William Gibson, The Peripheral (Berkly 2014)

I picked up The Peripheral in a street library soon after I finished reading and blogging about its sequel, Agency, nearly four years ago. Since then, it has been my TBR shelf as a treat for a rainy day. Its time has now come.

There’s a peculiar challenge in writing about it. Possibly the main thing I enjoyed about it is that a lot of the time the reader has no idea what’s actually happening. You’re not even sure what some words mean, or what the characters are not saying. Explanations do come, eventually, but there’s a delicious disorientation as AI devices and other technical marvels multiply, we only half-see crucial incidents, cultural events are described from the point of view of someone who knows a lot more about the background than the reader does. The action takes place in two unspecified future time periods that interpenetrate in often unclear ways. However serious the issues may be – and there’s a plausible version of how the global emergency will develop – there’s a pervasive sense of play. If I summarise the plot, or even the set-up, I’ll be depriving you of that experience.

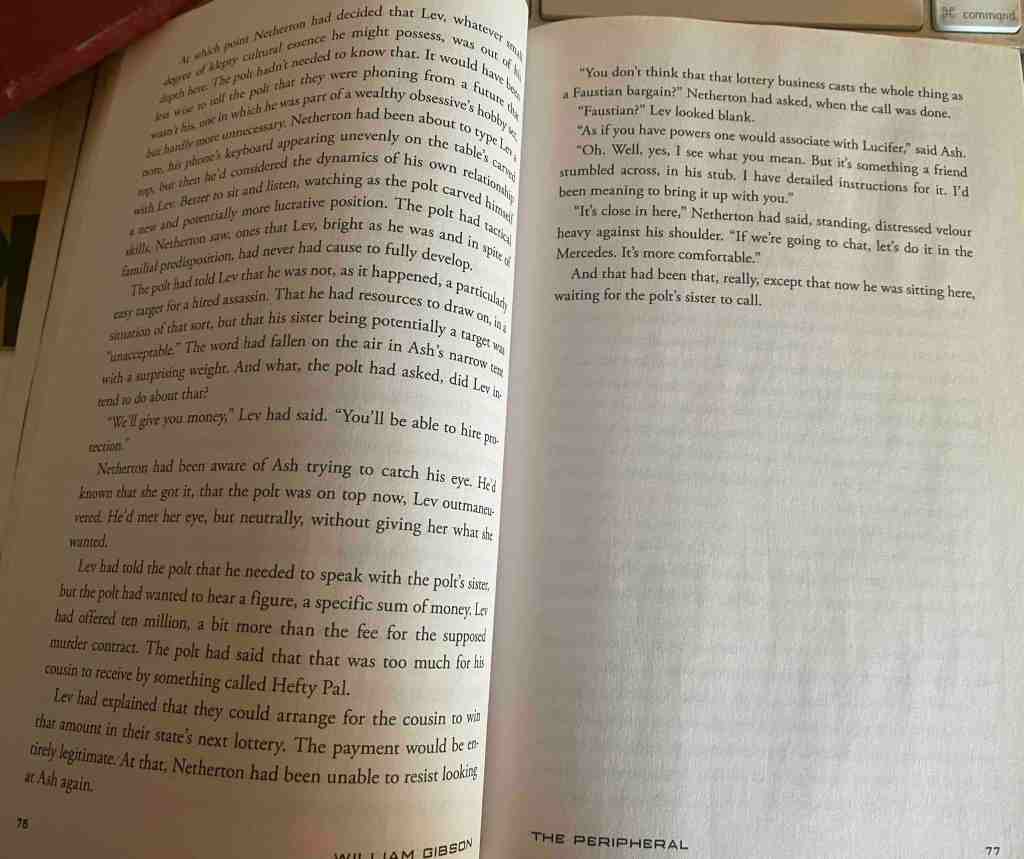

My first idea was to write about first two short chapters – all the chapters are short – but then I thought, oh what the heck, I’ll skip straight to page 77* to give you a taste, and let the spoilers fall where they will.

Lev had told the polt that he needed to speak with the polt’s sister, but the polt had wanted to hear a figure, a specific sum of money. Lev had offered ten million, a bit more than the fee for the supposed murder contract. The polt had said that that was too much for his cousin to receive by something called Hefty Pal.

