Ali Cobby Eckermann, She Is the Earth: a verse novel (Magabala Books 2023)

Ali Cobby Eckermann is a Yankunytjatjara woman. Her mother and grandmother were taken from their families when very young as part of the government policy. She herself was also taken. Raised by a loving German-heritage family, she found her way back to her First Nations family as an adult, after years of searching.

I first met her poetry in Black Inc’s Best Australian Poems 2009, edited by the late Bob Adamson. In his introduction, Adamson said of her wonderful dramatic monologue ‘Intervention Pay Back’ that it made ‘a new shift in what a poem might say or be’. You can read it in the Cordite Review at this link. Two poems by her, also dramatic monologues, were included in the special Australian issue of the Chicago-based Poetry journal in May 2016. They can be read on the Poetry Foundation website: ‘Black Deaths in Custody’ here and ‘Thunder Raining Poison’ (on the effects of the Maralinga atomic tests on traditional APY lands ) here.

I haven’t read her memoir, Too Afraid to Cry (Ilura Press 2013), or her first verse novel, His Father’s Eyes (OUP 2011). But I can tell you that her second verse novel, Ruby Moonlight (Magabala Books 2012), which deals with the aftermath of massacre, is brilliant (my blog post here). Of her verse I have read the chapbook Kami (Vagabond Books 2010) and Inside My Mother (Giramondo 2015, my blog post here), which are both filled with the intensities of re-uniting with her Yankunytjatjara kin and culture, and the loss of her birth mother soon after finding her.

All of this work has enormous power, and has garnered many awards in Australia and elsewhere.

She Is the Earth, which arrived eight years after her previous book, is a different kind of writing.

It’s described on the title page as a verse novel. There are no characters apart from an unnamed narrator, and no clear events apart from her meandering through an Australian landscape. Any movement is internal. But the book is meant to be read as a single text rather than a collection of short, untitled poems.

At first, I thought it was an imagined story of pre-birth existence, in which the narrator moves towards being born, taking on substance in the world. But that didn’t seem to work and in the end, I gave up on trying to find a narrative, and just went with the flow.

The flow is far from terrible, and the language is never less than gripping, but I don’t know what to say about the book as a whole. I can refer you to better minds than mine.

Here is part of what the judges had to say when the book won the Indigenous Writers’ Prize at the 2024 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards (go to this link for their full comments):

Ali Cobby Eckermann writes in a poetics of self-emergence in which the spectral is made solid through an eloquent economy of language and lifeforms. Each word of this verse novel is deeply considered and rich with meaning, forming as a whole a narrative which is sometimes gentle and sometimes sharp, both beautiful and terrible, and always profound in its exploration of healing, hope and the earth. Each word reads as a gift to the reader.

I recommend Aidan Coleman’s review in The Conversation (at this link). He discusses the book as an example of minimalism, and says interesting things about its recurring images, and even about the developing narrative:

The speaker in these poems is both child and mother, pupil and teacher. References to children and motherhood abound. Initial images of disconnection, anxiety and trauma give way, in later sections, to wholeness and calm.

But the journey is not linear: hope is present from the earliest sections and trauma haunts the closing pages. Healing is presented as an ongoing process that is projected beyond the poem.

[Added later in response to Kim’s comment: Kim on reading Matters had a very different, and more attuned response than mine. You can read her blog post at this link.

