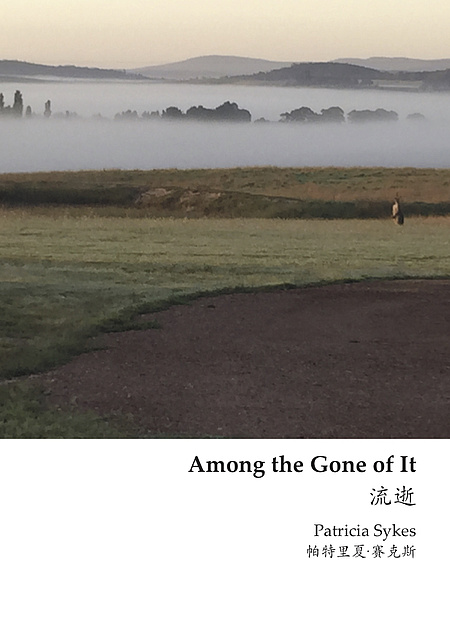

Patricia Sykes, Among the Gone of It, with Chinese translation by Xu Daozhi and Wu Xi (Flying Island Books 2017)

This is my fifth post for National Poetry Month, and my third bilingual book this month from the Flying Island Poets series.

A web search for “Patricia Sykes poet” produces a large number of hits that begin, ‘Patricia Sykes is a poet and librettist.’ She has collaborated with composer Liza Lim to create The Navigator, a chamber opera, and a number of her poems have been set to music. As a child she was a resident in the Abbotsford Convent orphanage in Melbourne (now an arts precinct), and as an adult she was a member of the Women’s Circus, both of which have been subjects of her poetry – in The Abbotsford Mysteries (2011) and Wire Dancing (1999) respectively, both published by Spinifex Press.

Of the translators, Xu Daozhi has a PhD in English literature studies from the University of Hong Kong and Wu Xi is a poet and scholar who was also stationed in Hong Kong at the time of translation. Again, I can’t comment on their work except to admire its visual beauty.

The poems in Among the Gone of It that spoke to me most strongly were those dealing with illness and ageing. By happy coincidence, one of these poems falls partly on page 47*.

‘Cassandra Vegas’ is a sequence of six poems in which the title character undergoes major surgery for cancer. Her name signals the poems’ concerns. In Greek myth, Cassandra had the gift of seeing the future, and Vegas is a synonym for gambling: so much language around illness and surgery is about prognosis (prophecy) and percentages (gambling odds). The sequence begins with ‘Casino’, in which Cassandra contemplates the risks of surgery or not-surgery:

to operate will swell the death odds

not to operate makes death certain

This is followed by ‘Theatre’ and ‘Anaesthesia’, whose titles give you their place in the narrative, though not their poetry. In ‘Angel Switch’ she is in intensive care after the operation. In ‘Vegas, Vagus’ she leaves hospital,

the craved bliss of silken air

a leaf's kiss on her bald head

like welcome to a newborn

and learns how to deal with the changes in her body.

The final poem is ‘Ante’, of which all but the first three stanzas are on pages 46–47.

The title, meaning ‘before’, at first seems ironic, as the poem is in the position where you might expect one titled ‘Aftermath’. But it also sits in anticipation of whatever is to come next – an ante is a bet placed on the table before the next hand is dealt.

The first three stanzas have dealt methodically with the immediate past (‘praise from one of the surgeons’), the present (‘each mouthful is a reinvention’) and the unknowable future (‘her chromosomes do not speak / how then can she prophesy?’). The poem now opens out:

she is old in the tooth, the head

the centuries blink, crises grow worse

she has plenty of voice but less reach

she thinks of Apollo's rank kiss

thinks of the woman the god

the half real the half myth

Not that the preceding poems in the sequence have been straightforward narrative, but this marks a shift. ‘She is old in the tooth, the head’ is a simple literal statement, but with ‘the centuries blink’ it takes on a grander meaning. As in Walter Pater’s famous description of the Mona Lisa, ‘She is older than the rocks among which she sits’, the woman in this poem has become archetypal. The crises that grow worse refer both to her individual worsening health crises and to the deepening crises of the society and world around her. In another context, ‘plenty of voice but less reach’ could be a lament about contemporary poetry in general – there’s a lot of it out there, but the readership is small. (I’ve just been listening to a lecture by Sarah Holland-Batt on the Fully Lit podcast, in which she says, ‘Australia has never been short of poets, it’s short only of poetry readers.’)

In the next stanza the archetype is further identified. Cassandra in Greek myth was given the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo, but when she didn’t reciprocate his desire (his ‘rank kiss’), he added the curse that no one would believe her prophecies.

The remaining stanzas enlarge on that last line: what does ‘the half real the half myth’ mean?

The next stanza is a kind of bridge. It first evokes her post-surgery difficulty eating, as described earlier, and then goes to a new place:

the food in her bowl

contracts, congeals, each doubt

a portion, a fragrance, a dance

The unpleasant image of food contracting and congealing becomes a metaphor for doubt – the uncertainty, tentativeness, anxiety that can follow major surgery. Somehow these doubts, this unpleasant food, are transformed, in three steps. The food is a portion – it is what has been allotted to her, what has landed on her plate. Unpleasant as it looks, it has a fragrance – let’s attend to qualities other than its visual qualities. But there’s a subtle shift. Food has a fragrance, but here each doubt is a fragrance. The poem is leaving the literal food behind and talking now about what it represents metaphorically. In the final word of the stanza, the food has gone completely, the doubts are transformed into a dance.

The next three stanzas spell out the nature of that dance:

she visits ocean, gathers beads of it

aqua, turquoise, milky blue

strings them, prays them, swims them

knows nothing, everything, watches

doors, the hours, changes,

stays the same, wonders

Crude paraphrase: ‘She is fully alive to the world.’ I love the idea of gathering beads of ocean – to wear, to pray like a rosary, to immerse herself in them. And I love the line break at the end of this stanza. If the poem finished here, we’d be left with Cassandra filled with wonder. That meaning lingers for a moment, but at the start of the next line the meaning of ‘wonders’ morphs from ‘has a sense of awe’ to ‘asks the following questions’.

stays the same, wonders

if what she guards is herself

or a presence called life

The play with myth is resolved. Like all of us, this woman is an embodiment of something sacred, ‘a presence called life’. ‘Guards’ is an interesting word. Unlike words like ‘battle’ or ‘struggle’ commonly used in this context, it implied strength but also tenderness and caring: she is not defensive, but protective, of the ‘presence’.

And the poem ends with an acknowledgement that survival is inevitably temporary. A harsh paraphrase of the final stanza might be, ‘Wonders how she will die.’ But it’s interesting to notice what that paraphrase leaves out (and I so wish I could read the Chinese translation). In this phrasing she won’t die – she will be killed. The ‘thing’ could be a car, a cancer, a virus, a lightning strike. And what it will kill is this precious, tender thing. It’s not fear of death being expressed, but a cherishing of life, knowing that death will come. The pedant in me would insist that ‘softly’ is an adverb, that it should be ‘bright, soft breath’. I can’t justify it, but the pedant is just wrong this time.

And I’m so glad there’s no full stop at the end. Even punctuation can carry metaphorical meaning.

wonders how it will come

the thing that will kill the bright softly breath

I first read Among the Gone of It while flying between Djagubay land and air and Gadigal Wangal land and air. I wrote the blog post on the Country of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation. I acknowledge Elders past and present of all those Nations, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78. The last poem in Among the Gone of It finishes on page 77, so my personal algorithm sends me to page 47 (I was born in 1947).