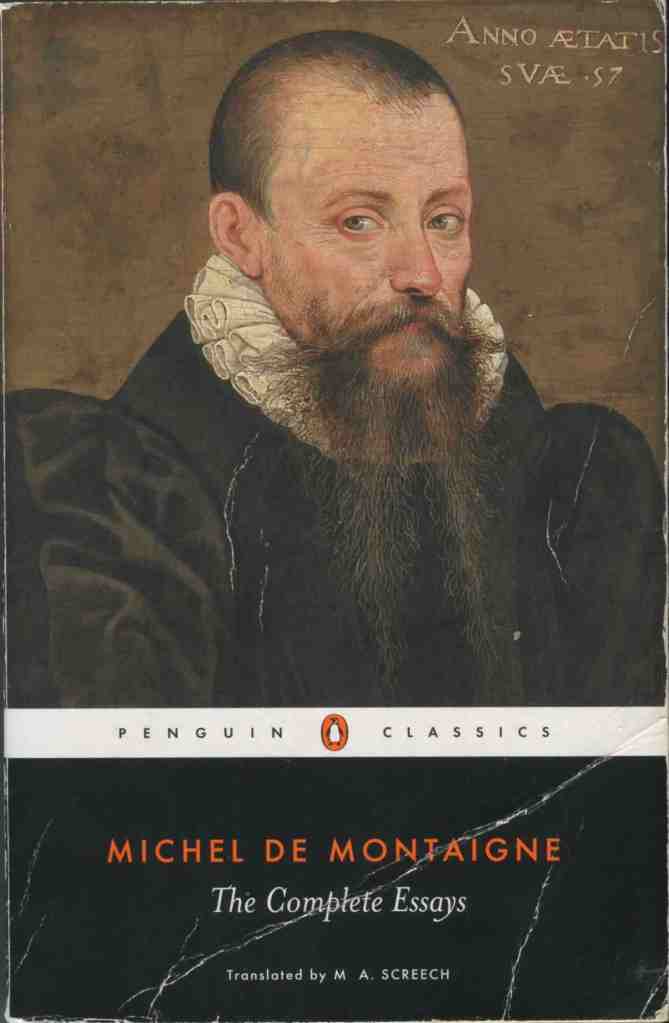

Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays (Penguin Classics 1991, translated by M. A. Screech)

– part way through Book 2, essay 17, ‘On presumption’ to part way through ‘On the resemblance of children to their fathers’

These aren’t so much progress reports as monthly snapshots from my reading of Montaigne’s Essays four or five pages a day. Last month I was part way though ‘On presumption’ and enjoying his unflattering self-portrait. That essay became even more fabulously self-deprecatory, including this (on page 730):

As for music, either vocal (for which my voice is quite unsuited) or instrumental, nobody could ever teach me anything. At dancing, tennis and wrestling I have never been able to acquire more than a slight, vulgar skill; and at swimming, fencing, vaulting and jumping, no skill at all. My hand is so clumsy that I cannot even read my own writing, so that I prefer to write things over again rather than to give myself the trouble of disentangling my scribbles. And my reading aloud is hardly better: I can feel myself boring my audience. That apart, I am quite a good scholar! I can never fold up a letter neatly, never sharpen a pen, never carve passably at table, nor put harness on horse, nor bear a hawk properly nor release it, nor address hounds, birds or horses.

Last month I snuck a look into the future and predicted that this month I would be writing about ‘Three good wives’. Fortunately I don’t have to spend time on that essay, as its version of a good wife is one who will kill herself when her husband dies. Did I mention that some of Montaigne’s views and attitudes can be pretty repulsive? The essay after that, ‘On the most excellent of men’, is hardly less repulsive: his three excellent men are Homer, Alexander the Great and Epaminondas, and in all three cases, including Homer, he seems to regard military skills as the main criterion for excellence. He also seems to take Alexander the Great’s PR at face value. (I shudder to think that essayists a thousand years from now will speak of Donald Trump as the greatest president ever.)

Today, however, I have started on the final essay of Book II, ‘On the resemblance of children to their fathers’, which is surely one of those that have endeared Montaigne to readers for nearly 500 years

Typically, the proclaimed subject of the essay is nowhere in sight in the first couple of pages. Instead, he reflects on the nature of his work and on changes that have happened in his life over the eight years he has been writing essays.

I think it’s true that Montaigne invented the essay form, and these paragraphs give a charming insight into how he went about it.

All the various pieces of this faggot are being bundled together on the understanding that I am only to set my hand to it in my own home and when I am oppressed by too lax an idleness. So it was assembled at intervals and at different periods, since I sometimes have occasion to be away from home for months on end. Moreover I never correct my first thoughts by second ones – well, except perhaps for the odd word, but to vary it, not to remove it. I want to show my humours as they develop, revealing each element as it is born. I could wish that I had begun earlier, especially tracing the progress of changes in me.

It’s probably that spontaneity and the possible vulnerability that goes with it, that makes the essays so alive even all these years later. Maybe I should be less judgemental about essays like the one on good wives – he may have thought differently on the subject on another day.

But that’s enough about the work. He needs to tell us about his health:

Since I began I have aged by some seven or eight years – not without some fresh gain, for those years have generously introduced me to colic paroxysms. Long commerce and acquaintance with the years rarely proceed without some such benefit I could wish that, of all those gifts which the years store up for those who haunt them, they could have chosen a present more acceptable to me, for they could not have given me anything that since childhood I have held in greater horror.

I’m roughly 30 years older than Montaigne was when he wrote that. Though I’m in reasonably good health, I recognise his impulse to tell the world about his bodily ills. As I turn the page, he moves on to one of his recurring topics: when it makes sense to kill oneself (see essay on good wives etcetera). Happily, he is leaning towards staying alive:

After about eighteen months in this distasteful state, I have already learnt how to get used to it. I have made a compact with the colical style of life; I can find sources of hope and consolation in it.

That’s a good thing for his readers, as there was a whole third book to come.

This blog post was written on Gadigal-Wangal land, where understandings of the universe beyond Montaigne’s imaginings were developed millennia before the Ancients he so loves. I acknowledge the Elders past, present and emerging of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation.

You bring him alive, JS – self-obsessed – but no more or less than most of us who like to read and think and write – for ourselves – and for others… I appreciate these tidbits, these insights into a fellow human-being separated by four+ centuries. Jim

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jim. I think it isn’t so much that he was self-obsessed as realising that the one thing he knew best was himself, so though he is steeped in the writers of antiquity and endlessly interested in philosophy, he keeps coming back to his own experience and attempts to be as unadornedly truthful as he can – even while quite sure about the human propensity for self-deception.

It turns out that the page after the one I was quoting from reveals that what he calls colic is actually extremely painful – to do with passing stones! – and he has very interesting things to say about the possibility of giving voice to the pain without departing from the stoic ideal of accepting it.

LikeLike