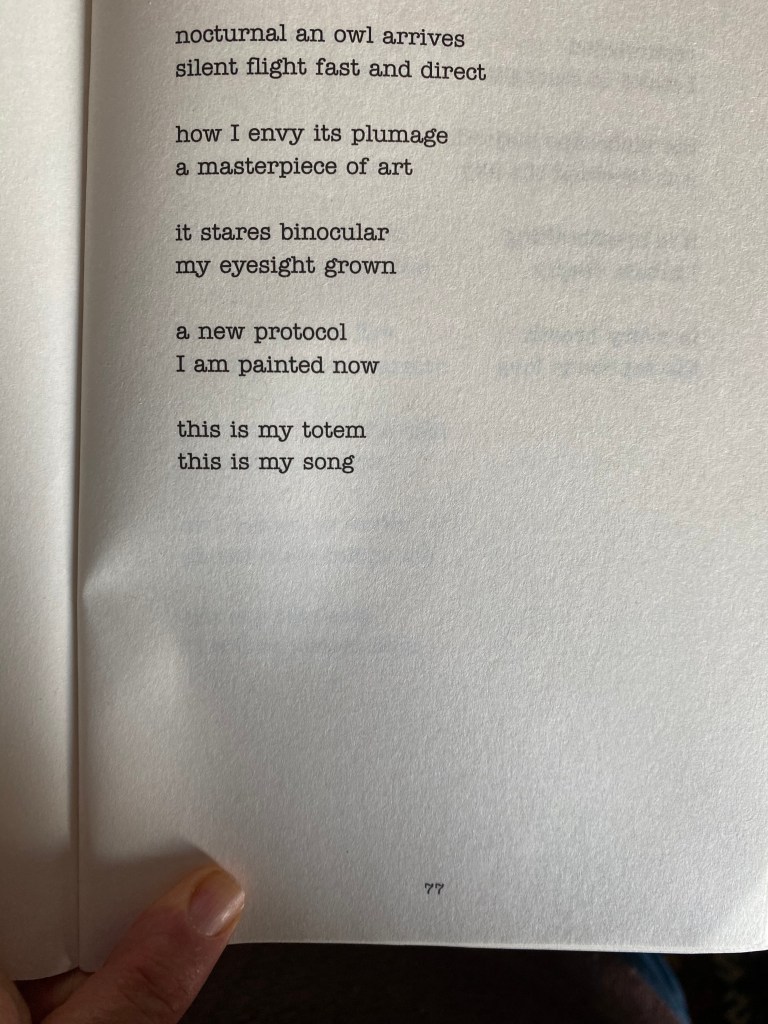

Page 77* occurs toward the end – there are 90 pages in the book. Piggybacking on Aidan Coleman’s reading, I can see it as a moment of consolidation, of identity firming up in the landscape:

The pleasure of these lines doesn’t depend on their function in the broader narrative. The owl arrives; the narrator admires it; their eyes meet, and there is a moment of identification with the bird; the ‘masterpiece of art’ of the bird’s plumage somehow transfers so that the narrator is painted. The final couplet pulls all that together.

In the wider scheme, that last couplet resolves more than the preceding eight lines. Up to now, the narrator has been full of yearning and unease. Here she seems to find peace:

this is my totem

this is my song

‘Totem’ takes the hint of identification in the comparison of eyes a step further. There’s something about finding a place of belonging, of deep affinity, of being at home in the world. Once that’s found, there’s the possibility of singing, of having one’s own song.

The first word on the next page is ‘resurrected’, and a couple of pages further on my favourite lines in the book:

I am a solo candle

inside a chandelier

this is the wisdom

I need to succeed.

I still can’t say I understand what’s going on at any given moment in this book. But maybe that’s OK.

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country, where it is my great joy to live. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this land.

* My blogging practice, especially with books of poetry, is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 77.

Pingback: 2024 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards shortlists | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog

Thanks for liking to me, Lisa

LikeLike

I read this earlier in the year when it was longlisted for the Stella Prize. I described it as “a luminous love letter to Mother Nature, including her life-sustaining ecosystems, weather patterns and landscapes” and loved the recurring /repeated motifs. I do think there was a part early on about birth (and the violence of it) so we are agreed about that aspect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I’ve clearly got a blind spot with this book. Maybe I’ll come back to it in a year and it will speak to me. I’ll add a link to your post

LikeLike

Thanks for the link back to mine. I wasn’t expecting that. Nor do I think my views are more attuned than yours. I think the beauty of this particular work is that it is open to interpretation and your thoughts are no less valid than mine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmm. I guess by ‘attuned’ I meant it worked for you, and it just didn’t for me. It happens, maybe especially with poetry

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks Jonathan; I will request the book from my library; the quoted lines blaze 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person