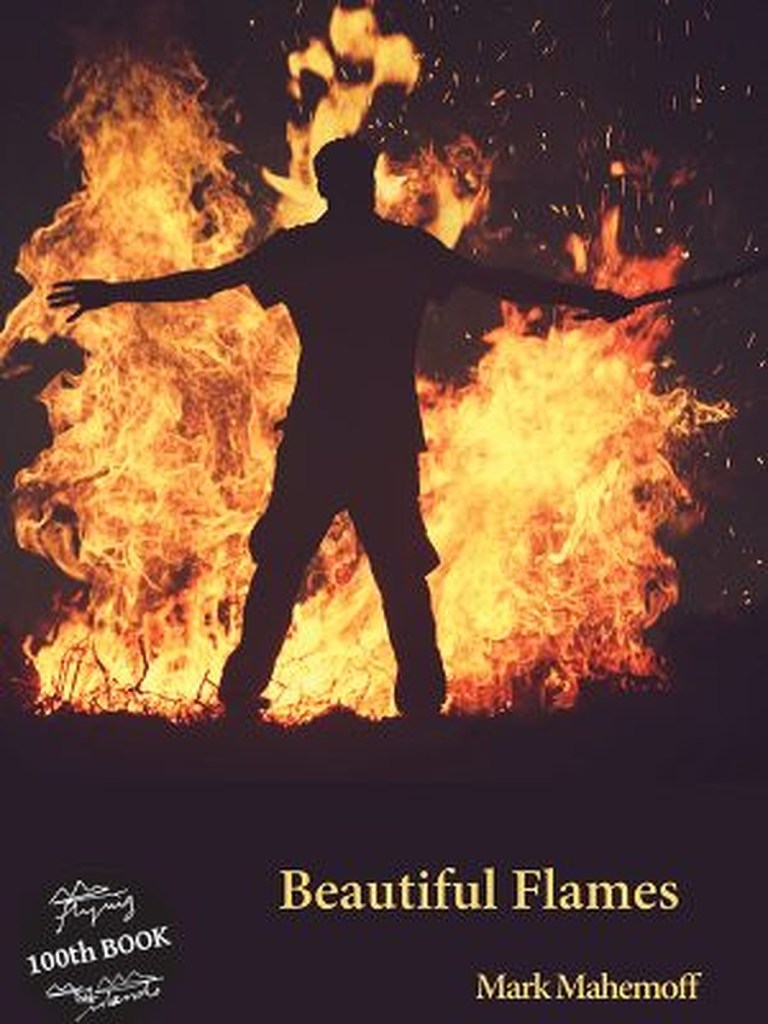

Mark Mahemoff, Beautiful Flames (Flying Island Books 2024)

This is another pocket-sized book I took with me on my recent trip to North Queensland. It’s Mark Mahemoff’s sixth book, a modest, user-friendly poetry collection in four sections.

The first section, ‘Chronicles’, mostly includes brief stories taken from life – family events, losses, a school reunion, the process of leaving home. From ‘Leaving’ (page 20):

Because childhood is a country

no one escapes unscathed

we haul it like a suitcase

stuffed full of unwashed clothes.

The second section, ‘Observations’ is what it says on the lid, observations on life’s passing parade. The titles of its poems generally tell you what to expect: ‘Kookaburras’, ‘Night Train’, ‘A Mediation’, ‘Bar Sport’, ‘Professional Development’.

The main pleasure of these first two sections is like what can get from a photograph of something ordinary – not claiming that it’s anything other than ordinary, but inviting us to pay attention to it for a moment. I generally try not to quote the final lines of poems – it’s too much like revealing the punchline of a joke – but the last stanza of ‘Nasturtiums’ (page 53) is too good an example of what I mean. Having described the large patch of these flowers on a lawn ‘somewhere in Haberfield’, and wondered whether they count as ‘weeds, food or flours’, the poem concludes:

But just devour them with your eyes

and you'll find that's enough

when you're walking beside someone

or alone

in sunlight.

