Kristen Lang, Earth Dwellers (Giramondo 2021)

I started reading Earth Dwellers when coming up for air during the horror stories of Jess Hill’s See What You Made Me Do. and then again during those in Colum McCann’s Apeirogon. Each of those books included its own relief from the horrors – one by cool-headed analytic journalism, the other by an intriguing structure and a seemingly inexhaustible capacity for digression – but I can’t begin to tell you what a relief Kristen Lang’s poetry was, what balm for the soul, right from the dedication:

For the wombats and the slime moulds ... And for all who work to protect the entanglement, the networks of lives, billions of years in the making, by which the earth is more than stone.

These poems take us away from the troubled world of humans harming humans to intense, specific, tactile engagement with the non-human world. They take us to the tops of mountains, in Kristen Lang’s home state Tasmania and in the Himalayas; they take us on bush walks and visits to the ocean; to caves and the stars. They deal with the sublime and the intimate, sometimes in the same brief poem. They grieve and rage for the damage being inflicted on the planet by human activity, but always with a deep love and respect for this world. In these poems, the non-human world isn’t there as a metaphor or a mood indicator: there’s a consistently humble attempt to be present, to be aware of being part of it all: ‘We were never alone’ is how she puts it in ‘Wading with horseshoe crabs’.

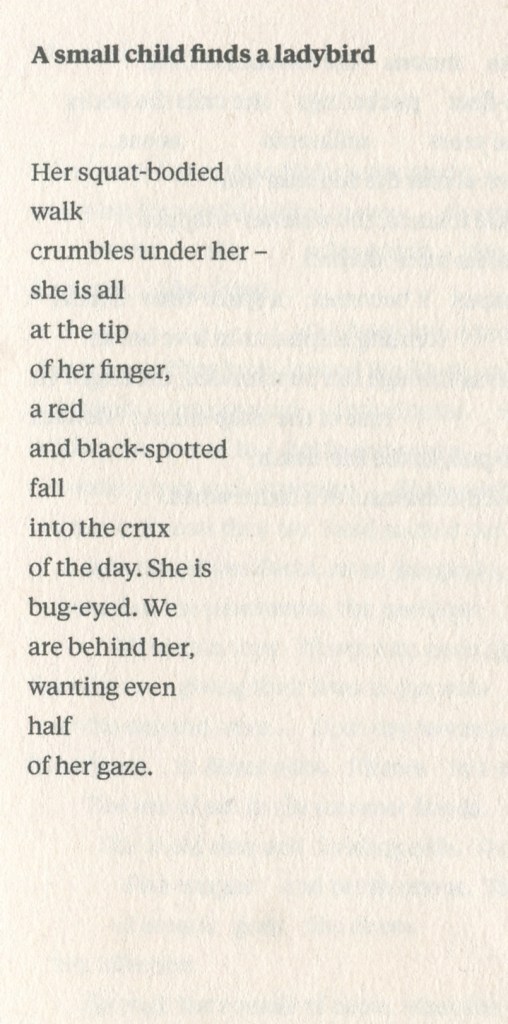

As usual, I want to talk about just one poem. I’m picking ‘A small child finds a ladybird’:

This poem must surely strike a chord with anyone who has spent attentive time with a small child. Certainly I’ve been privy to many moments like this one, and felt a similar appreciative, possibly envious, awe at the intensity of a child’s gaze.

‘A small child finds a ladybird’ may be the only poem in this collection that focuses on a human character. Other poems have people in them, but they are companions to the speaker, neither addressed nor looked at directly, experiencing, observing, and being part of the natural world along with her. Here, it’s as if the poem’s speaker takes a step back, to observe the person experiencing, observing and being part of something.

The title of the poem sets up a strong mental image. A web image search on “small child ladybug” (‘-bug’ rather than ‘-bird’ in deference to US cultural dominance) gets you a cartload of cuteness, much of it cloying. That might be attractive to some readers but, for me and probably you, it establishes a central challenge for the poem: how to put words to that image that don’t regurgitate the pre-digested cutesyness. You might say that that’s a version of the central challenge for any poem, something to do with T S Eliot’s ‘tradition and the individual talent’, and I wouldn’t argue. This one meets the challenge like this in its opening lines:

Her squat-bodied walk crumbles under her –

Three things snag my attention: the words ‘squat-bodied’ and ‘crumbles’, and the way ‘walk’ has a line to itself. each of these things is sightly jarring, but if you hover over them you discover how well they communicate: the shape of a toddler, the kind of attention a toddler brings to the act of walking, and what happens when that attention goes elsewhere. It’s the walk that crumbles, not the child herself. This poem observes the child with the same precision that other poems in the book observe a platypus or floating filaments of gum blossom. If the reader wants to go down the cuteness path, the poem won’t stop them, but nor does it require them to go there.

In the next nine lines, the child is absorbed in the ladybird. She doesn’t simply have it on her fingertip. She is ‘all’ there with it. She hasn’t just stumbled when she sees the insect, she has taken on its qualities: the fall is red/ and black-spotted’. The way ‘fall’ has a line to itself, and gets extra emphasis from its rhyme with ‘all’ in line 4, prepares us for that interesting word ‘crux’ – as in crucial. This crumbled walk, this fall, hasn’t been an accident: it’s as if the rest of the day has been moving towards this crucial moment, and will emanate from it. ‘Bug-eyed’ takes on a richer meaning in this context: not just wide-eyed, but with eyes filled with the fascinating bug.

And then there’s ‘We’ – the poem’s speaker and us, the readers. We’re behind her, at a distance from the ladybird. And the last three lines are the second reason I wanted to write about this poem: it’s a kind of ars poetica. The wish expressed here, to have

________ even half of her gaze

is what Kristen Lang’s poems in general strive for. I know that as a reader I sometimes (often?) miss the metaphorical dimensions of poetry. So when someone writes that the world is grey in the moonlight, I take them at their word and have to be told if they’re talking about a terrible betrayal. But I don’t think I’m missing that kind of thing in these poems. In these poems, a mountain is a mountain, an iceberg an iceberg, a ladybird a ladybird. And there’s something profound in that

Earth Dwellers is the fifth book I’ve read for the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2021. I’m grateful to Giramondo for my copy.

I’m in the middle of a Louise Crisp collection atm, which is my first time with an ecopoet. Lang was my second choice when I was browsing the poetry section. But very happy with the Crisp, esp since returning from a drive through some of the country she writes about (Monaro & Gippsland).

I know I’ve said this before, but I really like how you deep-dive into just one poem; I always learn some thing new. This time ars poetica.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Brona. Ecopoet is a word I was groping for ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Non-Fiction (General) Round Up: April 2021 | Australian Women Writers Challenge Blog

Pingback: Journal Blitz 10 | Me fail? I fly!

Pingback: Jonathan Shaw, None of us alone (#BookReview) | Whispering Gums