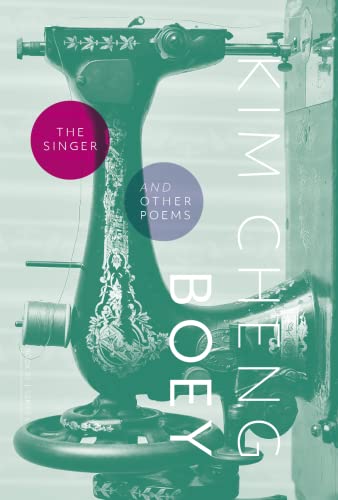

Kim Cheng Boey, The Singer (Cordite Press 2022)

There’s so much to love in this book.

I was inclined to love it sight unseen. I’ve been delighted by Kim Cheng Boey’s readings in past years when the Sydney Writers’ Festival had room for local poets. He co-edited (with Michelle Cahill and Adam Aitken) the excellent 2013 anthology, Contemporary Asian Australian Poets. He has written insightful reviews of one of my favourite poets, Eileen Chong, and had a walk-on role in one of her poems. This is the first of his books that I have read.

When I got my copy direct from Cordite Press – I tried at least three bookshops – I loved it for the cover alone. You expect the title The Singer to refer to the poet, perhaps in an attention-seeking way, but then you tilt the book and see the cover image clearly: it’s a Singer sewing machine. (My mother didn’t call her labour-saving devices the washing machine, the vacuum cleaner or the sewing machine, but the Hoover, the Electrolux and the Singer.) It’s a brilliant title: yes, poetry is like song, but it’s also craft.

And page by page, I kept on falling in love. There’s a Preface in which Kim Cheng writes of the different ‘weight’ of his poetry-making over time:

When I was younger, poetry carried me posthaste, high on the fuel of experience and freshness of thought, from initial impulse to final form. In middle age the roles are reversed – I am the mule, the porter, learning the weight and heft of the poem so I can carry it long-distance – over months and often years.

‘Perhaps,’ he continues, ‘the change occurred the moment I became a migrant.’ He migrated to Australia from his native Singapore in his early 30s, in 1997. Since then he has continued to take part in Singapore’s literary and cultural life as well as that of his adopted home. The book’s three parts can be read as tracing this geographical movement over time. The first, ‘Little India Dreaming’, has five long prose poems full of the smells and sights and sounds of a remembered Singapore childhood, including the title poem. Here’s a small extract to give you a feel for it:

You almost pray to the Singer, its dark cast-iron hull, to

carry your mother's song. You pray for the treadle to

stir, for the finished dress to be unstitched, its seams

unpicked so the dress can materialise again from the

chalk outline. You take the birthday outfit out of the

wardrobe of forgetting and become the five-year-old

wearing your mother's love.

The second section, ‘The Middle Distance’, is introduced with a quote from Louis Mac Neice, ‘This middle stretch / Of life is bad for poets.’ Each of its five poems is set in places other than Asia or Australia., and it’s tempting to see an unsettled, midlife quality to them.

The seven poems of the third section, ‘Sydney Dreaming’ – to simplify appallingly – lay claim to Australia as a place that can be called home.

My arbitrary blogging practice of looking at page 76 has once again given me a gift. That page occurs near the end of the book, in ‘Sydney Dreaming’, the title poem of the third section.

I love this poem (I know I’m using that word a lot, but it can’t be helped). In it the speaker walks around inner suburbs of Sydney, haunted by the tales and memories of other cities and ghosts of Sydney past. If it was terrible, banal rubbish, I might still have loved it because I have walked every step that the poem follows. I too lament the disappearance of second-hand book shops in Pitt Street. I know the painted up man with the didgeridoo in the Central tunnel, as well as the old Chinese man ‘scraping a dirge on his erdu’. Chinatown, Broadway, Glebe Point Road, Gleebooks, all lovingly named and recognisable. Then Darlinghurst Road, the wall, the Holocaust Museum, Macleay Street. The poem made me want to go for a long walk.

And it’s a terrific poem. Here are a couple of stanzas from page 76 – the walk down to Woolloomooloo from Kings Cross:

You follow the bend and the view opens to the ivory cusps

of the Opera House and the dark arch of the bridge over the silver-glazed

azure scroll of the harbour, the sky burnished gold in the last exhalations of the sun.

Soon the flying fox formations will rise from hangars of Moreton Bay figs

in the Botanic Garden, and weave arabesques around the halo

of the spanning arches of the Coathanger. You remember seeing this even

before you arrived, memory in the image, image in memory,

the sky and the harbour dyed incarnadine in the first postcard

you ever received from a childhood friend settled in a new life

Notice that it’s in the second person: ‘You follow the bend.’ The poem’s speaker isn’t just telling the reader about a walk he has taken, he is inviting us to walk with him – which is especially effective for readers who have in fact walked in those places. The long lines have a leisurely, strolling feel: no hurry, no need to reach any rhyming points or keep to any metric timetable. The conversational tone and language creates a companionable feel.

Then the register shifts, as the poem enters its final movement.

You follow the bend and the language opens to ‘ivory cusps’ and ‘silver-glazed azure’ and ‘burnished gold’ and ‘exhalations of the sun’. That’s such a Sydney moment – any Sydneysider arriving at Circular Quay train station will have had their phone-absorption interrupted by the exclamations of tourists seeing the Bridge–Harbour–Opera House scene for the first time. Rounding that bend in Woolloomooloo has a similar breathtaking effect, and the language responds.

Then two things happen. First, the speaker asserts that he belongs here by looking forward in time: he knows that the flying foxes will soon fill the sky and enjoys anticipating the spectacle (still with the elevated language, ‘arabesques’ and ‘spanning arches’). Second, he knows that he hasn’t always belonged, and memory asserts itself. He had seen this sight in a postcard long before seeing the actual thing. I’m reminded of those passages in Proust about how the reality inevitably falls short of the anticipated image. That’s not how it is here, but there’s a strange unreality nonetheless – ‘memory in the image, image in memory’ – the present moment is a palimpsest. The whole poem revolves around that interplay of past, present, anticipated future and imagination. The whole walk is experienced as a palimpsest.

I’m restraining myself from quoting the lines that come next, because it’s getting close to the poem’s stunning conclusion, and even with poetry spoilers are an issue. Enough to say that the Bridge is transformed effortlessly from that spectacular postcard image to a terrific metaphor for the poet’s status in the midst of an ever-changing life of exile, belonging, and longing.

As a footnote: the title ‘Sydney Dreaming’ might be a worry. I don’t read it as claiming any of the First Nations meaning of the word ‘Dreaming’. In the course of his walk, the poet-flâneur passes a number of First Nations people: the man in the Central tunnel, and a real or imagined group of dancers in Woolloomooloo. The latter are mentioned after the speaker has been lost ‘in a dream of home, almost’: his dream is definitely lower case, and carefully distinct from that other, deeper, ancestral Dreaming.

The Singer won the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry earlier this year (click here for the judges’ comments). Maybe it’s so hard to find in the bookshops because it sells out as soon as it hits the shelves. I hope so. Anyhow, especially but not only if you live in Sydney or are part of a Chinese diaspora, see if you can get hold of it. Did I mention that I love it?