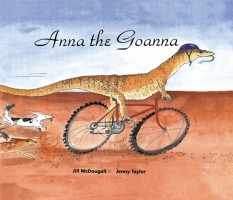

Jill McDougall & Jenny Taylor, Anna the Goanna and other poems (Aboriginal Studies Press 2000)

This is a collection of poems written by a schoolteacher ‘in order to provide classroom reading material which reflected the daily experiences of her students’. That description, taken from Jill McDougall’s bio at the back of this book, could be a recipe for semi-literate, patronising disaster, all the more so when the students in question are Aboriginal. On the contrary, this collection is a delight, words and images both. Not that the opinion of a 65 year old urban middle class white men matters all that much, but I’d be surprised if this book didn’t go down very well indeed, in the classroom and out of it, performed for the students or by them or read in private, by curious non-Indigenous as well as Indigenous children.

Why did I read it? Well, reading the Kevin Gilbert books reminded me of how much I enjoyed his children’s poems, and this was a gift that has been sitting on my shelves for a couple of years now, waiting for a suitable child to turn up to be read to from it. I just decided to stand in for that hypothetical child.

As the title promises, there are silly poems about goannas. There are also mosquitoes, crows, flies, and a crocodile, but it’s not all animals. There are babies, big sisters, football and baseball, a sweet comedy about the difference between Aboriginal and mainstream economics, and two pieces that depart from the general cheerful tone – ‘Too Many Drunks’ and ‘Sad Boys’ , the latter being about petrol sniffing.

Jenny Taylor’s illustrations demonstrate just how important the interplay of text and image can be in a picture book. One page that struck me in particular was ‘Sleep’. The poem:

Goanna like to sleep

In the sandy ground,

In a soft warm hole

Just a little way down.Crows like to sleep

Near the starry sky,

By a big bird’s nest

That’s way up high.I like to sleep

In a cosy bed,

With a blanket for my feet

And a pillow for my head.

The final stanza could be spoken by any child, anywhere. One could easily think of a room with pastel wallpaper and shelves of stuffed toys. The illustration is a revelation about possible meanings for the word ‘cosy’:

I started this more from duty than for pleasure. Previously I’d read just the one short story by Elizabeth Jolley and seen the movie of The Well, and failed to be grabbed. But I want to be well read in Aust Lit, and I couldn’t be sure it wasn’t just sexism that had me avoiding this Big Name Author. It’s a slim book, easy to read on public transport, described by the cover blurb as ‘the novel at the heart of all her work’.

I started this more from duty than for pleasure. Previously I’d read just the one short story by Elizabeth Jolley and seen the movie of The Well, and failed to be grabbed. But I want to be well read in Aust Lit, and I couldn’t be sure it wasn’t just sexism that had me avoiding this Big Name Author. It’s a slim book, easy to read on public transport, described by the cover blurb as ‘the novel at the heart of all her work’.