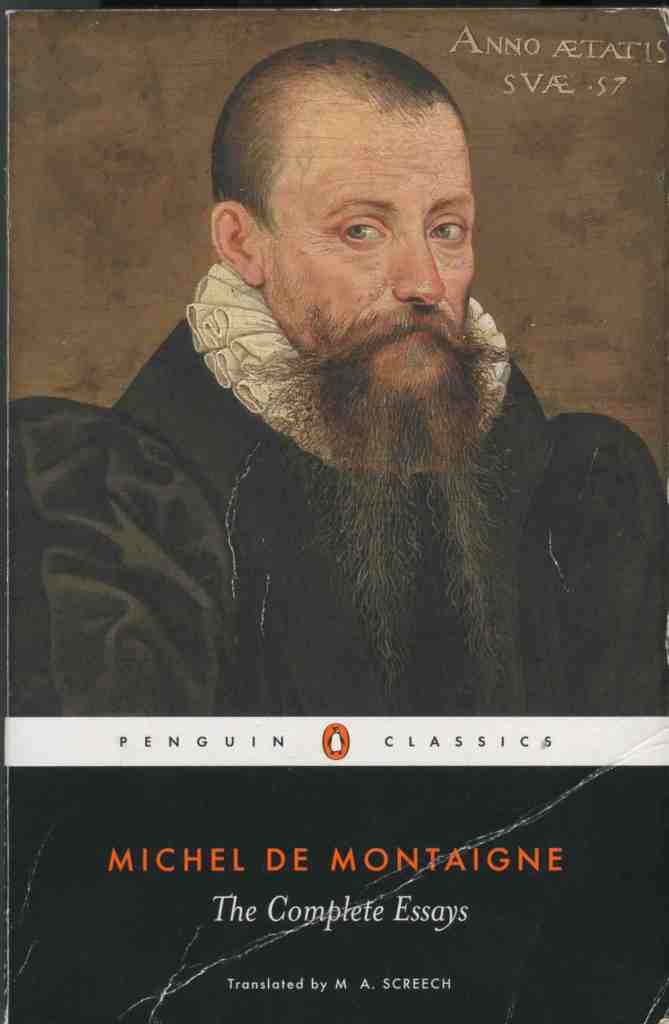

Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays (Penguin Classics 1991, translated by M. A. Screech)

– end of Book 2 Essay 12, “An apology for Raymond Sebond’ to part way through Book 2, essay 17, ‘On presumption’

The month has flown by, and it’s time for another progress report on my project of reading Montaigne’s essays, four pages every morning. Two friends have sent me examples of Montaigne cropping up in their own reading: the first has just started reading Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow, and was reminded of my project when the confined Count finally gets to read Montaigne; the second forwarded me Nicholas Gruen’s weekly newsletter for the 18th of August, which includes Montaigne’s essay ‘On a Monstrous Child’. I’m not alone in reading him.

It’s taken much more than a month, but I’ve now finished ‘An Apology for Raymond Sebond’. Whether from shrinking attention span, lack of interest, or the nature of the essay itself, I happily confess that I had trouble following its argument. It went on and on, endlessly quoting ancient philosophers, repeating itself, and proclaiming radical scepticism. I thought it was about to discover the scientific method, but no, it seemed to end up saying you can’t trust reason or the senses, but – implied rather than stated outright – you can always trust the revealed Word of God. I’m glad that one is behind me.

Today I’m part way through ‘On Presumption’. Having discussed in the preceding essay the relative worthlessness of reputation (‘glory’) compared with actual virtue, in this one Montaigne begins by saying that one’s opinion of oneself is similar to glory – prone to wishful thinking and no real indicator of one’s real worth. He’s now in the middle of a generally unflattering – and I think intentionally funny – self-portrait. He loves poetry, but is a terrible poet. He loves fine writing but:

There is nothing fluent or polished about my language; it is rough and disdainful, with rhetorical arrangements which are free and undisciplined. And I like it that way, by inclination if not by judgement. But I fully realise that I sometimes let myself go too far in that direction, striving to avoid artificiality and affectation only to fall into them at the other extreme. … Even if I were to try to follow that other smooth-flowing well-ordered style I could never get there. (Page 725–726)

False modesty? Maybe not. It does read as a genuine attempt to describe his own writing.

Beauty, he says, is the ‘first sign of distinction among men’, and height is the only quality that determines manly beauty, but his own ‘build is a little below average’. In one of the passages that makes reading him such a pleasure, he lists the qualities that don’t count:

When a man is merely short, neither the breadth and smoothness of a forehead nor the soft white of an eye nor a medium nose nor the smallness of an ear or mouth nor the regularity or whiteness of teeth nor the smooth thickness of a beard, brown as the husk of a chestnut, nor curly hair nor the correct contour of a head nor freshness of hue nor a pleasing face nor a body without smell nor limbs justly proportioned can make him beautiful. (Page 729)

Having just told us that only height matters, he implies the counter argument: he’s at least a bit sorry that men who look good and don’t smell bad aren’t regarded as beautiful. Not that he attributes those qualities to himself. He says his build is ‘tough and thickset’ and describes (in Latin, possibly quoting someone) his bristly legs and tufty chest, etc.

So this isn’t so much a progress report as a snapshot of where I’m up to when the blog post falls due. I just flicked forward 120 pages to see that next time I may be talking about an essay entitled ‘On three good wives’!

This blog post was written on Gadigal-Wangal land, where understandings of the universe beyond Montaigne’s imaginings were developed millennia before the Ancients he discusses. The weather is warming up alarmingly early. I acknowledge the Elders past, present and emerging of the Gadigal and Wangal Nations,.