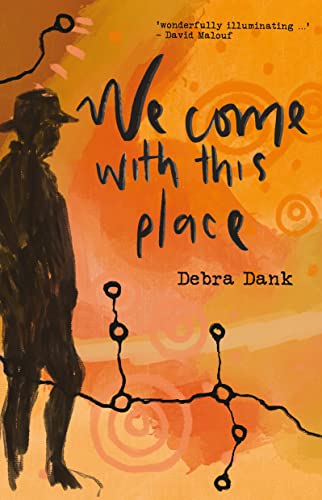

Debra Dank, We Come with This Place (Echo Publishing 2022)

Before the meeting: We Come With This Place won an amazing four prizes at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards this year, including Book of the Year: you can read the judges’ comments here and here. They include this:

This sensational memoir is an unheralded reflection on what it is to be First Nations in Australia, and on the very deepest meanings of family and belonging.

In one of her modest acceptance speeches at the awards ceremony, Debra Dank mentioned that the book started out as part of her PhD study. In the Preface, she elaborates:

I wanted to show how story works in my community and how it has contributed to our living with country for so long. It seemed to me imperative to talk about those voices, both human and non-human, who guided Gudanji for centuries before anyone else stepped onto this land.

(page viii)

The weeks after the referendum on the Voice failed seemed a perfect time to read this book. The Uluṟu Statement from the Heart’s call for Voice, Truth, Treaty has been rejected at the political level: it’s a relief to listen to the voices of First Nations writers like Debra Dank, and participate in this form of truth-telling.

It’s a terrific book: an intimate portrait of family life, placed in the context of ancestral stories, a deep sense of connection to Country, and resilience in the face of the horrors of colonialism. The family lived ‘under the Act’ in Queensland, and managed ingeniously to hide little Debra when the Welfare came looking for light-skinned children; her father worked on a number of rural properties, where sometimes he was treated with great respect, other times not so much. She helps her father work on a windmill. There is a tactfully written scene where she stands up against family violence, and magical moments with her grandfather, and with her children and grandchildren. I love the pages where Dank’s white surfie husband (he’s saltwater, she’s dust) struggles to learn how to read the bush, to see the things that are glaringly obvious to his Aboriginal children.

Dank identifies as belonging to dry country, and she makes brilliant use of images of dust. On the very first page, ‘vague images try to speak to [her] through dust motes rising from the thick pale pages’ of a 400-year-old edition of a book by Aristotle, and a few pages later, she tells us that the stories of her people – the Gudanji kujiga – ‘grow from the fine dirt that plays around your feet and makes the dust that rolls over the the vast Gudanji and Wakaja country’. As a child she is fascinated by the way a drop of blood from a foot caught on barbed wire blends into the soil. Dust rises from the heels of a family group in the not so distant past running in terror from armed men on horseback. It memorably obliterates the Country-scarring road in the passage I versified the other day (here).

I don’t want to give the impression that the book is written in high metaphorical mode. Here’s a little passage from page 76 (for those who came in late, I like to have a closer look at that page because it’s my age). The family are driving from one place of employment to another, and appropriately enough the page starts with dust:

The wind brought dust in with it, but it was the Dry and the road wasn’t too bad. The caravan happily kicked up dust into frothing red feathers that followed us for a bit, then settled back onto the road. Long stalks of tall yellow grass formed a guard of honour as we traveled across the plains. We played games of spot the turkey and several times tried desperately to convince Dad to stop for the goannas that would run across the road and then lie still and flat in the shelter of the yellow grass and amber shadows, but we needed to get there so he didn’t stop. Besides, Mum said she refused to turn up at the new station with a dead gonna in the car.

You see what I mean: if you’re not alert to the dust motif, those frothing red feathers that follow and settle are a nice piece of decoration; if you’ve picked up on it, they’re a reassuring presence of Country. And this tiny moment embodies the way the family manages to live successfully in two worlds: goannas would be great, but not when you’re about to meet a new white boss.

After the meeting: It was our end-of-year meeting, so as well as discussing the book, we exchanged gifts – of books chosen from our bookshelves. I gave Diana Athill’s wonderful memoir, Somewhere Towards the End, and scored J M Coetzee’s 1986 novel, Foe. We also, in a three-year tradition, each brought a poem to read to the group: poems represented included Seamus Heaney, Oodgeroo Noonuccal writing as Kath Walker, Adrian Wiggins, J Drew Lanham, Rosda Hayes, and Sean Hughes.

There were seven of us. Two hadn’t read the book – it’s a busy time of year. One was ‘at about 55 percent’ on his device. One said he had read seven other books since so had difficulty recalling it with any clarity. We were in a pub rather than our usual domestic setting. None of that stopped the conversation from delving into the book, ranging widely and then finding its way back to the page. Those of us who had read it celebrated the way it presented the history from inside an First Nations point of view: even Kim Scott’s brilliant novel That Deadman Dance didn’t get to the inside story as completely as this; and it has a calm assurance that, say, Julie Janson’s Benevolence lacks, for all its other strengths (the second of these comparison came up in conversation in the car ride home).

One Covid-ed absentee emailed in some cogent comments – noting that there seemed to be a number of voices, and that the passages dealing with the author’s personal experience worked better than the narration of ancient stories. He loved, and others agreed, the bits of bushcraft such as reading shadows and catching fish with your hands in the desert, the cultural landscape connections.

I went on a bit about dust.

There was a lot of reflection on personal experiences the book reminded people of. There was also, as usual, much excellent conversation about unrelated matters, including Anna Funder’s Wifedom; the recent blockade in Newcastle and a similar one nearly 20 years ago which provoked a very different response from the police and the press; philosophy and poetry groups in a small town; behind the scenes stories from a fascinating film project; travellers’ tales.

And that’s a wrap for the Book Group for 2023.