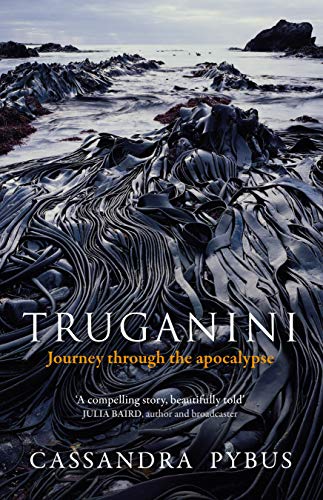

Cassandra Pybus, Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse (Allen & Unwin 2019)

Before the meeting: It was my turn to choose the book. I was tossing up between Truganini, about which I’d heard a terrific podcast from the Sydney Writers’ Festival (here’s a link to my blog post), and See what You Made Me Do, the Stella Prize winner. When I put it to the group there was an overwhelming preference for Truganini’s journey through the apocalypse over Jess Hill’s exploration of abusive men. If we thought this would be less gruelling we were probably wrong.

Truganini is known to non-Indigenous Australian popular history as ‘the last Tasmanian’. That’s rubbish of course. There are still many Indigenous Tasmanians alive and kicking. But Truganini’s life is better documented than any of the survivors of genocide in Tasmania, and she has become, as Cassandra Pybus says in her Preface, ‘an international icon for extinction’. The mythologising began almost as soon as she died, and she has been seen ‘through the prism of colonial imperative: a rueful backward glance at the last tragic victim of an inexorable historical process’. In this book, Pybus sets out ‘to redirect the lens to find the woman behind the myth’.

Pybus’s main historical source is the writings of George Augustus Robinson. To quote the Preface again, ‘Truganini and her companions are only available to us through the gaze of pompous, partisan, acquisitive, self-aggrandising men who controlled and directed the context of what they described’. I’m grateful that Cassandra Pybus did the hard yakka of extracting a story line from such sources, reading them so we don’t have to.

In the 1820s, the Aboriginal clans of south-east Tasmania (Van Diemens Land as it then was, lutruwita before that) were all but wiped out by massacre and disease. Truganini belonged to the Nuenonne clan, whose country included Bruny Island. When George Augustus Robinson, fired by missionary fervour and ambition to be seen as a man of significance, set out to rescue the surviving First Nations people from the violence of the colony, Truganini, her father and some friends accepted his protection and became his guides and later his agents in persuading people from other clans to come under his protection.

For five years the band trudged through forests, over mountains, across streams. Truganini had terribly swollen legs, possibly as a result of syphilis she had contracted from sealers who had abducted her early in life, but she was an adept diver for seafood, and she and the other women in the group were the only ones who could swim, so were often called on to pull rafts across icy rivers. For the most part, Pybus tells the story straight without commenting, for instance, on the moral dilemmas involved in persuading resisting warriors to surrender to Robinson rather than face deadly violence elsewhere, as at the hands of John Batman, who emerges from these pages as a ruthless, brutal slaver.

The result of all these rounding-up missions is that, whatever promises Robinson might have made, people were sent to virtual island prisons, mainly on Flinders Island in the Bass Strait, where the death toll were horrifying. what started out as a ‘friendly mission’ became the coup de grâce of a genocidal program.

After being taken to Port Phillip on the mainland where Robinson hoped they might again play an intermediary role, Truganini and her companions were conclusively dumped by Robinson. He simply turned away from them and never mentioned them in his journals again.

Truganini and her companionos, including a husband and a close woman friend, were settled in Oyster Cover on the east coast of Tasmania, from where they would go on hunting excursions to Bruny Island and elsewhere. One by one, her companions died. With extraordinary restraint, Pybus simply tells us that their deaths were unrecorded. She doesn’t have to spell out the callous disregard of the colonial establishment. Truganini, the sole survivor, spent her last years in the care of John Dandridge and his wife (unnamed) in Hobart. Dandridge would take her across to Bruny Island, so that she could still walk in her own country. To the end, she cared for country, and slept on the floor rather than the coloniser’s bed.