Lev had explained that they could arrange for the cousin to win that amount in their state’s next lottery. The payment would be entirely legitimate.

Gibson has a gift for coining terms. ‘Cyberspace’ is his invention. Of The Peripheral‘s many coinages, three appear in this short passage: ‘polt’, ‘Hefty Pal’ and ‘stub’. They each have the virtue of suggesting their origins if not their precise meanings. A polt, derived from poltergeist, is a person who is bodily in one place and/or time, but is somehow seeing and acting in another time. (A peripheral is a human-looking artefact, that can be the host to a polt.) Hefty is a mega corporation of which Hefty Pal, as in PayPal, is a subsidiary. A ‘stub’, known more formally as a ‘continuum’, is a key invention of the book, something that readers and half the characters come to understand only gradually. All I’ll say here is that it is something that results from people going back to an earlier time and changing that time’s future.

There are three characters in this scene: Lev, the son of a fabulously wealthy Russian gangster capitalist, whose hobby involves mucking about with the past (stubs/continua are his playthings); Ash, a tech wiz who makes it happen for him (among other distinguishing features, she has tattoos of animals that move around on her skin, often glimpsed running for cover when someone tries to look at them); and Wilf Netterton, put-upon publicist, from whose point of view the story is told in alternate chapters. Page 77 is at the end of a Wilf chapter.

Three more characters are referred to. ‘The polt’ is Burton, a battered veteran in Netterton’s past / our future (though that way of describing things isn’t quite accurate). ‘The polt’s sister’ is Flynne, a gamer in a small US town who is the focus of the non-Wilf chapters. Burton and – on one fateful occasion – Flynne have been employed as polts by Lev under the impression they were testing a computer game. The main narrative is set in motion by Flynne’s witnessing what may be a murder. ‘The cousin’ is Leon, one of their tribe of loyal family members.

At that, Netherton had been unable to resist looking at Ash again.

‘You don’t think that that lottery business casts the whole thing as a Faustian bargain?’ Netherton had asked, when the call was done.

‘Faustian?’ Lev looked blank.

‘As if you have powers one would associate with Lucifer,’ said Ash.

‘Oh. Well, yes, I see what you mean. But it’s something a friend stumbled across, in his stub. I have detailed instructions for it. I’d been meaning to bring it up with you.’

Tiny moments like this give the book its rich texture. There’s the complicity between WIlf and Ash, two underlings who have cultural memories, unlike their rich and powerful employer. (Similarly in the earlier paragraph, it’s fun that Hefty Pal is something in the reader’s future and Flynne’s present that has been forgotten in Wilf’s time.) Like the implied reference to poltergeists, the mention of Faust reminds us that even though the narrative is presented as a tale of high tech, AI and nanotechnology, it often has the feel of demonic possession and fairytale magic. (If you’ve read Gibson’s Sprawl trilogy – Neuromancer (1984), Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) – you’ll remember the prominence there of the legba of Voodoo.)

And that had been that, really, except that now he was sitting there, waiting for the polt’s sister to call

That’s the first hint of the almost-romance that is to almost-blossom between these characters who can only spend time together by means of weird time travel mediated by a peripheral in one direction and an odd little children’s toy in the other.

Now I’m tempted to reread Agency. I remember that it was also gleefully inventive and similarly had two interrelating times. I’m pretty sure that some of the distant future characters are in both books, but my memory is dim. William Gibson is anything but dim.

I wrote this blog post on the unceded land of the Gadigal and Wangal clans of the Eora Nation, not far from where what we now call the Cooks River has been cared for by Elders for many millennia. The weather has just turned cold, but spider webs are still proliferating.

* My blogging practice is to focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently page 77. For The Peripheral, I’ve included a little from page 76 as well.

I came to Bleeding Edge prepared to be baffled and intimidated, as I had been by Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and The Crying of Lot 49 more than three decades ago. W S Gilbert pretty much nailed my response to those books: ‘If this young man expresses himself in terms too deep for me, / Why, what a very singularly deep young man / this deep young man must be!’

I came to Bleeding Edge prepared to be baffled and intimidated, as I had been by Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and The Crying of Lot 49 more than three decades ago. W S Gilbert pretty much nailed my response to those books: ‘If this young man expresses himself in terms too deep for me, / Why, what a very singularly deep young man / this deep young man must be!’