Claudia Rankine, Plot (Grove Press 2001)

Claudia Rankine’s two most recent books, Citizen: An American Lyric (2014) and Just Us: An American Conversation (2021) – links are to my reviews – issued brilliant, multi-faceted, take-no-prisoners challenges to anti-Black racism in the USA, shedding light and warmth on the issue well beyond American borders, and enthusing readers, me included, well beyond the borders of Contemporary Poetry land.

When a friend lent me Plot as part of a Covid care package (the Covid turned out to be a non-event, thanks for asking – vaccines and antivirals work wonders), I looked forward to more of the same. That is to say, I came to this slim volume of poetry, published more than a decade before Citizen, with completely inappropriate expectations.

The first page of verse gives fair warning. It consists of just four lines:

Submerged deeper than appetite

she bit into a freakish anatomy. the hard plastic of filiation.

a fetus dream. once severed. reattached. the baby femur

not fork-tender though flesh. the baby face now anchored.

OK, this book is going to expect the reader to work. A string of phrases separated by full stops without any opening capitals and only one conventional sentence. There seems to be something about biting onto the flesh of a foetus. It’s a dream, and maybe the dislocated syntax represents the fragmentary nature of the dream. But why ‘freakish’? What is ‘deeper than appetite’? What has been severed and reattached, and how? My phone dictionary wasn’t a lot of help with ‘filiation’ – the most relevant implied definition is ‘the process of attachment’ – but why plastic? And so on.

These four lines announce the book’s central theme of pregnancy, and they foreshadow that for much of it a good part of the reader’s pleasure is in being lost in a cloud of probabilities, not quite knowing what the endlessly suggestive words mean.

There is a story. Liv, an artist, is pregnant and ambivalent about it. The foetus has a name, Ersatz. The father’s name is Erland. The book’s most accessible moments are in occasional snatches of dialogue between the adults – in which Erland usually fails to grasp Liv’s emotional tumult. Most of the rest enacts that tumult: ‘dreams, memories, and meditations expanding and exploding the emotive capabilities of language and form’ (that’s from the back cover).

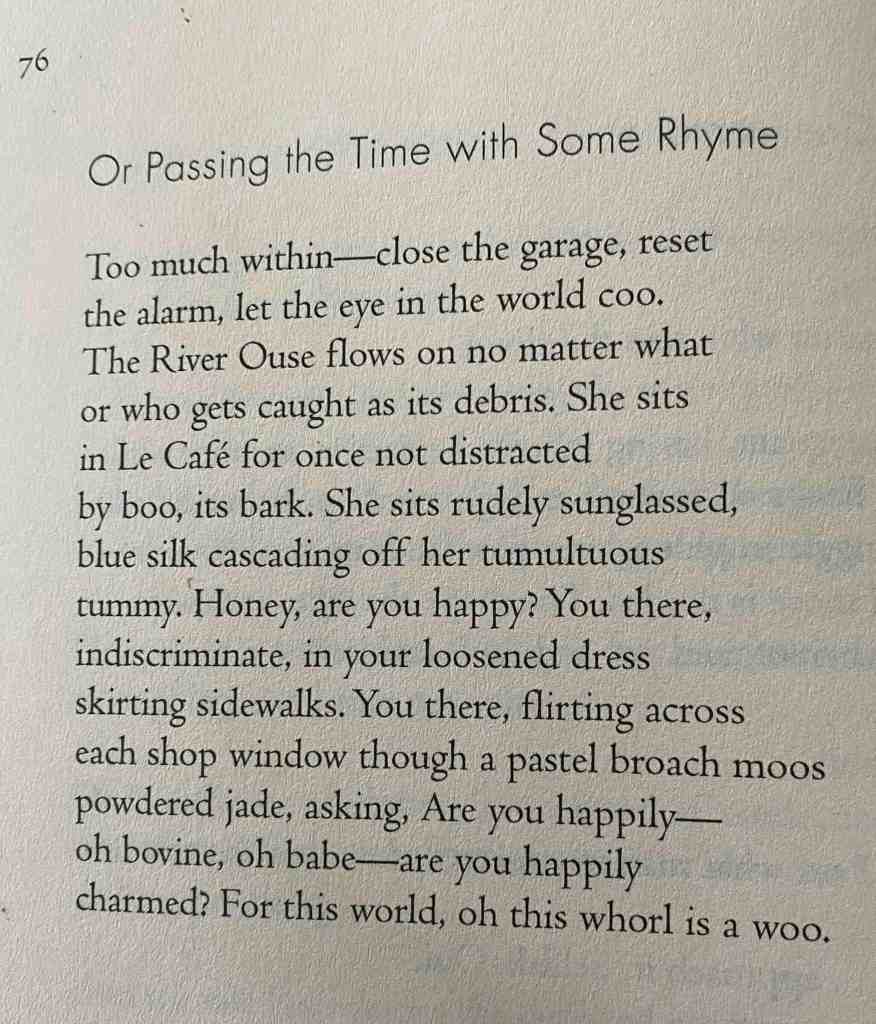

My blog practice is to write about page 76. In the kind of coincidence that I’ve almost come to expect, the only poem from this book that I could find online was the one on that page, ‘Or Passing the Time with Some Rhyme’, quoted in a review by Kate Kellaway in the Guardian. Kellaway doesn’t say a lot about this poem, but her review sheds excellent light on the book as a whole: for example, she describes many of the poems as ‘painterly’, and reminds us that Liv and Erland are the first names of the actors in Igmar Bergman’s monumental movie Scenes from a Marriage.