For all the horrors that were inflicted on this extraordinary woman and her people, the one that comes across with most poignancy in this narrative comes right at the end. As people die, the scientific establishment waits like vultures for their skeletons. Graves are dug up, newly dead bodies are decapitated, collections of skulls are sent to England. Truganini expressed her terror at having this done to her own remains, and asked Dandridge to scatter her ashes in the channel between Bruny Island and the main island of Tasmania. But he died before her. Her body was buried, dug up and later exhibited in the Tasmanian Museum – until 1947! After a long legal battle by Tasmanian Aborigines, the museum allowed the skeleton to be cremated, and her ashes were scattered according to her wishes on 30 April 1976, a few days short of the centenary of her death.

And then there are the illustrations. Truganini, her warrior husband Wooredy, the great leader Mannalargenna and others challenge our gaze in portraits painted by Thomas Bock in 1835. There are photographs too, perhaps taken with ethnographic intentions, but when Truganini looks at you from a photo taken by Charles Woolley in 1866 (here’s a link), she isn’t offering herself as an object. At the Sydney Writers’ Festival, Jakelin Troy said, referring to the fact that Truganini walked about Bruny Island in old age:

I’m sure she was making the point that this was still her country and that she’s there, and even if they didn’t think deeply about the fact that it was her family’s country, I think that in reality you can’t avoid that that’s what it is.

It’s hard to look at Truganini in these portraits and not feel that she’s making a similar point: she is still herself, and even if the photographer, the curators, the scientists, the colonial historians don’t think deeply about the fact, she challenges us to acknowledge that she is a human being. As she tells us in a final chapter, Cassandra Pybus has reasons to take that challenge personally: her ancestor received a grant to part of Truganini’s country, and in her childhood she heard stories of the old Aboriginal woman who walked about the family’s property. This book is a powerful, humble and devastating response to the challenge.

After the meeting: We’re still meeting on zoom, probably not for the last time. This book generated a very interesting discussion among us white middle-aged and older men. Some were less enthusiastic about it than others. The negatives first.

One man had studied George Augustus Robinson on the 1980s, particularly the collection of his papers published in 1966, The Friendly Mission. He had approached this book with high hopes, but found that it didn’t add much by way of new perspectives or insights – despite its intention of focusing on Truganini, it largely stayed with Robinson.

Another, who read this just after Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light (my blog post here), was disappointed that neither Truganini nor Robinson, or really any of the other characters, emerged as fully rounded characters. There was precious little exploration of motivations or emotional responses. Maybe, he said, you can’t expect that of history: this might be excellent history but it’s not much chop as literature.

Someone who agreed with that latter point said that the question for him was, if that is so, then how come the book held his attention the whole time, when he usually gave up on history books after 15 pages? Someone said that the subject commands our attention, as this is a story that cuts through to our souls as settler Australians. I think that’s true, but I also think the book is well written, and the failure to flesh out the characters is a strength: Pybus doesn’t speculate or invent, but largely leaves us to join the dots. As someone said, it’s fairly clear that for Truganini and her companions, Robinson’s offer of protection was their best bet for survival.

Challenging the notion that the writing was generally flat and factual, someone read a short passage about Truganini’s father, Manganerer, who had encountered convict mutineers:

These men abducted his wife and sailed away with her to New Zealand, then on to Japan and China. Hastily constructing a sturdy ocean-going canoe, Manganerer had attempted to follow them but had been blown far out into the Southern Ocean. His son had died and he himself was half dead from dehydration when he was found by a whaling ship.

The tragedy was almost too much for this proud man to bear. He had endured the murder of his first wife and the abduction of his two older daughters by the intruders, and now they had taken his second wife. His only son was dead and his remaining daughter had abandoned him for the whaling station. His distress was compounded when he discovered that in his absence almost all of his clan had succumbed to disease, as had all but one of the people visiting from Port Davey, who were under his protection.

There was a moment’s silence on the zoom space. With such a litany of horrors – and this is early in the book, the worst devastation comes towards the end – there’s not a lot of need for further authorial commentary.

One man took up the cudgels on Robinson’s behalf. He said he felt protective of him. Yes, he took on the role of ‘Protector of Aborigines’ out of a kind of opportunism, and yes, his ventures finished off the ‘extirpation’ that the notorious Black Line failed to achieve. But he had a huge inner struggle. At some level he recognised and respected the humanity and the cultural strength of the people in his care (there are scenes in the book where he eats and sings and dances with them). But he was blinded by his belief system and could only at rare moments acknowledge what he was actually doing. And – I think I’m quoting correctly – isn’t that blindness something that we all have?