That might seem banal but there’s some subtle, even self-effacing complexity. Mahemoff isn’t just talking about his own walk, but gently and elliptically inviting us to go on a walk of our own, to see for ourselves, and the last two line breaks create an unsettling effect. (What if it’s an overcast day, will it be enough then? If not, is it because the flowers look drab without the sun on them? Or is the sunlight a kind of companion?) The poem isn’t tied off in a neat bow.

The third section, ‘Travelogue’, comprises six poems in the form of notes from visits to, respectively, Western Australia, New Zealand, Melbourne, two unnamed places (one of which has a river and the other cactus plants), and Texas. The last-mentioned (‘Dallas in January’, page 84) forms a nice companion piece to Andrew O’Hagan’s essay ‘The American Dream of Lee Harvey Oswald’ in The Atlantic Ocean, which I read a couple of weeks ago: O’Hagan and Mahemoff describe the same museum, and have similar responses.

Page 77* contains two of the nine short poems that make up ‘New Zealand Snaps’.

The first is ‘Lower Shotover’:

Lower Shotover

Cool in the shade.

Singeing in the sun.

'The ozone layer is thinner here,'

she said.

You watch washing flap

while jets cruise past mountains.

How does one manage

this surfeit of beauty?

A bee falters

from flower to flower.

I had to look Lower Shotover up, but even without seeing images online (here are some if you’re interested), I knew from the poem the kind of place it is. And that’s without any of the kind of writing you might find in a tourist brochure or a poem that trusted its readers less.

It’s a thing in some contemporary poetry to plonk one thing down after another – an image, a quote, an aphorism – and call on readers to make their own connections. The poem becomes a collaboration between writer and reader. ‘Lower Shotover’ does a version of that, giving us a two-line observation about the temperature, a snippet of dialogue, images of washing on a line and jets in the sky, an abstract question, an image of a bee. We’re not left entirely to our own devices. We know from the title that the disparate items all refer to a place, but it’s up to us, for example, to imagine who speaks the third line (I think it’s the host at a tourism spot, but you might think it’s a visiting climate scientist), or whose washing flaps in the fifth line. But what is definitely there is the way the poem moves from bodily sensations in the first lines, to human connection in the third and fourth, to attention first to things seen and heard in close-up and then things seen and heard heard far-off . Only then, in the seventh and eight lines, is there an oblique reference to the reason the poem exists: the beauty of the place. But instead of trying to describe the beauty, the poem in effect confesses itself inadequate to the task. The image of the bee in the last two lines brings a nice meta touch – the poem itself has been faltering from one thing to another.

The second poem, unlike most of the poems in this book has a strict form. Each of its stanzas consists of 17 syllables – 5 in the first and third lines and 7 in the middle line. Yes, they are haiku, as we have come to understand that form in the English-speaking world.

Fox Glacier

Mountains demand awe.

We whisper in their presence,

take snapshots, and leave.

It rains ceaselessly.

A single set of headlights

burns through the distance.

Haiku, like sonnets, have a turn. In these examples, the turn has a visual quality: in the first, our gaze rotates (literally turns!) from the mountains to the tourists; in the second, there’s a change of focus from wide to narrow. I’m not sure that the rules of haiku, strictly speaking, allow words like ‘I’ and ‘we’, but the point of this ‘we’ here is that the human presence is tiny, and temporary, barely there at all.

Having written that, I have just read in Mark Mahemoff’s bio at the back of the book that his poetry

is chiefly concerned with framing, reimagining and memorialising commonplace moments, primarily in an urban setting.

Which makes me notice one more thing about these haiku: the Fox Glacier is about as far from an ‘urban setting’ as you can get, yet both haiku have industrial elements – snapshots and headlights – that make their (momentarily puny) demands on our attention.

I finished writing this blog post on Gadigal Wangal country, where I’ve noticed leaf-curling spiders waiting patiently in their rain-spangled webs. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this land.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently 77.

Would you happen to be the Jonathan Shaw who tutored in Australian Literature at Sydney University in 1971? If so, I owe you a lifelong debt of gratitude – I was one of the students in one of your tutorial groups. – Van Ikin

LikeLike

Hi Van. I am indeed him. I’m surprised that you remember me – I did follow your career for a time as you became a power in the world of SF/F and lost sight of you. I’enjoyed my time tutoring, and I’m glad you remember it as useful.

LikeLike