Page 76 (right click to enlarge):

There are lots of possibilities, but here goes with my reading.

This poem is something of a turning point in the book, as signalled by the ‘Or’ in its title (not ‘On’ as a careless reading might see). We can keep going as we have been, the title says, or we can take a different route. Let’s loosen up and just pass the time. Instead of more of the serious, introspective prose poems, let’s have some fun with rhyme.

Or Passing the Time with Some Rhyme

The body of the poem fills that promise, though perhaps not obviously.

To understand the first four lines, you need to know that in an earlier sequence, Liv has worked on a painting entitled Beached Debris referring to Virginia Woolf’s death in the River Ouse. Her brooding on Woolf’s suicide reflects her dark emotions about her pregnancy.

Too much within – close the garage, reset

the alarm, let the eye in the world coo.

The River Ouse flows on no matter what

or who gets caught in its debris.

The voice here is not, as mostly so far, giving us Liv’s inner workings. It’s more like a bossy friend: ‘Too much introspection, snap out of it.’ Maybe Liv has been painting in the garage. It’s time to close it, reset the burglar alarm and leave the house. Undo the fixation with Virginia Woolf’s death and notice the wider world, the river that still flows on no matter what tragedies it has seen.

The next lines are no longer addressed to Liv, but show her from the outside for the first time in the book. She’s looking cool, even arrogant, and splendidly, exuberantly pregnant:

or who gets caught in its debris. She sits

in Le Café for once not distracted

by boo, its bark. She sits rudely sunglassed,

blue silk cascading off her tumultuous

tummy.

This is a good time to notice that the poem is a sonnet, the only one in the book, and as far as I can tell the only poem in a traditional form. (Back to the ‘Or’ in the title: we could keep on with prose poems or we could have a crack at a sonnet.) It doesn’t have an obvious rhyme scheme (I’ll come back to that), but it does have the classic sonnet turn, right here in line eight where it’s supposed to be. The poem now addresses Liv again:

tummy. Honey, are you happy?

You can read this a number of ways. It could be a straightforwardly sympathetic request for information. It could be a niggle: you look OK, ‘for once not distracted’, but are you actually happy? Or, and this is the reading that carries most weight for me, it could be registering unexpected good news: ‘Honey, after all this misery, are you actually happy?’

The remaining six lines (the sestet of the sonnet) have a cinematic feel. Liv is on the move, and the questioner repeats the question (this is very Boomer of me, but I think of Lynn Redgrave in the opening scenes of Georgy Girl, with Judith Durham on the soundtrack asking her questions in song). The tone still arguably ambiguous, but now with the possibility of enchantment much stronger:

tummy. Honey, are you happy? You there,

indiscriminate, in your loosened dress

skirting sidewalks. You there, flirting across

each shop window though a pastel broach moos

powdered jade, asking, Are you happily –

oh bovine, oh babe – are you happily

charmed? For this world, oh this whorl is a woo.

In ‘oh bovine, oh babe’, one of the words commonly used to disparage pregnant women is being reclaimed – someone might see her as cow like, but she is indiscriminately flirty, window shopping, and to all appearance happily charmed. It’s still a question, but surely now leaning towards a positive answer.

But what about rhyme? And also, what about those words that don’t make obvious sense that I’ve blithely glossed over until now?

After spending some time with this poem I realise that I have to let go of my habitual prosaic way of reading, and almost sing this, accentuating the vowels, starting with the title:

Or Passing the TIME with Some RHYME

When I do that, something wonderful happens. The sound patterning, especially the internal rhyming, is at the heart of how the poem works. Just look at all those oo words: Too, coo, Ouse, who, boo, rudely, blue, you (several times), loosened, moos, woo. There’s more to the soundscape than this (‘tumultuous tummy’, for example, and heaps of alliteration in the sestet), but once you’re alert to how the poem sounds, those odd words – coo, boo, moo and woo – make sense. It’s easy enough to find a paraphrasable meaning for them: ‘let the eye in the world coo’ equals ‘let the world look on you with the indulgence of a lover who bills and coos’; ‘not distracted / by boo, its bark’ equals ‘not having one’s attention dominated by this thing that is scary like a ghost or a savage dog’; ‘this world is a woo’ equals ‘this world is waiting to be loved by you, is wooing you’. It almost feels as if the notion of bovineness is introduced so the brooch (I think ‘broach’ must be a typo) in the shop window could moo. The literal meaning matters, but maybe what matters even mnore is the way the words just sing on the page. The final phrase, ‘oh this world is a woo’, becomes a fabulous, semi-nonsensical affirmation of life as joyful.

PS: Now have another look at the four lines I quoted at the start of this blog post. Read it emphasising the sounds, especially all those Fs. Quibbling at it for clear meaning seems much less valid all of a sudden. The pleasure is real.

Thanks Jonathan ! Id hoped by lending you this book you’d help me with a way into it . Reading out loud ! What a pleasure it is . Understanding is still some way off but it’s nice to get a foothold. Makes me recall the pleasure of sounds in the Grey Bees .

LikeLiked by 1 person