I don’t think it’s much of an exaggeration that the book had us staring into the abyss of our nation’s foundation story. Today, someone is offering to send us all bumper stickers in support of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Truganini is the 14th book I’ve read for the 2020 Australian Women Writers Challenge.

I am a fan of anything written by Cassandra Pybus. Five years ago on a visit to Tassie (exactly five years ago one month back) to catch up with an elderly German uncle (whose mother died in Auschwitz-Birkenau) I wanted to visit Oyster Cove. I collected him from his home in Lindisfarne and back across the bridge and through Hobart and south we went – to the Kettering ferry (across to nearby Bruny Island). After a morning tea I asked where Oyster Cove was located. I doubt it took more than five minutes to reach the place. I parked the car. The sign at the gate explained that this was Putalina (Oyster Cove) that it was now a Palawa education centre/land rights held. It was a cold overcast day. We walked in the direction of the water – noting buildings to our right – a camping/education place. In the distance – a figure stood by a fire – smoke lazily curling up – a dog alongside. It was a woman. As we approached I introduced myself and my uncle – expressing my reverence for this tranquil site – not to misunderstand the historical significance and terrors held by the 19th-century people who lived out their lives here after the Flinders Island “experiment”. The woman was a teacher of Palawa kani – the amalgam of surviving Tasmanian languages – in local primary schools. After some more pleasantries – my uncle and I made our way back to the car. It’s hard to know what to say at such moments – more a time for personal reflection. Cassandra Pybus wrote about early Black American-born convicts in New South Wales. in her book Black Founders (2006) she devoted a chapter to family connection Billy BLUE (born late 1730s Jamaica, Queens county – just to be sure you don’t think Caribbean – the same as Donald Trump’s birthplace/childhood). I don’t feel any admiration for Robinson – he had no heart. That is clear even from a simple reading of history. On Kangaroo Island in 2018 I uncovered the story of other Tasmanian women who had ended up there – descendants still in existence. Thanks for this review Jonathan.

LikeLike

I have this book, and I must admit I wondered whether (like your friend) I would learn much from it given that I’ve already read a fair bit about Tasmanian Aborigines and Robinson…

I keep hoping that there might one day be some Tasmanian Indigenous fiction that tells these stories in an engaging way. I remember being surprised to learn about the Black Line in Rowan Wilson’s The Roving Party, and then realising that I had already read about it. It took the power of a well-crafted novel to make that fact come alive for me.

LikeLike

I always love your reading group posts Jonathan. I loved your comment that “If we thought this would be less gruelling we were probably wrong”. I don’t know. I haven’t read Pybus, but I have read about 40% of Jess Hill – it’s my kindle book on my iPad so I read it when I’m out and about waiting for appointments etc. It is very gruelling – the case studies are something else. But, it is a book everyone should read I think, even those who “think” they’ve read it all. Her research and analysis is impressive. It was put forward for my reading group but several didn’t want to read something so gruelling!!

Anyhow, I enjoyed your reporting on your discussion about character development. I agree with the person who suggested that you don’t necessarily expect character development in history or biography. For me, when you discuss a book, one of the first principles is “what is its form” and “what are the expectations of that form”? Sounds like you did discuss that a bit.

LikeLike

My partner is making her way through Jess Hill’s book. She has read me bits, so I know what you mean when you say everyone should read it, and it’s on my list. But aforesaid partner keeps having long breaks between chapters …

I guess we did discuss the question of form, though not with the clarity of your comment.

LikeLike

Yes, I am too.

And yes it sounds to me like you did even if you didn’t specifically know you were but that makes it more real, more organic, in a way. Do any of your reading group friends read your reports?

LikeLike

One friend has been reading it for some time. It’s not that I was being secretive but I never mentioned the blog in the group. I was outed just last when when someone who thought he might be expected to write a report on the meeting for the benefit of the ones who couldn’t come sent out a WhatsApp message to say that people should just read my blog post about it. I do worry about overstepping boundaries – ‘What Happens in Book Group Stays in Book Group’ is a reasonable principle, I think – but so far no one has objected to anything I’ve written.

LikeLike

Pingback: History Memoir and Biography Round Up: September 2020 | Australian Women Writers Challenge Blog